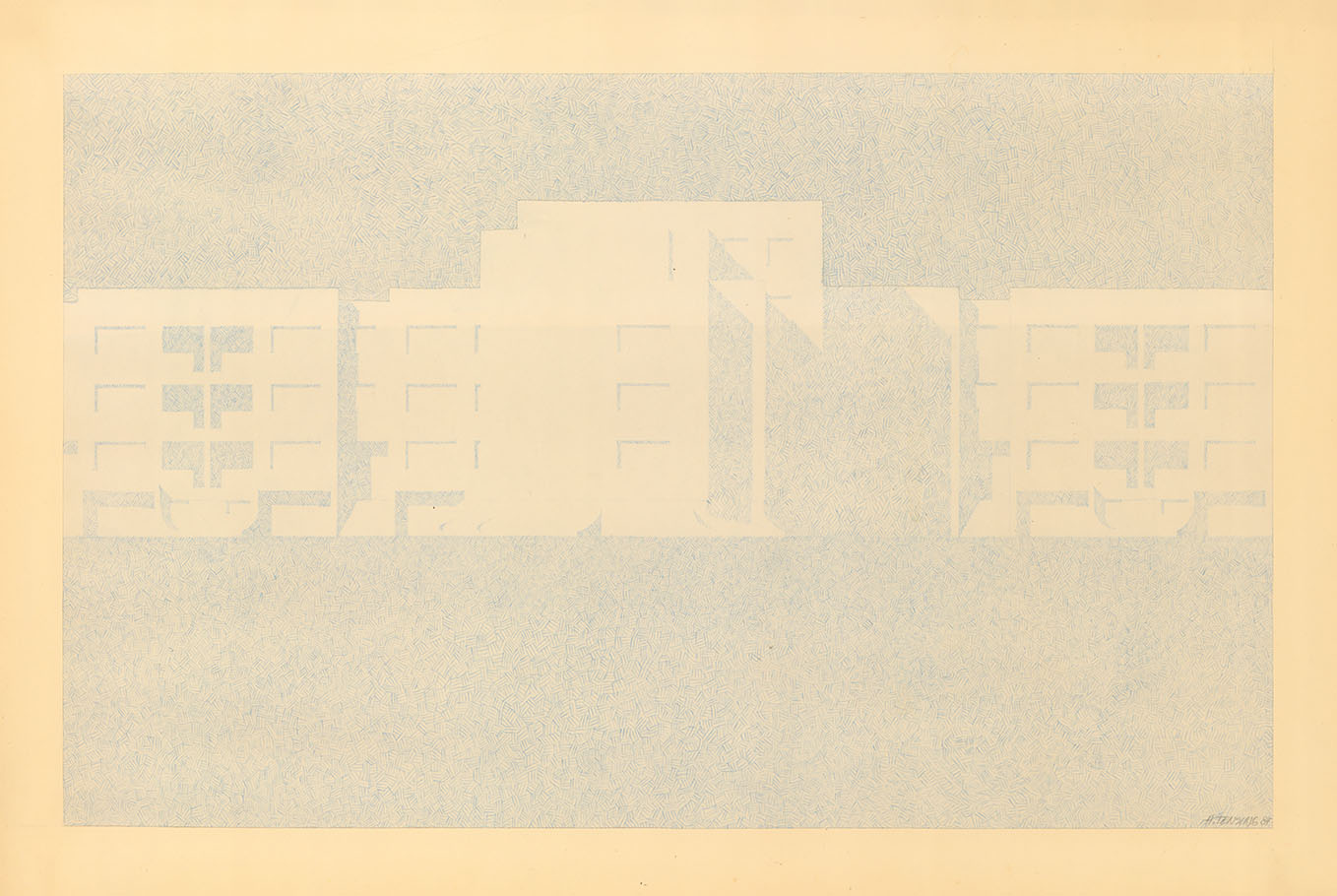

That Blue Rain

Anli Tensing, 1984. EAM 5.9.2

The delicate minimalist drawing was completed for the architectural exhibition at the Tallinn Matkamaja (hiking house, currently named as Hopner House) in 1985. The work was awarded the prize of the ESSR Ministry of Culture for “poeticised depiction of new districts”. The exhibition itself was a landmark of its time. For the first time, architects were able to show their free creative work alongside their building projects and planning schemes in a exhibition – they could submit architectural drawings, fantasy projects, graphics, models, architectural designs (see Arhitektuurikroonika ’85. Tallinn “Valgus” 1987). Several works from the exhibition at the time belong to the museum’s collection, as well the exhibition’s guest book. Anli Tensing’s (Tummi, 1957-2006) prize-winning work, together with a few dozen other works, unfortunately ended up in an attic of an Old Town building, where it was found in 2022. Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1980ndad, architect: Anli Tensing

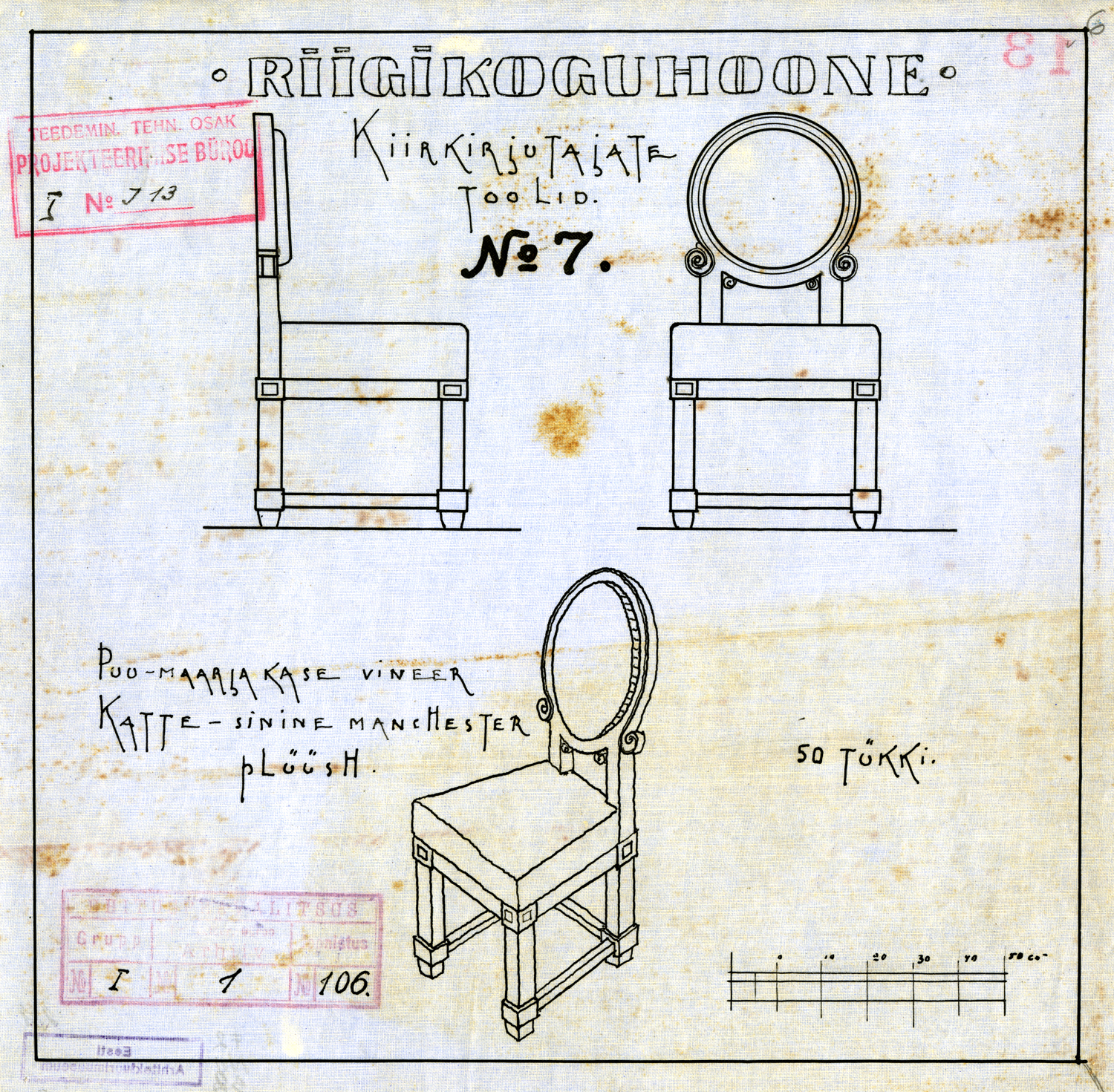

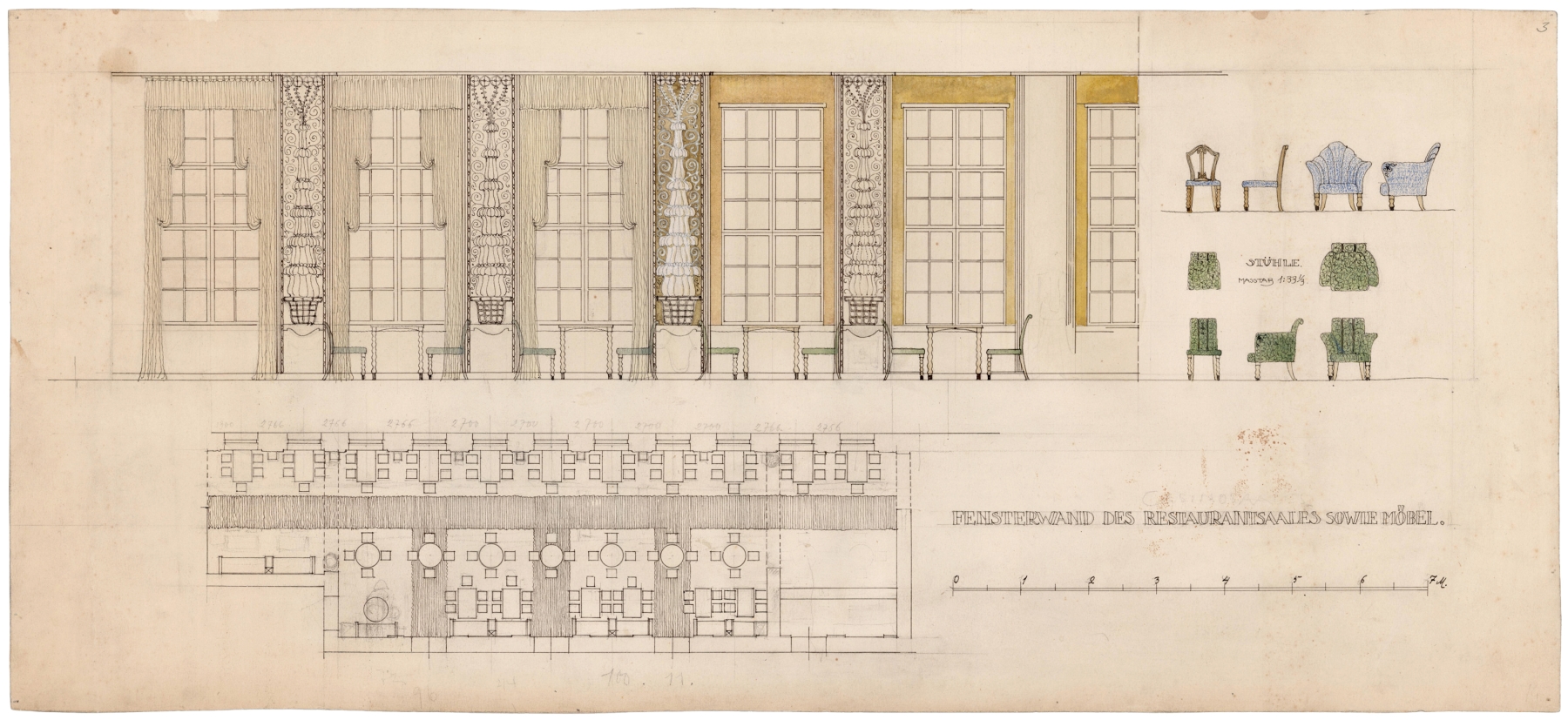

The furniture designs of the Parliament building

Herbert Johanson, 1920-1922. EAM 2.11.8

In 1922, the most important state building of the newly independent Republic of Estonia – the new modern Parliament building (architects Herbert Johanson, Eugen Habermann 1920-1922) – is completed in Toompea. “It is a simple, yet self-conscious and distinctive building, which gracefully combines the individual sense of design of the authors and the fit with its medieval surroundings, while remaining modern.” This is how art critic Hanno Kompus characterised the Parliament building in his introduction to the book “20 Years of Building in Estonia: 1918-1938 “. Herbert Johanson’s designs were also used to create the unique furniture of the Parliament building, which repeats the geometric shapes of the building’s interiors and the Art Deco zigzag motif. The furniture was produced by the Luther factory, for whom it was the first major public commission (see Jüri Kermik. A. M. Luther 1877-1940. Innovation of form from material. Tallinn, 2002). The high quality of Lutermas’ work is demonstrated by the fact that most of the 100-year-old furniture is still in use today.

The museum has more than 30 furniture designs for the Parliament building, ranging from the podium in the sitting room to the coat racks. The original drawings come from the archives of the former Ministry of Roads and were transferred to the museum in 1992. Text: Anne Lass

(klick on the picture to see more)

Veel: 1920s, architect: Herbert Johanson

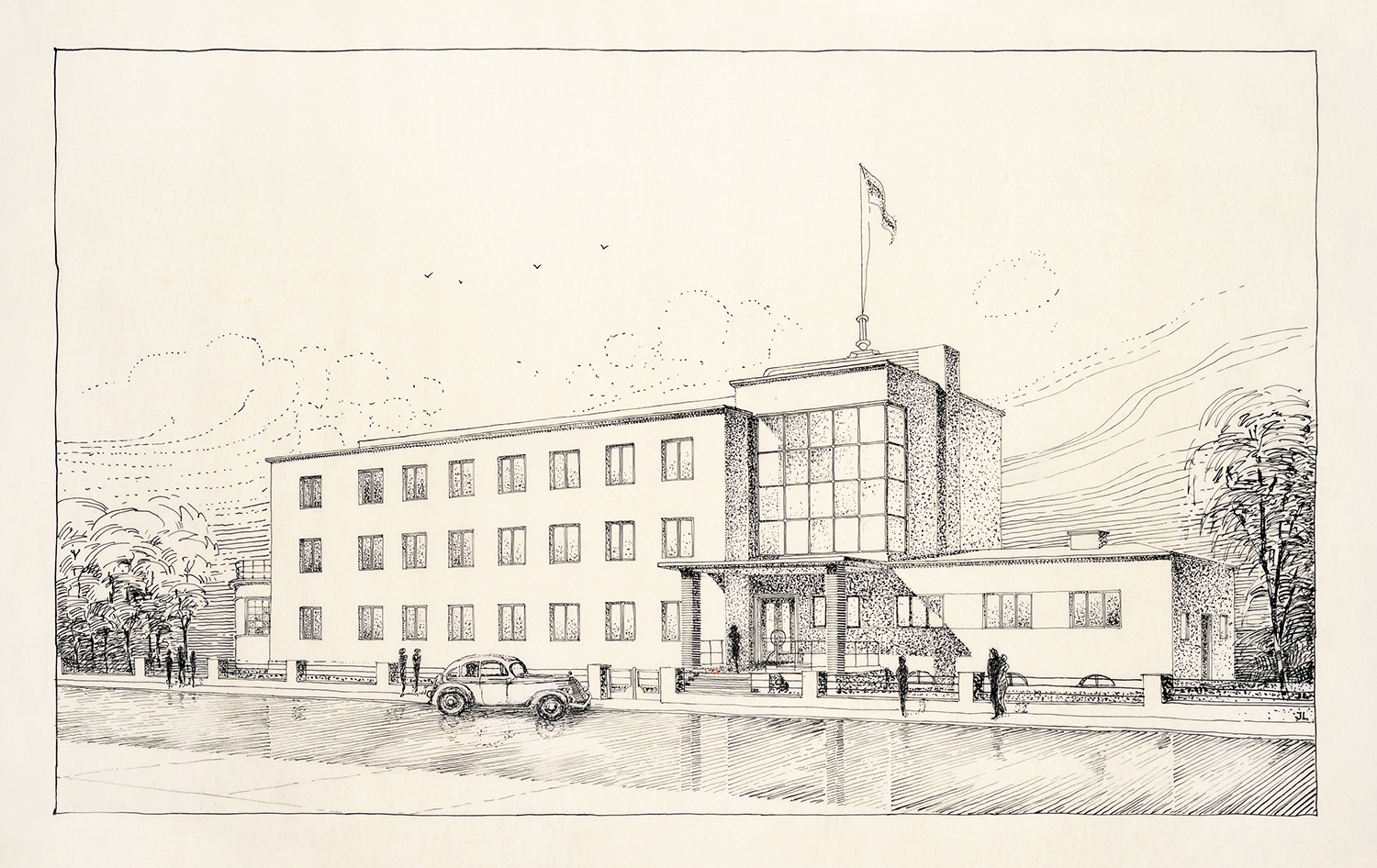

Sanatorium named after General J. Laidoner in Haapsalu

August Volberg, 1936. EAM 31.1.13

The Estonian Red Cross sanatorium in Haapsalu, named after General Johan Laidoner, was designed by architect August Volberg. The building was completed in 1937. Built primarily for soldiers who had suffered in the War of Independence, the sanatorium had 41 double rooms and a spacious terrace with a sea view. The main architectural emphasis of the functionalist building is on the entrance and the glass wall of the stairwell above it. The high flagpole on the roof of the building and its distinctive curved base structure emphasise the importance of the sanatorium. The connection between the glass corner and the rest of the facade makes it possible to find links with the work of architect Walter Gropius in Germany. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

Veel: 1930s, architect: August Volberg

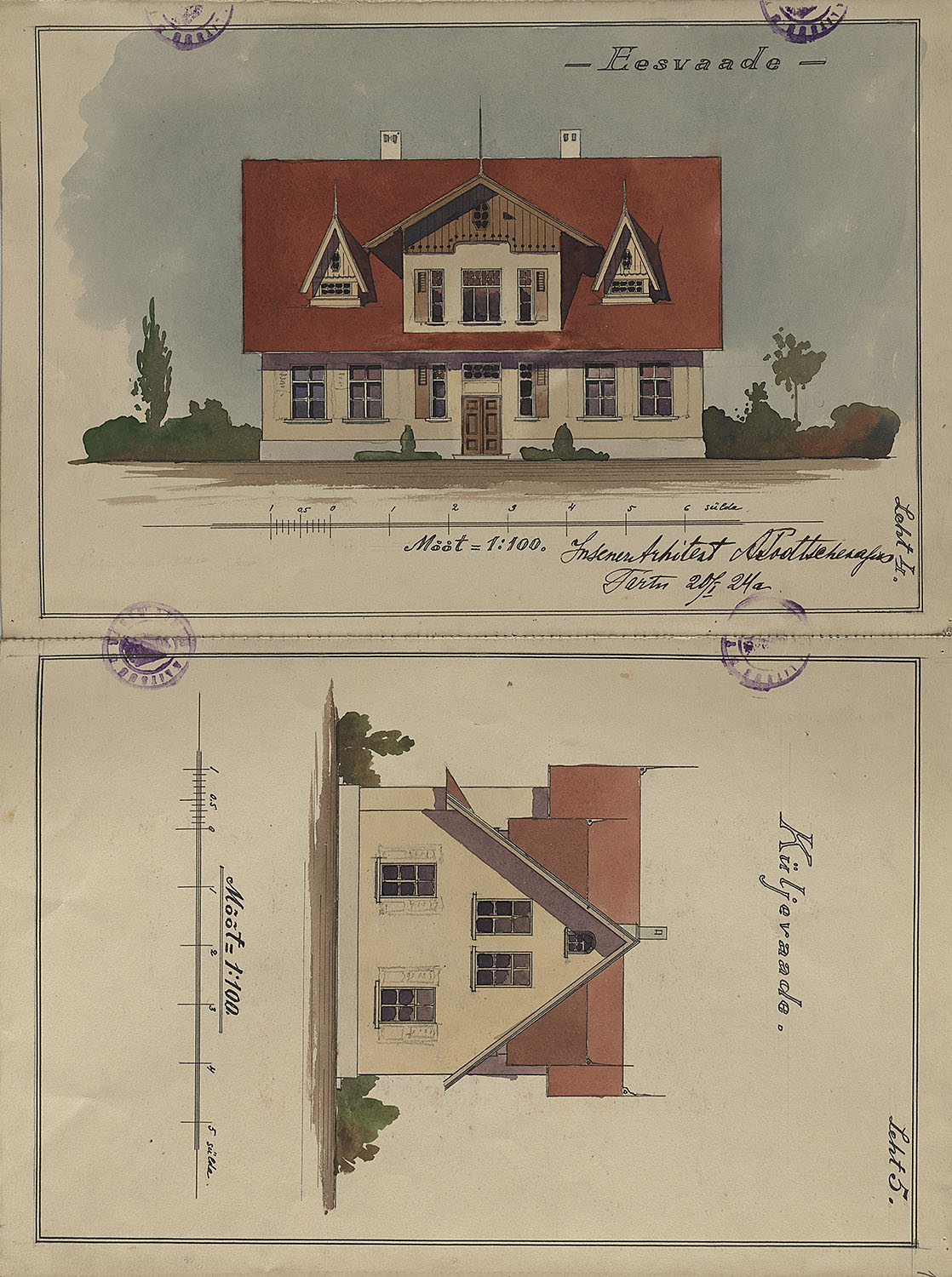

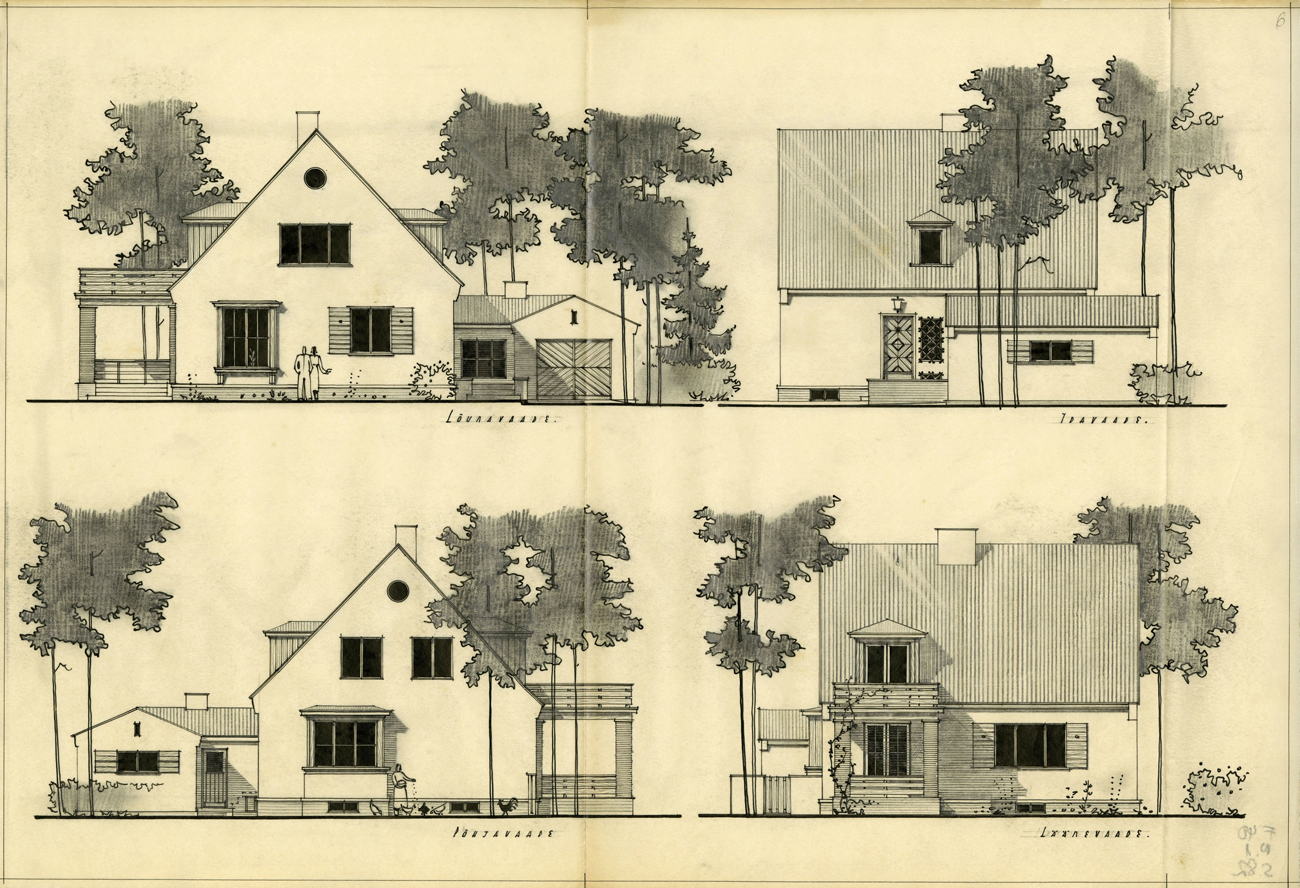

Residential building in Tartu Tamme district

Anatoli Podtšekajev, 1924. EAM 2.2.249

The architect Anatoli Podtšekajev, born in 1879 in the town of Opochka in the Pskov region, has left a unique mark on Tartu’s architectural history. Podtšekajev began his architectural studies at the Warsaw Polytechnic Institute. After the closure of the institute in 1905 and a subsequent break of a few years, Podtšekajev continued his studies at the Riga Polytechnic Institute, from which he graduated in 1910. Studying in two different schools and two different cities is probably the reason for the architect’s somewhat searching style, which seemed old-fashioned at the time. The architect moved to Tartu in the early 1920s, where he soon took up the post of city architect. Podtšekajev designed a number of residential buildings in the Tamme district, but buildings designed with his participation can also be found in other areas of Tartu. The four-apartment house in Tammelinn, which belonged to Mihkel Puusepp, is a building with a peculiar layout. On the ground floor, there are two two-room apartments with separate kitchens, a storage room and a hallway. On the upper floor, there are two one-bedroom apartments. Each apartment has a toilet. An interesting feature of the project is the two adjacent staircases in the middle of the building, one accessible from the street and the other from the courtyard. Consequently, there are two separate entrances to each apartment, one leading to the entrance hall and the other to the kitchen. Architectural historian Robert Treufeldt has thoroughly researched the life and work of architect Anatoli Podtšekajev.

(klick on the picture to see more)

Veel: 1920s, architect: Anatoli Podtšekajev

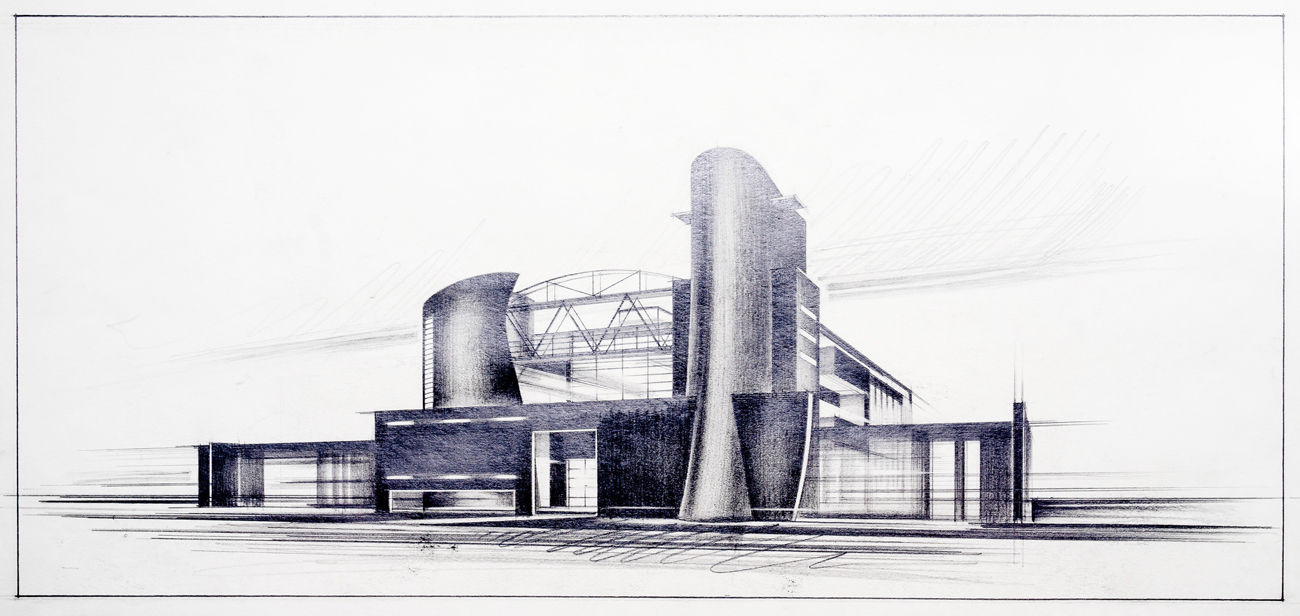

Leverex business centre

Andres Alver, Tiit Trummal, 1991. MK 223

In 1991, architects Andres Alver and Tiit Trummal designed a business centre on the territory of the former Kalev company on Pärnu road. The office building project, designed for Leverex, is characterised by a clear geometry of form, an articulated facade and a large glass wall surface on one side of the building. The 12-storey building was to include office space, a conference centre, restaurants, cafes, bars and saunas. A helipad was designed on the roof. A shopping centre with a showroom was planned next to the main building. The Leverex business centre is a timeless example of a project designed in the first half of the 1990s but never built. Architect Andres Alver donated the model to the museum in 2016. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(klick on the picture to see more)

Veel: 1990s, architect: Andres Alver, architect: Tiit Trummal

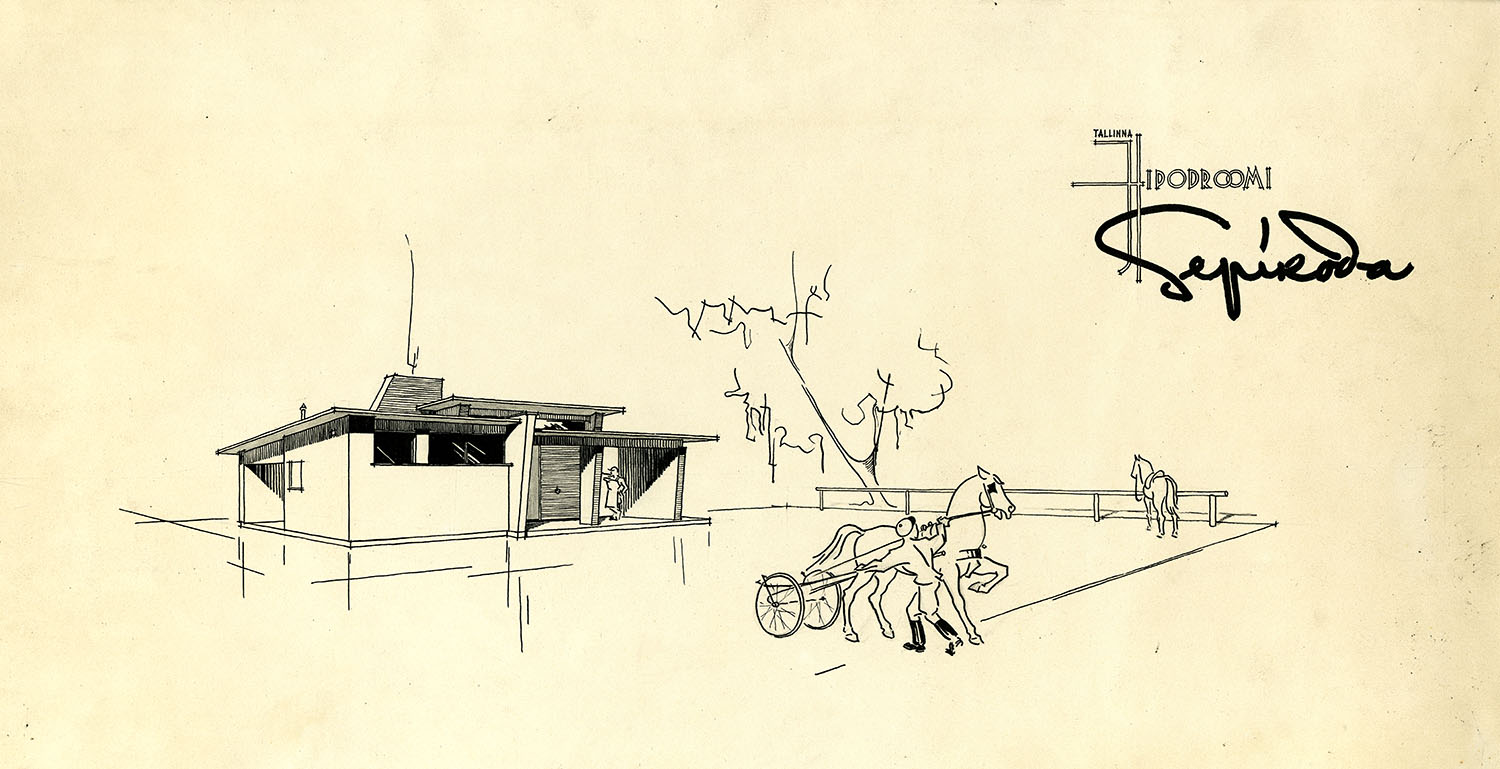

Smithy of the Tallinn hippodrome

Olev Randur. EAM 53.1.9

The grand opening of the Tallinn hippodrome took place on November 25, 1923. A suitable location for horse racing was found in a raw land between Paldiski road and Kopli Bay, neighbouring the Seewald hospital complex and the former Baltika brick factory. On the Paldiski road was a grand wooden gatehouse with ticket counters, designed by architect Karl Burman. The historicist wooden main building and grandstand were located next to the almost kilometre-long horse racing track. The limestone stable building, designed by architect Artur Perna, was completed in 1938 and is the only surviving building from the original hippodrome complex. During the Soviet period, the hippodrome was reconstructed, and new stables, a grandstand and a gate replaced buildings that had previously been destroyed and demolished. The design of the smithy by architect Olev Randur was probably completed in the second half of the 1960s, when he worked for SDI Eesti Maaehitusprojekt (state design institute of rural architecture) and a reconstruction plan for the hippodrome was drawn up. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

Veel: 1960s, architect: Olev Randur

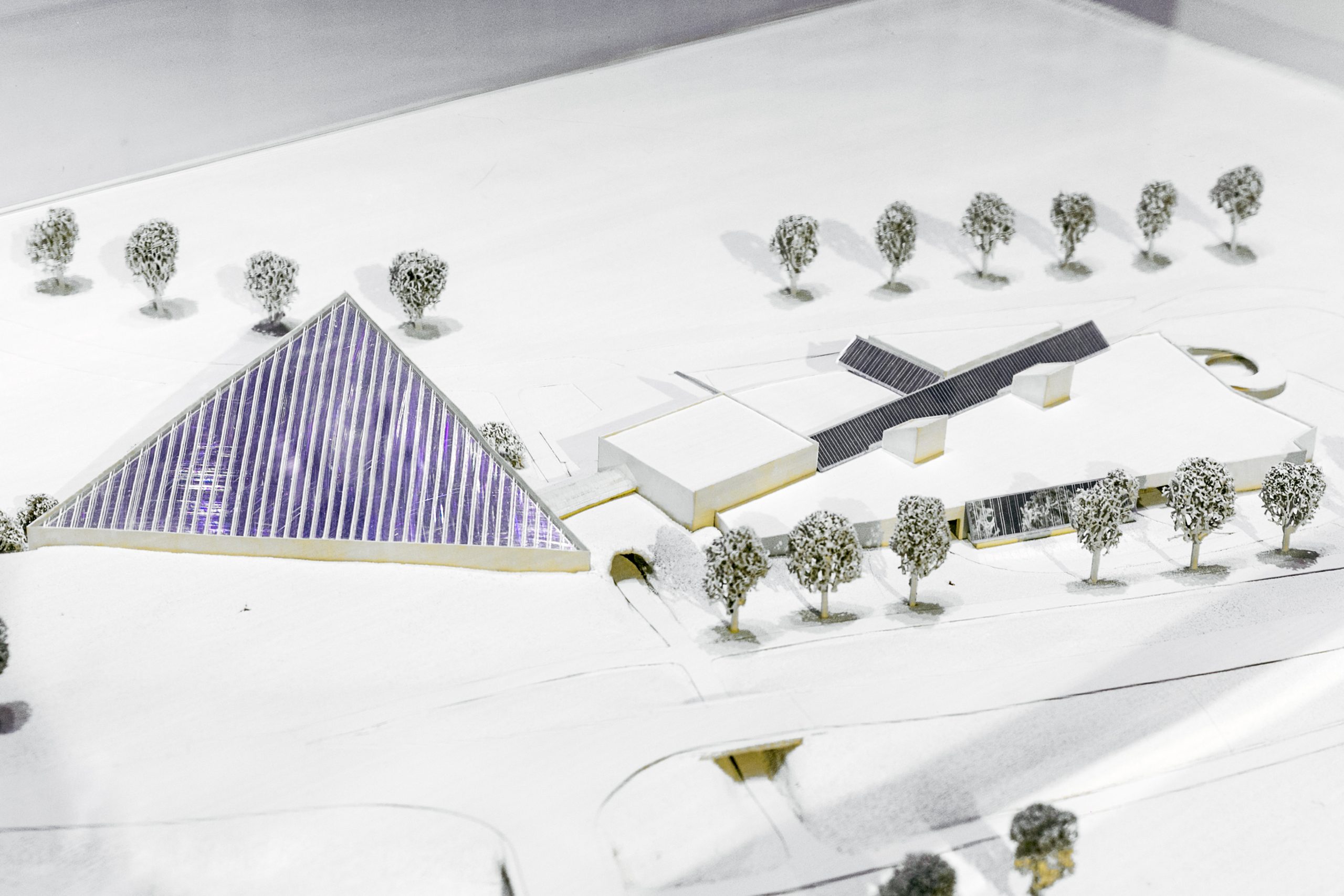

Botanic Garden administrative building

Ülevi Eljand, 1979. EAM MK 177

The establishment of the Botanic Garden on the land of President Konstantin Päts’ farm in Kloostrimetsa began in the late 1950s. Initially, staff offices and business premises were located in the former farm buildings. The new administrative building was designed by architect Ülevi Eljand in 1979, but the building itself was not finished until 1988. The small white asymmetrical building, located in a park meadow, is one of the few neo-functionalist buildings in Tallinn. The north part of the building has a conference hall on two floors, on the south side of the building is a connected conservatory with a swimming pool and fireplace. In contrast to the front facade, the garden side is articulated by a staircase descending from the second floor hall. The model of the building was donated to the museum by the Tallinn Botanic Garden in 2008. A year ago in November 2022, the model was exhibited at the Valga Museum as part of the jubilee exhibition of architect Ülevi Eljand (1947-2023). Text: Anne Lass

(klick on the picture to see more)

Veel: 1970s, architect: Ülevi Eljand

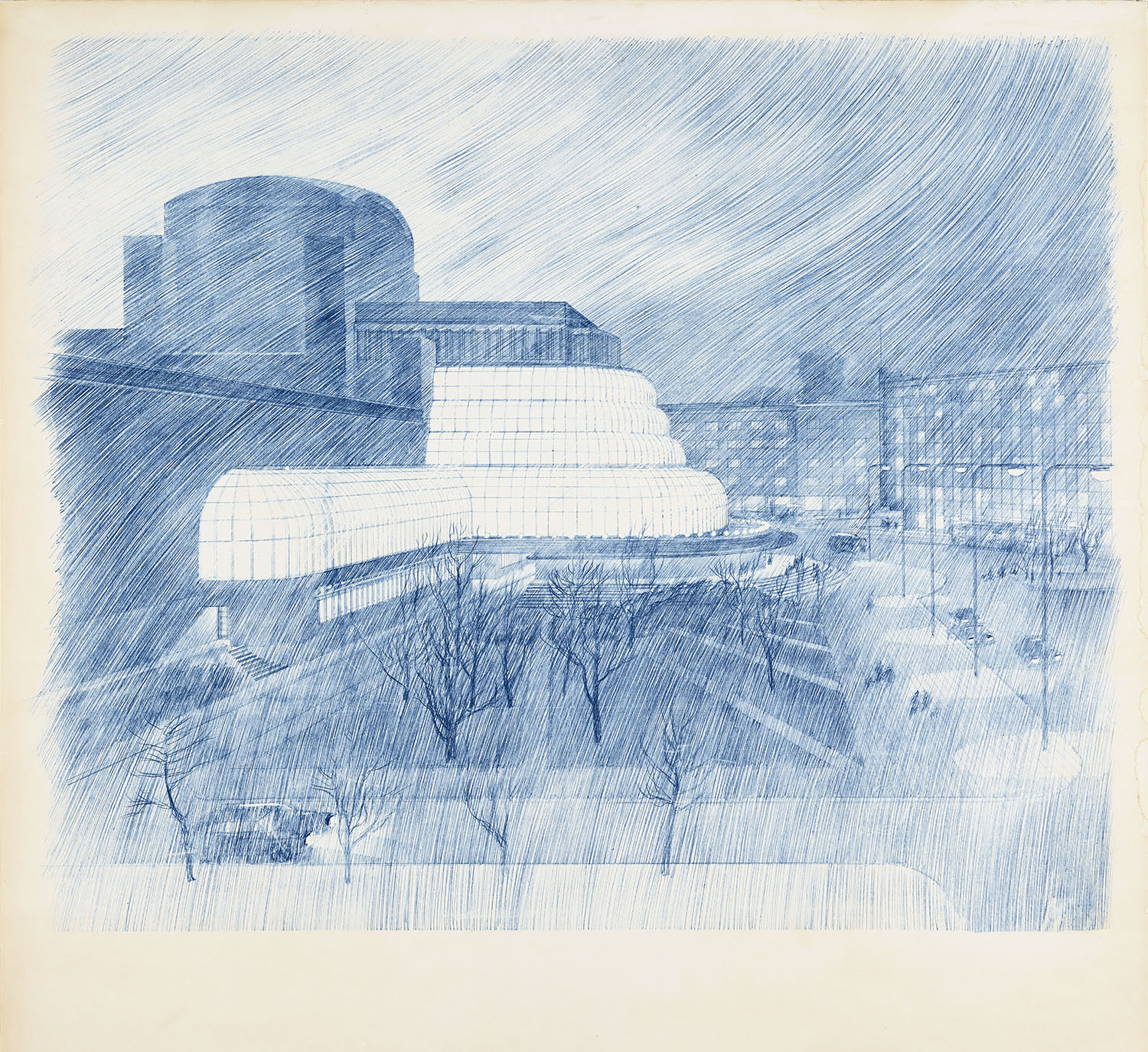

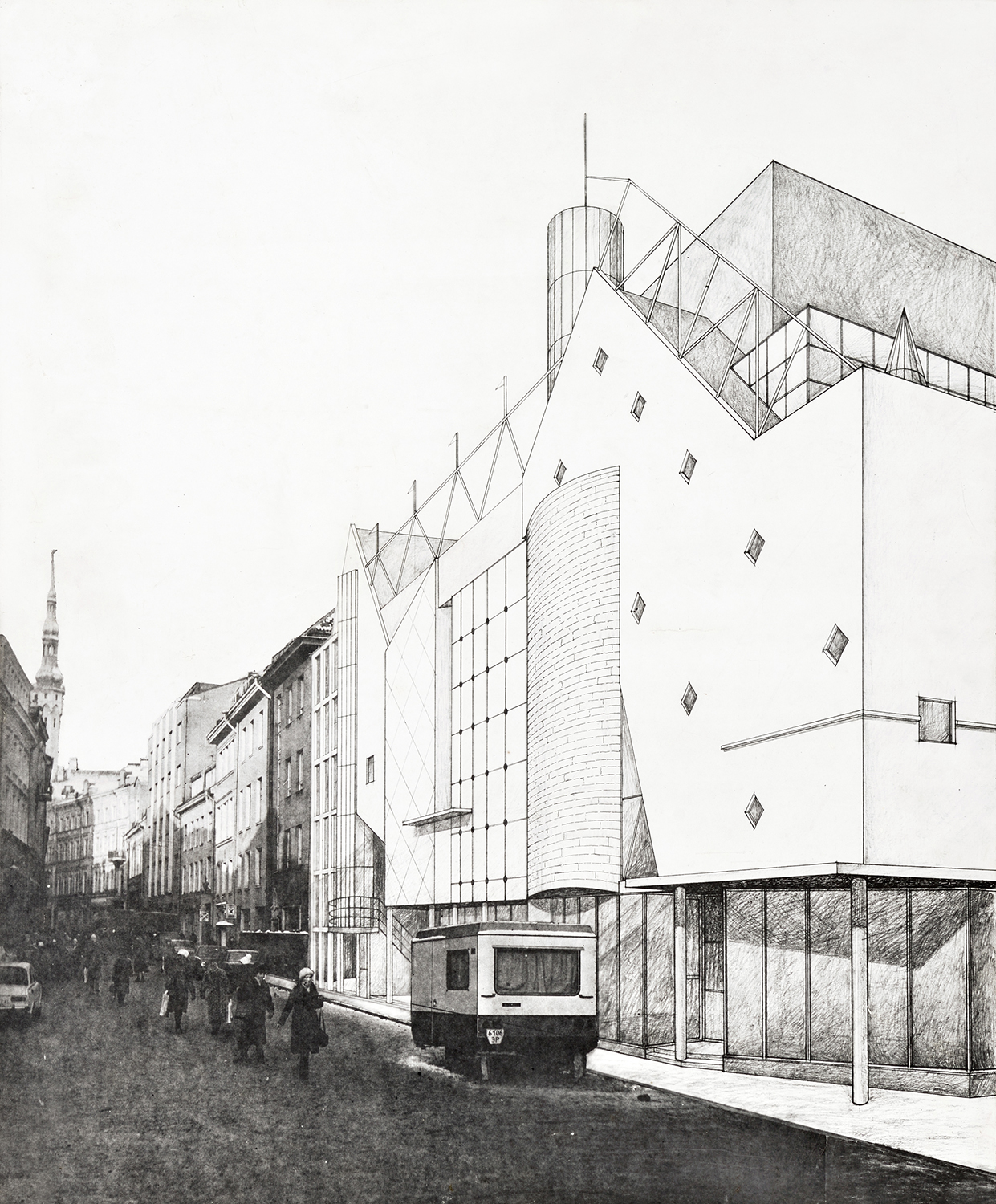

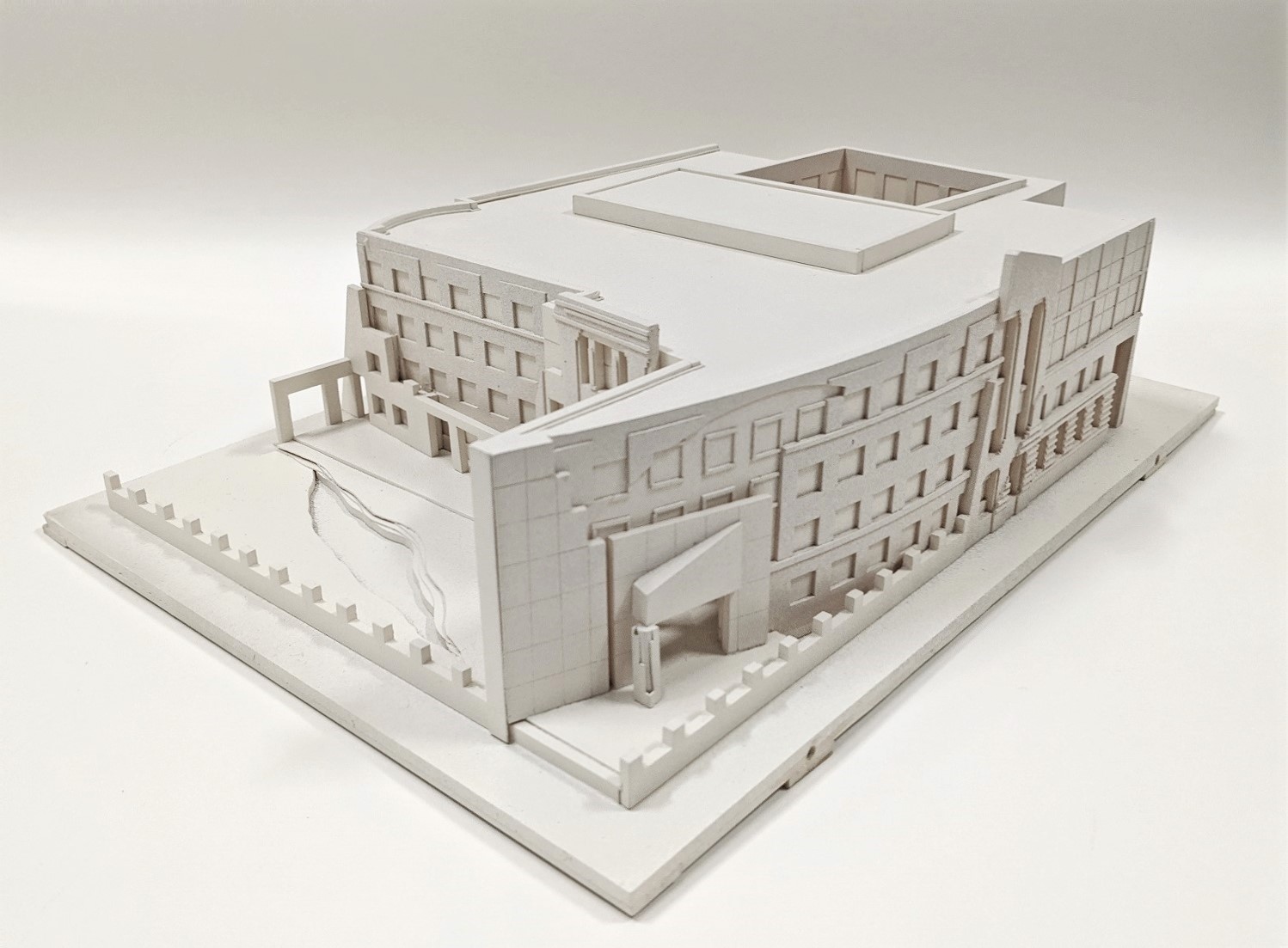

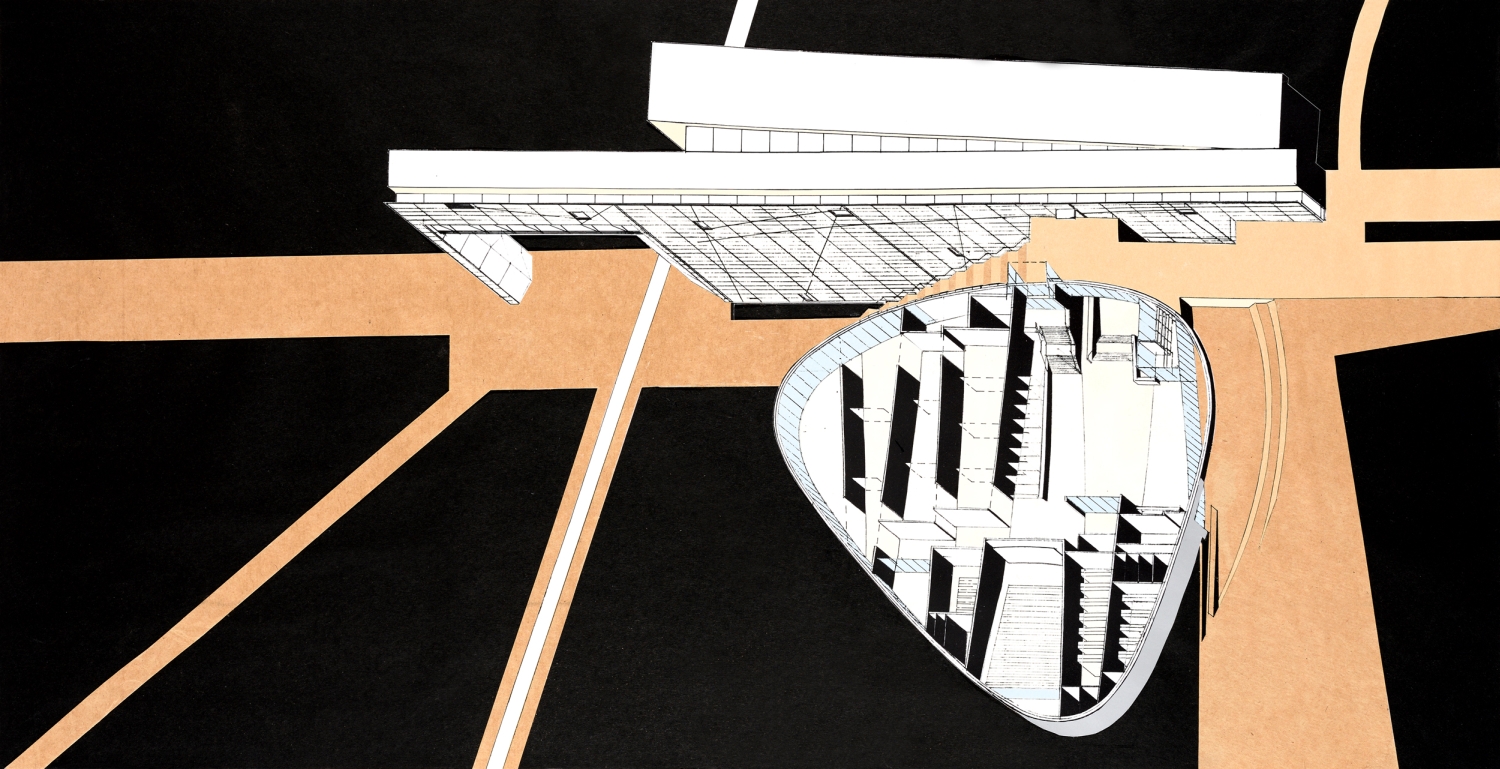

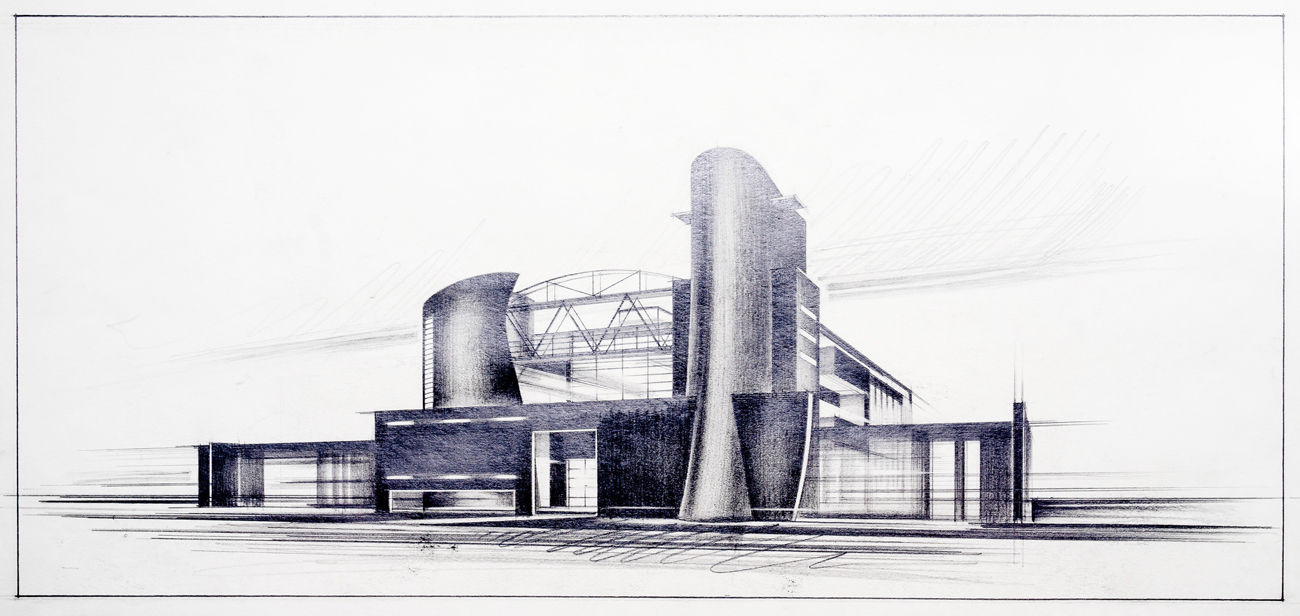

Opera and ballet theatre

Peep Jänes, Henno Sepmann, Rein Kersten, Loona Kikkas, 1986. EAM 5.4.35

Tallinn’s new opera and ballet theatre was planned to be built in the area of Süda Street, in the intersection of Pärnu Road, Süda Street and the planned extension of Rävala Boulevard. Architects Peep Jänes and Henno Sepmann won the invited architectural competition in 1984. A year later, together with architects Rein Kersten and Loona Kikkas, they began designing an opera theatre that meets modern requirements. The project of the new opera house was grandiose. The most spectacular part of the building, the brightest in the evening, was to be the curved glass facade. A powerfully shaped stage tower was to crown the central part of the building To balance the scale of the building, the choice of materials and colours was modest: grey reflective glass, silver grey glazed brick and dolomite, to make the building look harmonious with the historical buildings and Tallinn Town Wall. The theatre building’s large hall with four balconies had to accommodate 1,100 spectators. The choice of the location of the monumental building caused an active discussion in the society; there were both passionate supporters and ardent opponents. The new opera and ballet theatre would have significantly changed the milieu of the Süda Street area, the existing buildings would have been demolished and a number of trees, including the protected ginkgo tree, would have been cut down. To preserve the ginkgo, a square was planned in front of the opera house. The design process for the new opera house, which lasted several years, ended in November 1988 and the building was never constructed. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

Veel: 1980ndad, 1980s, architect: Henno Sepmann, architect: Loona Kikkas, architect: Peep Jänes, architect: Rein Kersten

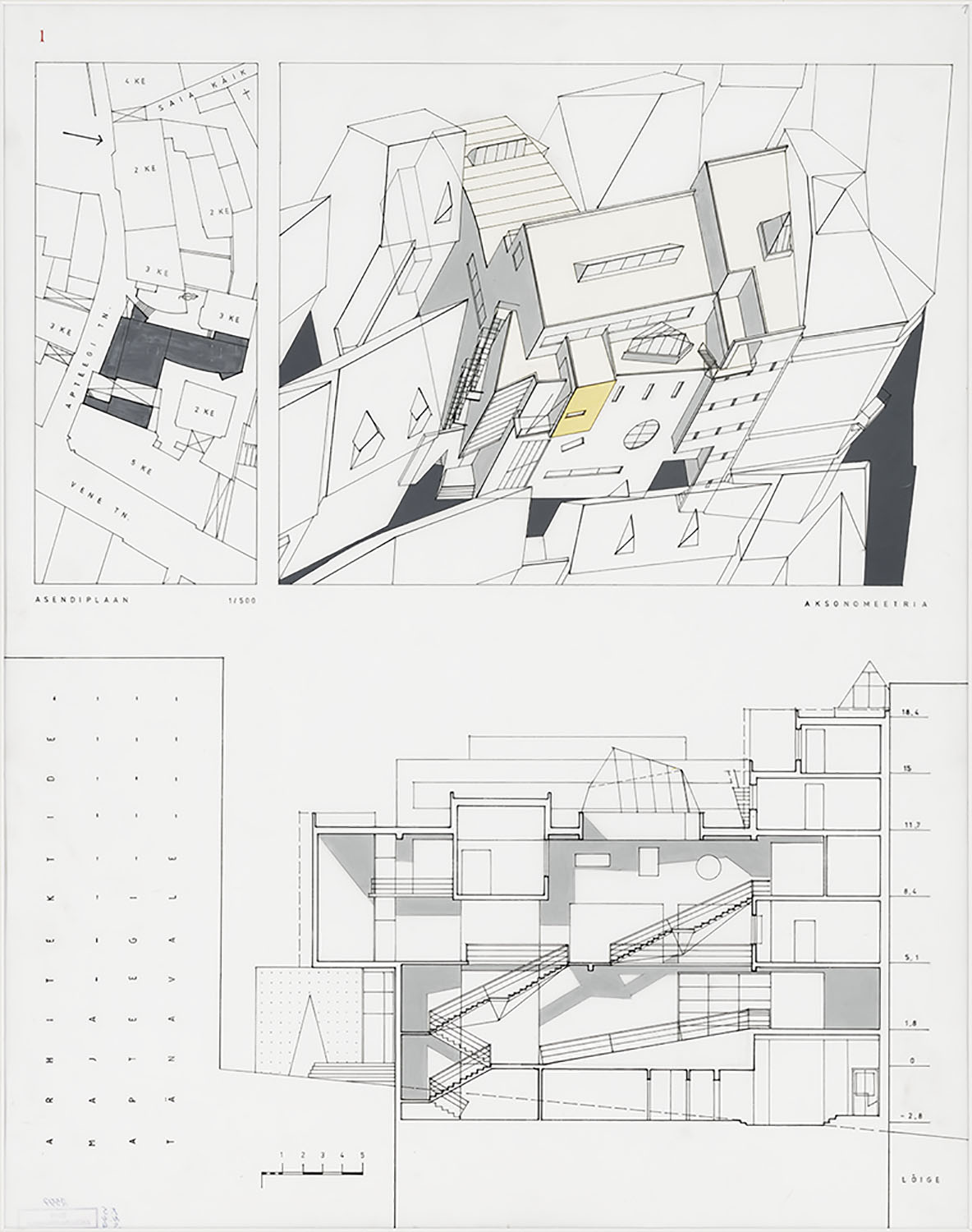

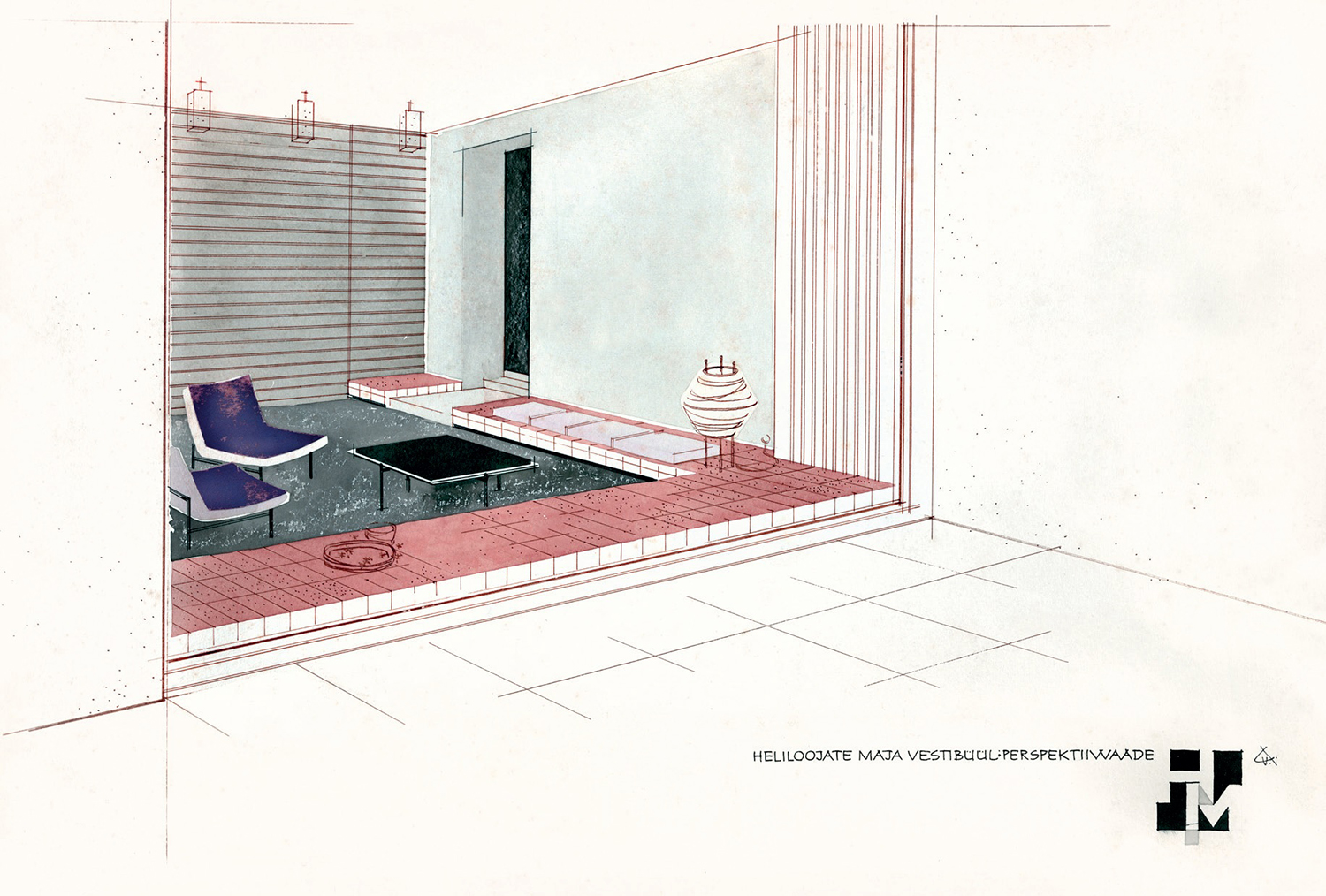

The Architects’ House

Andres Siim, 1989. EAM 5.4.9

The Architects’ House was to become the centre of Estonian architectural life, replacing the buildings destroyed during the war on the Apteegi Street in Tallinn’s old town. Among the 11 entries in the architectural competition, which ended in the spring of 1989, the design “Eclipse” by architect Andres Siim stood out. His work corresponded to the vision of the architects’ house and was awarded the first prize in the competition. The building had to be based on the structure of historically developed properties in the old town; the new building had to represent contemporary architecture in a dignified manner, while the volume of the building, the articulation of the facade and the roofscape had to match the milieu of the old town. The jury highlighted the conformity of the external and internal spatial solution, the multi-layered and interesting floorplan of the Architects’ House designed by Andres Siim. The narrow plots, characteristic of the old town, were clearly reflected in the facade design of the building, the special-shaped windows and the yellow section of the building added character. In addition to work and meeting rooms, a hall and library, cinema projection, archive and exhibition rooms and a cafe-club room were planned for the Architects’ House. Although the design of the building received positive feedback, the future progress of the project was difficult. The dream of an architects’ own house faded behind the bureaucracy of the authorities, construction and financial issues. A noteworthy project was not built. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(klick on the picture to see more illustrations)

Veel: 1980ndad, 1980s, architect: Andres Siim

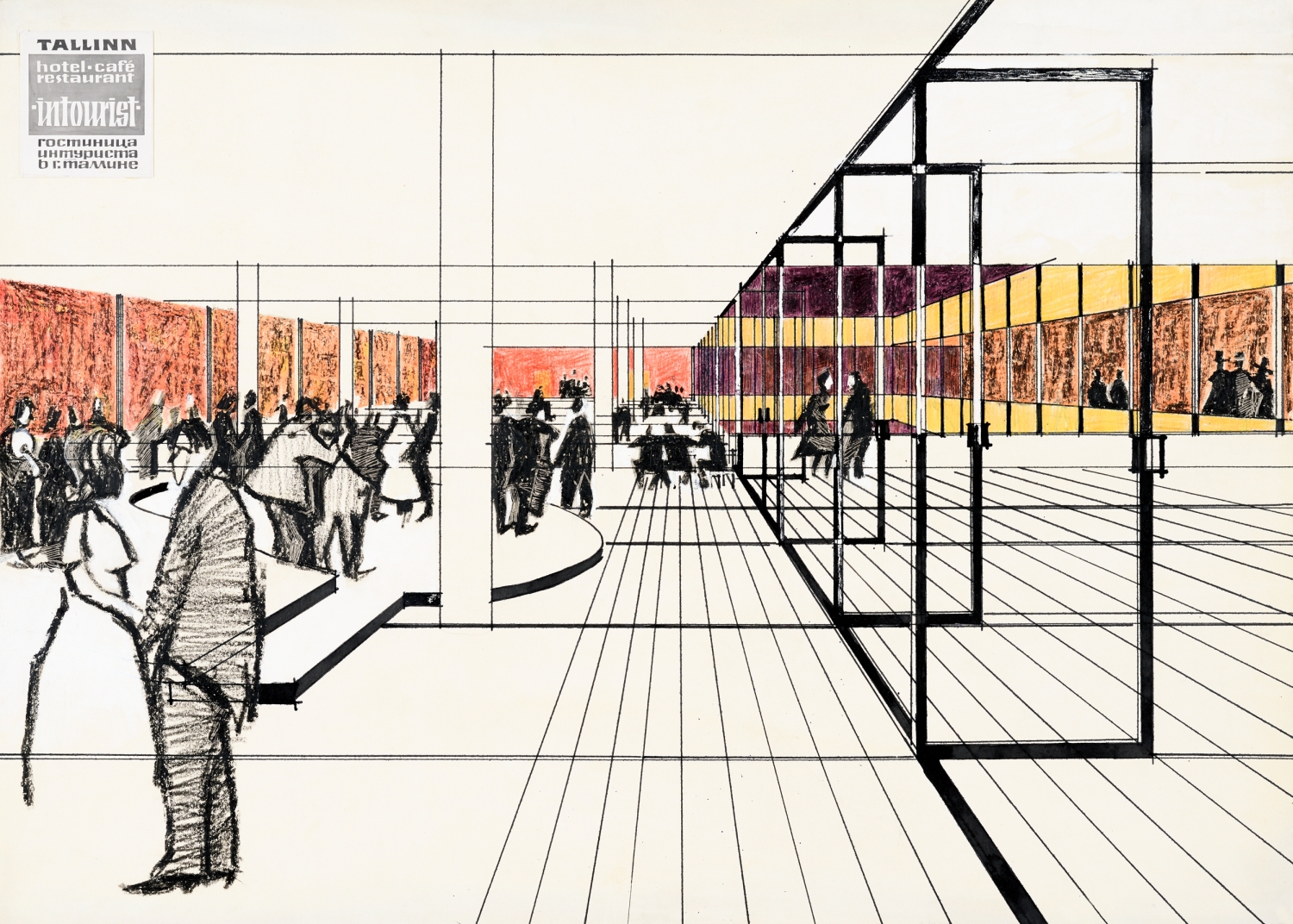

The passenger pavilion of the Port of Tallinn

Voldemar Herkel, Mai Roosna, 1965. EAM MK 174

The passenger pavilion in the Port of Tallinn was opened on July 7, 1965, when the travel connection between Tallinn and Helsinki, interrupted during the war, was restored. The pavilion, designed by architects Voldemar Herkel and Mai Roosna, reflected contemporary Finnish-influenced architecture. The walls of the pavilion were formed by shields with a load-bearing steel frame, which were filled with glass or partly with wood. The floor-to-ceiling glass walls of the building opened the view to the sea; wooden shields were used on walls where, based on the function of the rooms, more privacy was needed. In contrast to the wide white cornice of the horizontal roof, the building’s clapboards were covered with dark pine tar. Building ventilation and air heating pipes were placed inside the eaves, rainwater was drained from the corners of the roof. The unity of the interior and exterior of the pavilion was also important in the design. The suspended ceiling with strip lights used in the interior moved smoothly with the same rhythm over the ceiling of the canopy, the terraces of the building and the floors of the common rooms were covered with the same dolomite tiles. The partially landscaped courtyard in the middle of the building made the interior of the pavilion more spacious and added a little greenery to the harbour environment.There was a waiting room for international travelers in the seaside part of the pavilion, and a cafe-bar operated in the back of the room. A smaller waiting room in another side of the building was intended for passengers of local ship lines. In addition, there were offices, a currency exchange point and the foreign tourism office Inturist in the pavilion. The passenger pavilion was demolished a few decades after its completion. The model of the building was made by Peet Veimer in 2008 for the exhibition “Architect and his time. Voldemar Herkel” curated by Karin Hallas-Murula. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

Veel: 1960s, architect: Mai Roosna, architect: Voldemar Herkel

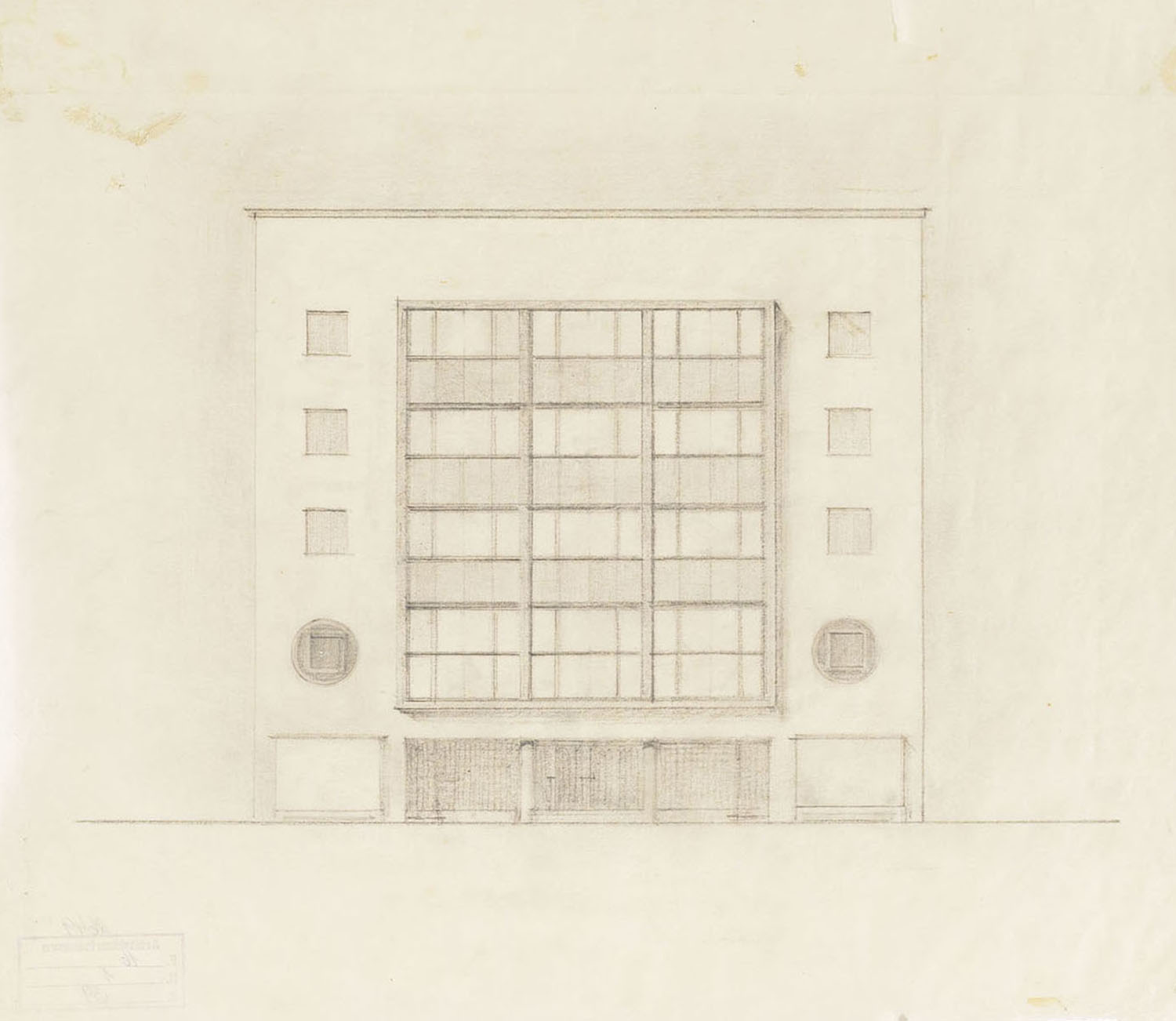

Sketches of the facade of the Tallinn Art Hall

Anton Soans, Edgar Johan Kuusik, 1932-1933. EAM 16.1.39

Designed by architects Anton Soans and Edgar Johan Kuusik, the Tallinn Art Hall is one of the most outstanding examples of functionalism in Estonia. In order to find the most suitable facade design, the architects sketched different solutions – the drawings show different designs for the entrance to the building, the arrangement of windows and the details on the facade. The facade solution of the building also changed slightly during the construction works, when the initially planned round windows were replaced with vertical niches. The cornerstone of the Tallinn Art Hall was laid on August 29, 1933, and it was officially opened with an art exhibition on September 15, 1934. The modernity of the originally five-storey building with a T-shaped ground plan is emphasized by the main entrance of the building that is stepping back from the street line and the central part of the front facade that is resting on two pillars, as well as the flat roof of the building. The glass screen located in the middle of the facade, as if placed inside a frame, connects the artists’ studios, office spaces and exhibition hall located on different floors on the facade into one. In 1937, the bronze figures “Work” and “Beauty” designed by the sculptor Juhan Raudsepp were placed in the niches of the facade. According to the project of Edgar Johan Kuusik, the last floor of the Art Building was rebuilt in 1962, as a result of which the building became as high as the adjacent Art Foundation building (architect Alar Kotli). In 1993, Ado Soans, son of Anton Soans, donated the facade drawings to the museum. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(klick on the picture to see more illustrations)

Veel: 1930s, architect: Anton Soans, architect: Edgar Johan Kuusik

Writers’ House

August Volberg, Heili Volberg, 1958. EAM 31.1.37

The Writers’ House in Tallinn old town was opened in the spring of 1963. The project of the four-storey building was designed by the architects August and Heili Volberg at the national design institute “Estonprojekt” in 1958. The seemingly laconic Writers’ House is characterized by the rationality typical of modernism. The regularly spaced windows indicate the different functions of the building – spaces for public use are located behind the large windows, private living spaces are hidden behind the smaller three-part windows. The building is connected to the historical architectural environment by a high pitched roof that fits the rooftop landscape of the old town. On the ground floor next to Harju Street, there was a book store called “Lugemisvara” with large display windows. On the corner of Harju and Vana-Posti streets, the cafe “Pegasus” with a modern interior design is located on three floors. A vestibule with a wardrobe and auxiliary rooms were originally planned in the first floor. On the next two floors are the halls of the cafe, the windows of which offer a view of St. Nicholas Church, the verdant green area and the Eduard Vilde monument. The floors of the cafe are connected by a spiral staircase. The premises of the Estonian Writers’ Union and a 150-seat meeting hall with an expressive black ceiling are located in the three-storey part of the building facing Kuninga Street. There was also space for the editors of the “Looming” magazine and the Literary Fund. In addition to the public function, two to five room apartments for writers and their families were planned in the building. In the larger apartments, one room was planned as a writer’s workspace. During the later reconstruction, the fifth floor of the house, under the roof, was built. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(klick on the picture to see more illustrations)

Veel: 1950s, architect: August Volberg, architect: Heili Volberg-Raig

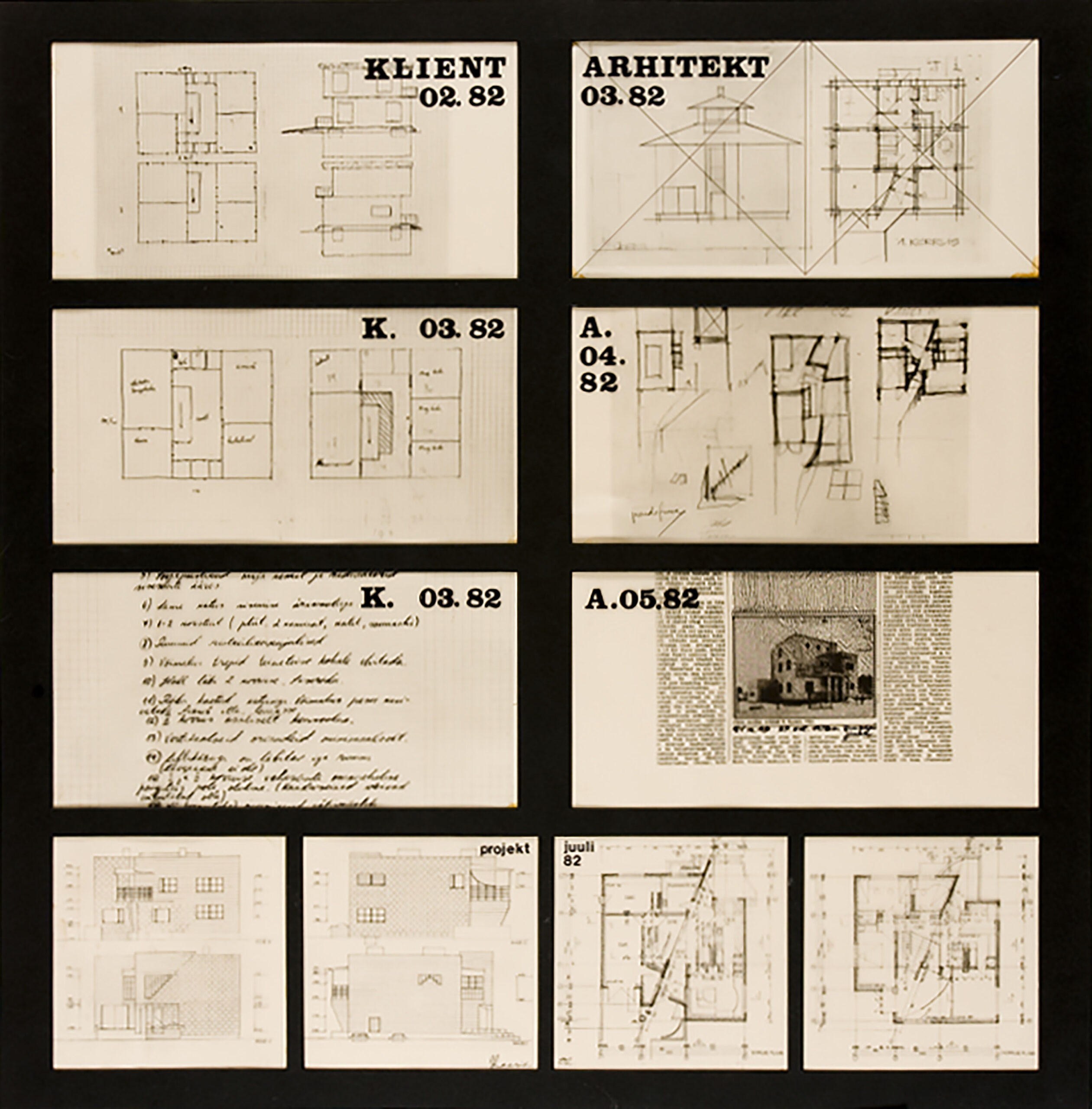

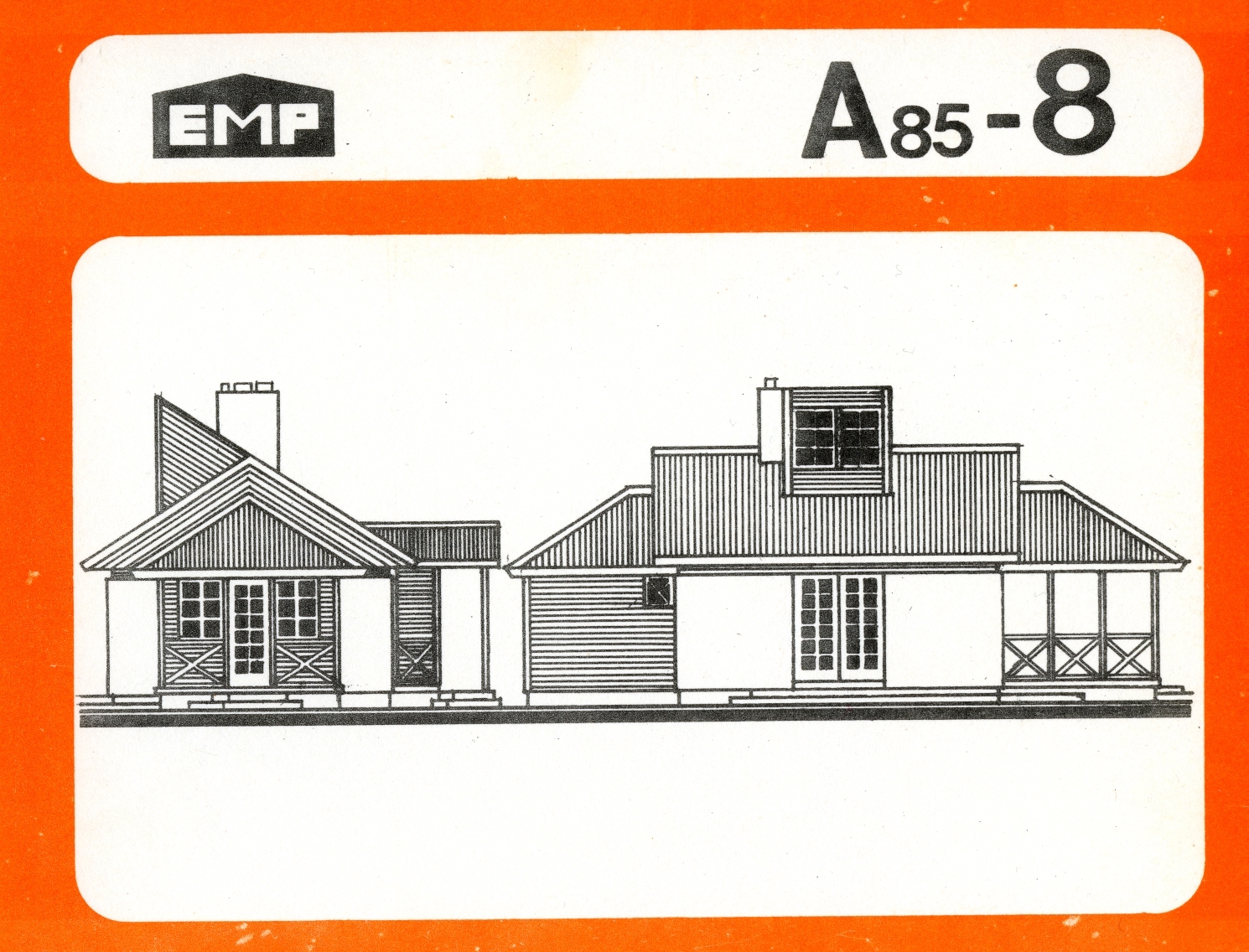

Dialogue “Client-architect”

Veljo Kaasik, 1982. EAM K 31

“Client-architect” by Veljo Kaasik is a visual dialogue between the architect and the client. The work depicting the design process of a private house located on Nisu Street in Tartu shows how the building is completed in cooperation between an ambitious architect and a demanding client. Both parties are connected to each other from the planning of the building until its completion. The architect’s imaginative ideas are often influenced by the different sense of aesthetic and disagreements of the parties involved. Mostly, compromises are made. The final result is more or less different than originally planned. Veljo Kaasik’s work was on display at the exhibition of ten architects in the salon of the Tallinn Art Hall Gallery (exhibition 23.12.1982–9.01.1983). Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

Veel: 1980ndad, 1980s, architect: Veljo Kaasik

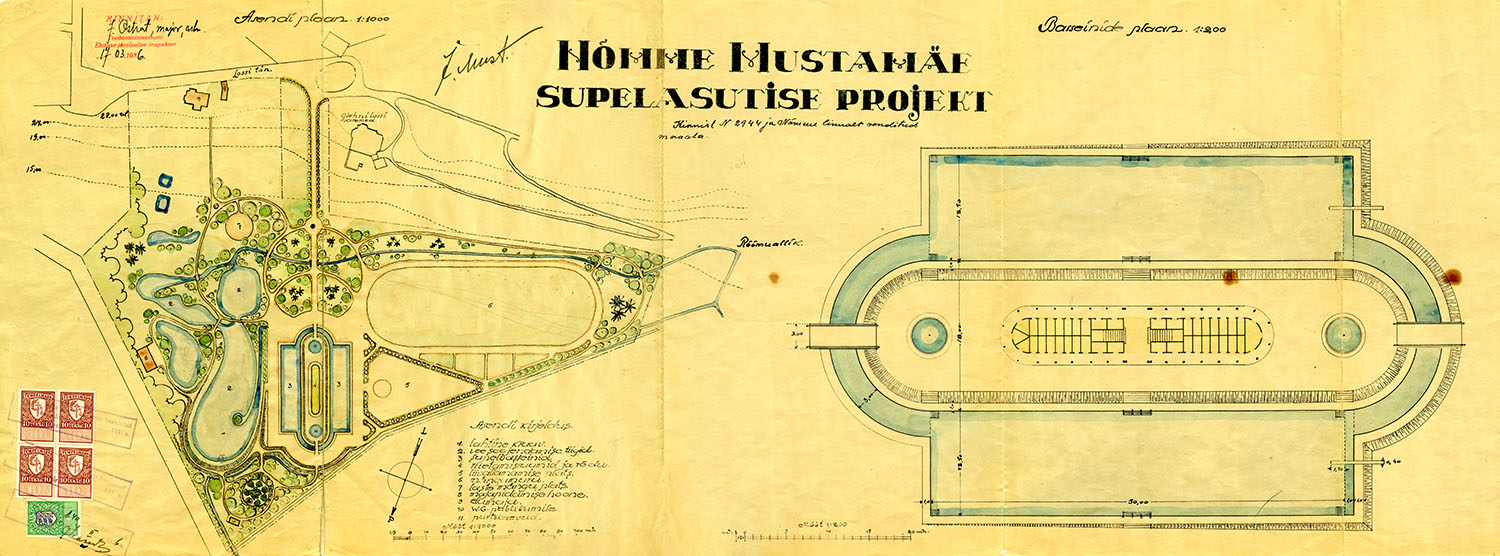

Mustamäe bathing facility

Tõnis Mihkelson, 1936. EAM 2.6.53

Under the lead of entrepreneur Johan Must, a bathing facility was built in Nõmme under the slope of Mustamäe. The town of Nõmme granted a construction permit for the facility in 1927, but the construction work was delayed due to land ownership disputes. In 1934, Johan Must acquired the necessary land. He received a loan from the Ministry of Economy to build a bathing facility, construction work began in the fall of 1935. Mustamäe bathing facility was designed by architect Tõnis Mihkelson. In 1936, a cafe building and a 50-meter swimming pool were completed. A year later, changing rooms, another slightly deeper pool, a water jumping tower and a swan pond were opened. In order to obtain a water temperature suitable for swimming, cold spring water was directed through four pre-heating pools, and artificial waterfalls were built to ensure water quality. A functionalist wooden cafe building was located between the two swimming pools. There were dressing rooms on the first floor, a balcony and a separate area for the orchestra on the second floor. In addition, a staircase was planned on the slope of Mustamäe, which led to Nõmme’s garden city. Domestic and international swimming competitions were held in the swimming pools, chess tournaments were regularly held in the cafe building. In winter, people could enjoy winter swimming and ice skating.The cafe building of the Mustamäe bathing facility was destroyed in 1974. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(klick on the picture to see more illustrations)

Veel: 1930s, architect: Tõnis Mihkelson

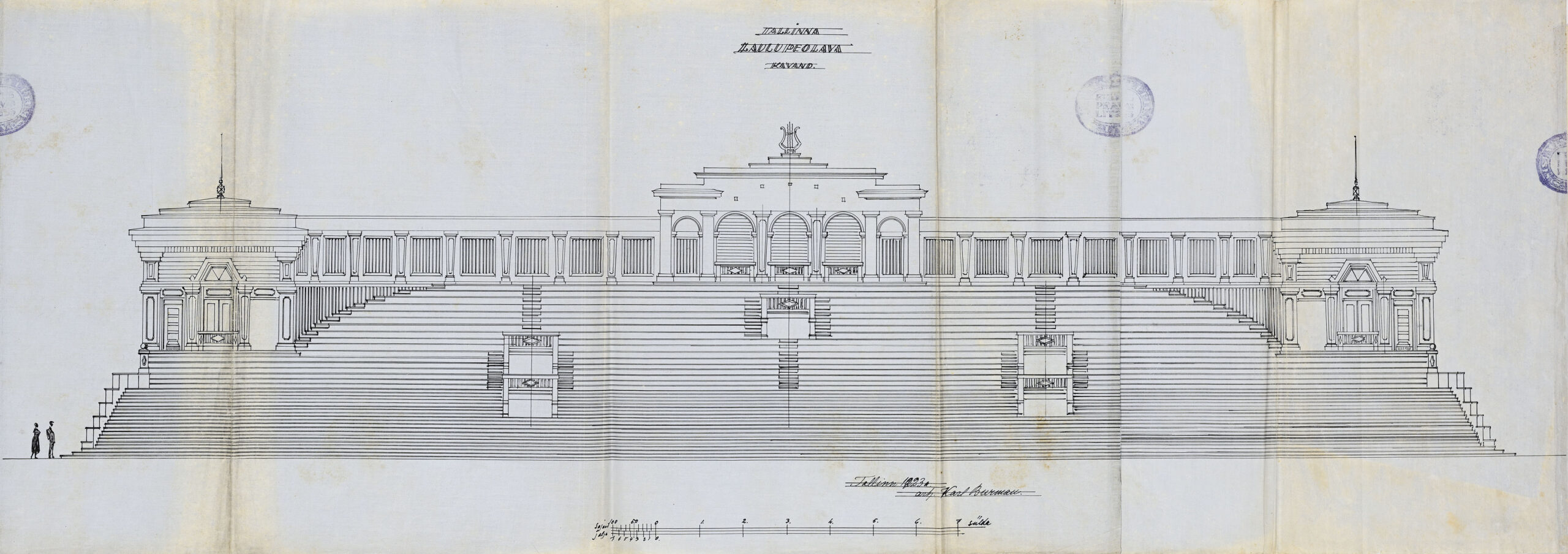

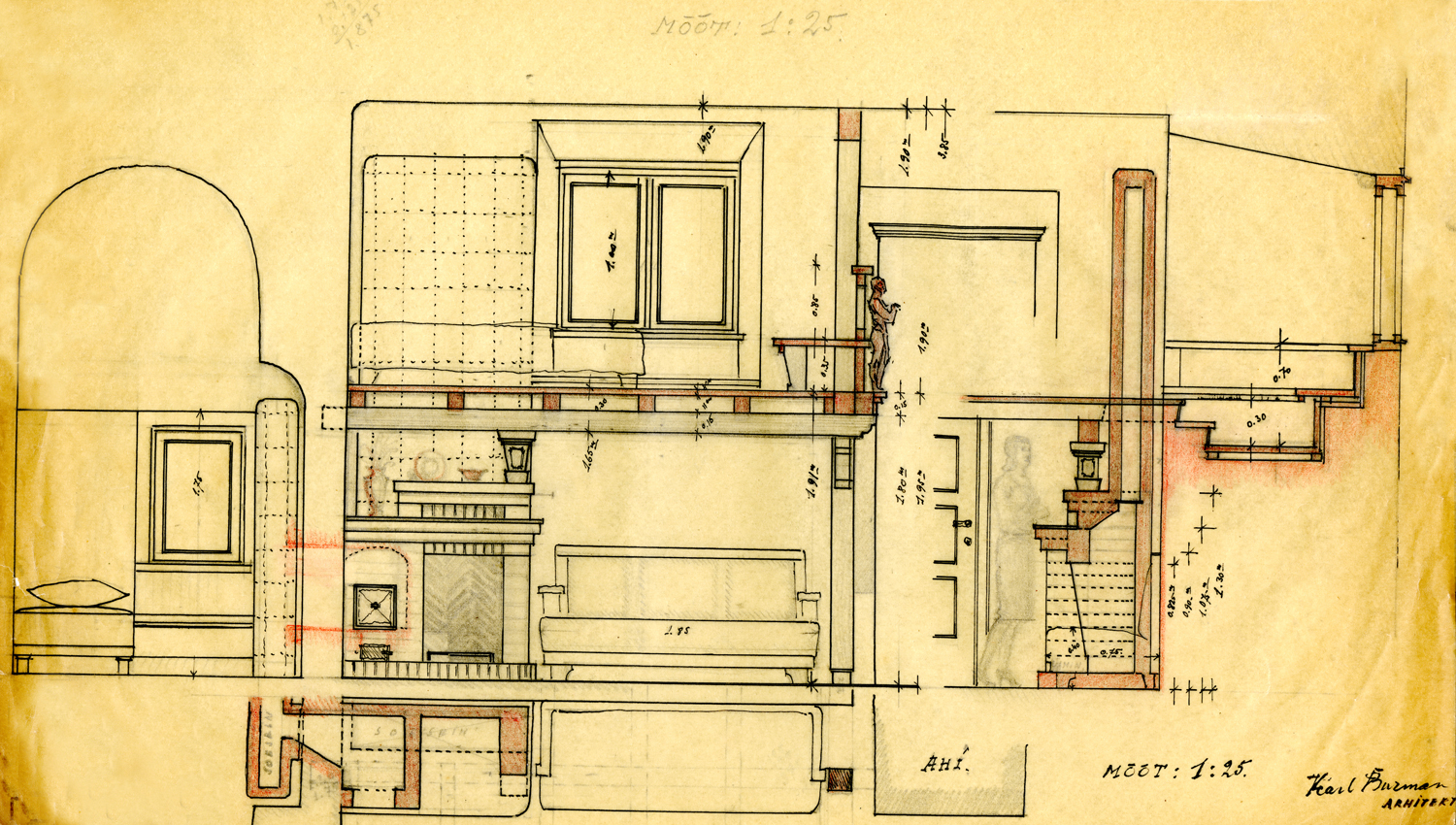

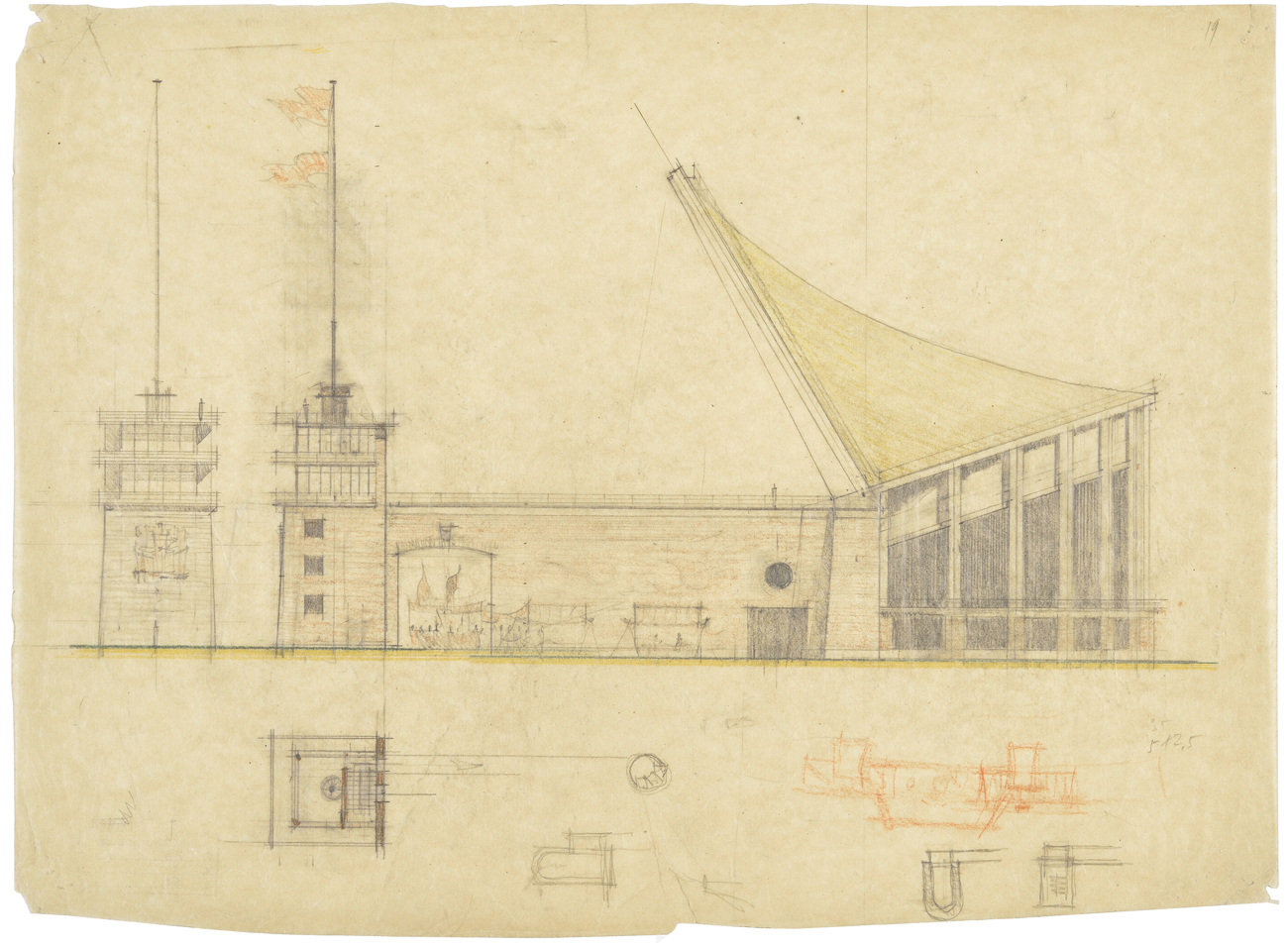

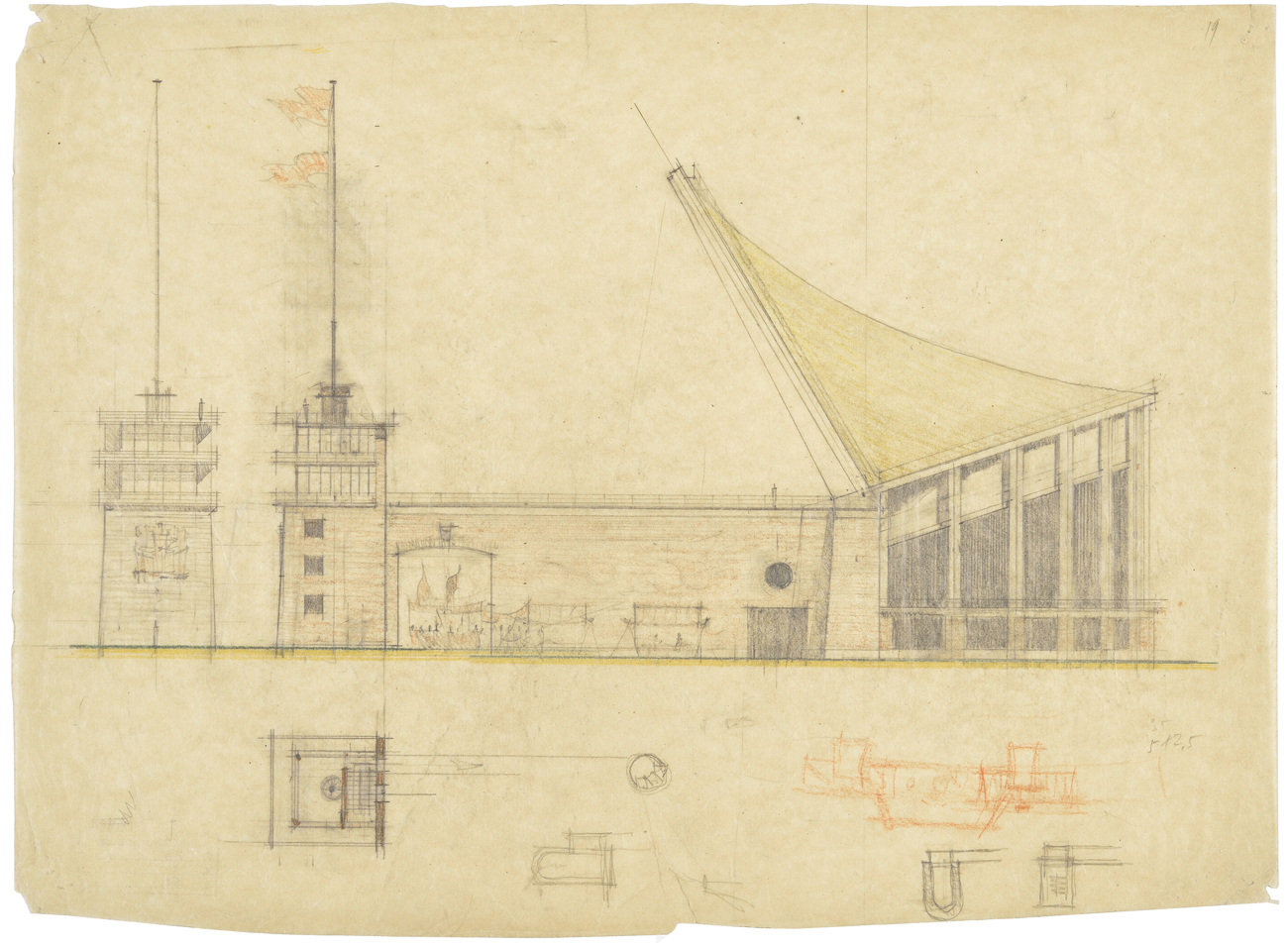

Tallinn Song Festival stage

Karl Burman, 1923. EAM 2.4.10

The VIII Estonian Song Festival was held in Tallinn in 1923. It was the first song festival of the independent Republic of Estonia. The festival site was located in Kadriorg (Roheline aas), where it was planned to build a stadium in the future. The song festival stage was designed by the architect Karl Burman. The project was approved in April 1923, and the stage was ready by the start of the festival on June 30. According to art historian Leo Gens, the imposing wooden building with a neoclassical look was one of the most outstanding works of the architect (see Leo Gens. Karl Burman. Monograafia. Tallinn, 1998). In 1926, the stadium was completed and the concert stage was adapted to the stadium grandstand. The building stood for the next 10 years, until a new reinforced concrete tribune designed by architect Elmar Lohk and engineer August Komendant (completed in 1938), one of the top buildings of Estonian modernist architecture and engineering, was built in its place (see Miracles in Concrete. Structural Engineer August Komendant. Compiled by Carl-Dag Lige. Tallinn, 2022). Tallinn Song Festival stage project was stored in the archive of the former National Construction Committee of the USSR, until it reached the collection of the newly created architecture museum in 1991. Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1920s, architect: Karl Burman

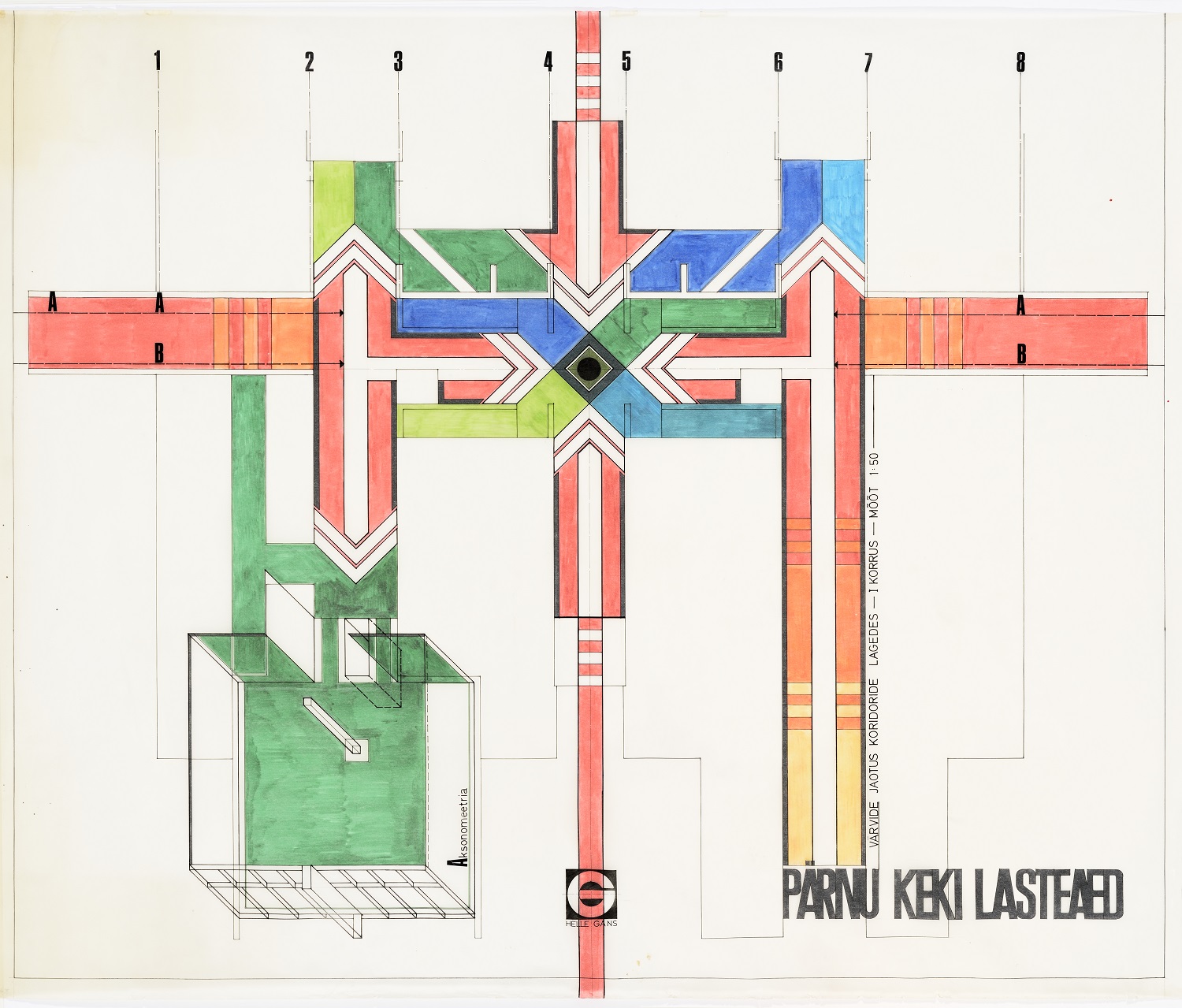

Pärnu Maritime School

Heili Volberg, 1970. EAM 51.1.4

In 1970, architect Heili Volberg designed an extension to the dormitory of the maritime school located by the moat in Pärnu. Spacious classrooms, an auditoorium and a sports hall, even a hairdresser’s office, was planned in the educational building. Pärnu Maritime School was closed and the project was not completed. The school dormitory was reconstructed and the Viiking health center was opened in the building at the beginning of August 1993. The boards of Pärnu Maritime School were designed by interior architect Aate-Heli Õun using the collage technique. The work was donated to the museum by architect Heili Volberg-Raig in 2013. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(klick on the picture to see more illustrations)

Veel: 1970s, architect: Heili Volberg-Raig

Children’s park in Sindi

Nora Tammoja, 1964. EAM 11.1.32

Landscape architect Nora Tammoja has created numerous projects for urban green areas, cemeteries and children’s playgrounds. The design of children’s park in Sindi (Sindi Lastepark) was completed in 1964, the co-author of the project was architect Kaarel Pedak. The playground included playhouses and shelters, a climbing and sledding hill with a tunnel inside, a swing area, a traffic lane, a sandbox and a Robinson square. Robinson square was a playground construction site where children could build various buildings according to their imagination. The materials needed for construction were collected from various construction sites and were placed in the material warehouse on the playground. Since construction was considered primarily a boy’s activity, a separate play area for girls was planned in the park. The girls’ playhouse consisted of several rooms, one of which had a toy stove, and there was also a shop-pharmacy. In the middle of the playground was a two-way traffic lane with crosswalks and traffic signs. In the centre of the track was a circular traffic island intended for the position of a traffic controller. Sindi Lastepark with various play elements was mainly intended for preschool children and students of younger grades. On the back side of the project photo (EAM 11.1.69), it is noted that the work was awarded a silver medal at the National Economic Achievements Exhibition in Moscow in 1964. Construction work on the children’s park began in 1965, but probably not everything planned was completed. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(klick on the picture to see more illustrations)

Veel: 1960s, landscape architect: Nora Tammoja

Ellamaa power plant annexe

Peeter Tarvas, 1943. EAM 40.1.1

The Ellamaa power plant was opened on May 9, 1923. The outstanding industrial building, designed by architect Aleksandr Wladovsky, consisted of a switch and transformer building, a machine building, a peat gas generator building and a tower with a water tank at the top. By the end of the decade, the rapid growth of electricity consumption made it necessary to add a few buildings to the complex. During the war in 1941, a part of the power plant exploded. The building was soon restored according to a slightly different project from the original one, an extension was planned to increase the production capacity. In 1943, architect Peeter Tarvas prepared project for the restoration and reconstruction of the power plant. The architect placed a water tower in the center of the drawing, in the foreground are new substations added to the existing building. The annexe designed by Peeter Tarvas was not implemented. The Ellamaa power plant was closed in 1966, when the power supply was taken over by the kerogenite power plants located in Ida-Virumaa. The boiler house, which was completed in 1929, continued to operate and supplied the Turba village with room heat for a few decades after the power plant closure. Since 2018, the Motorsports Museum MOMU has been operating in the Ellamaa power plant building. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

Veel: 1940s, architect: Peeter Tarvas

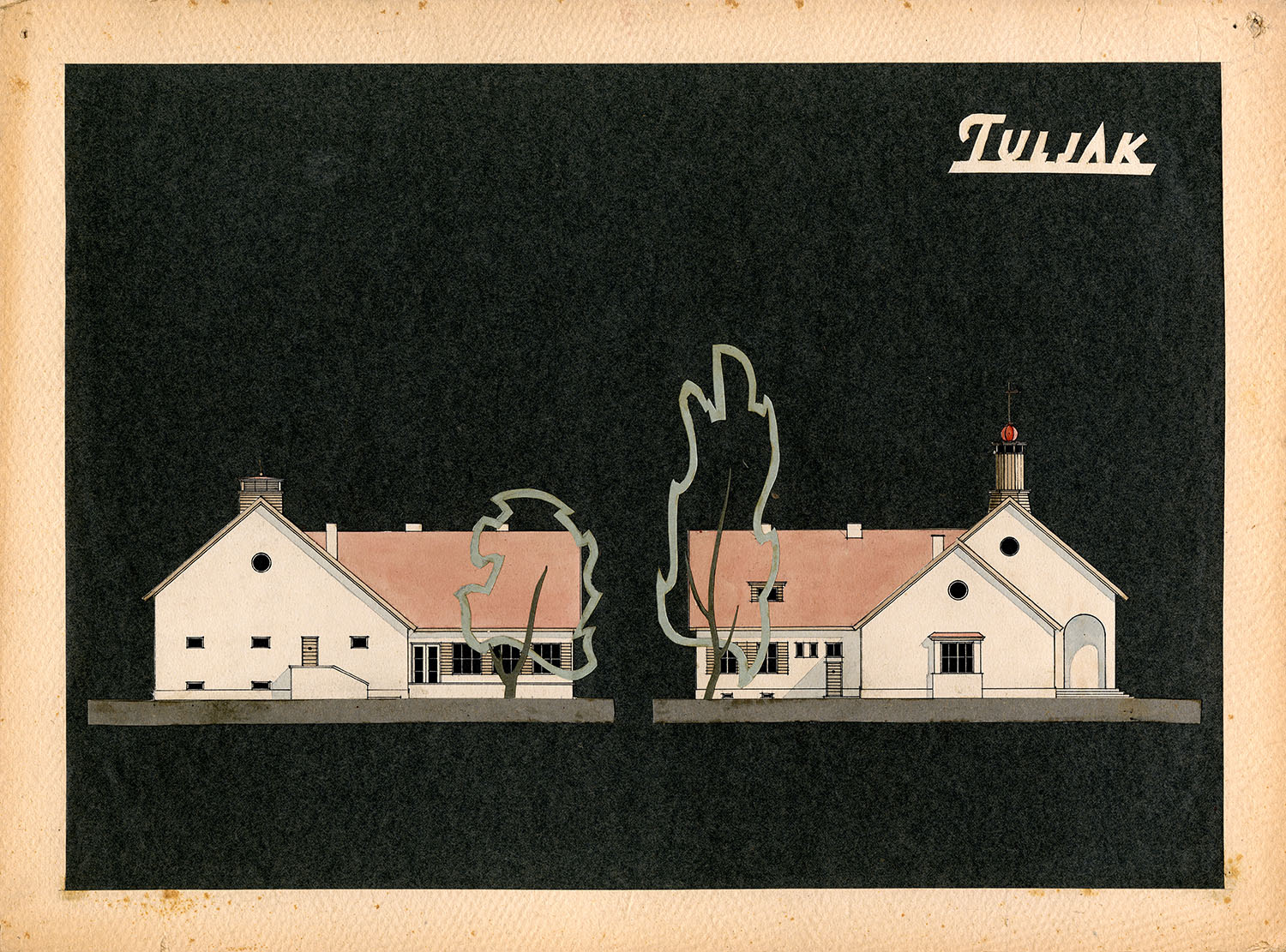

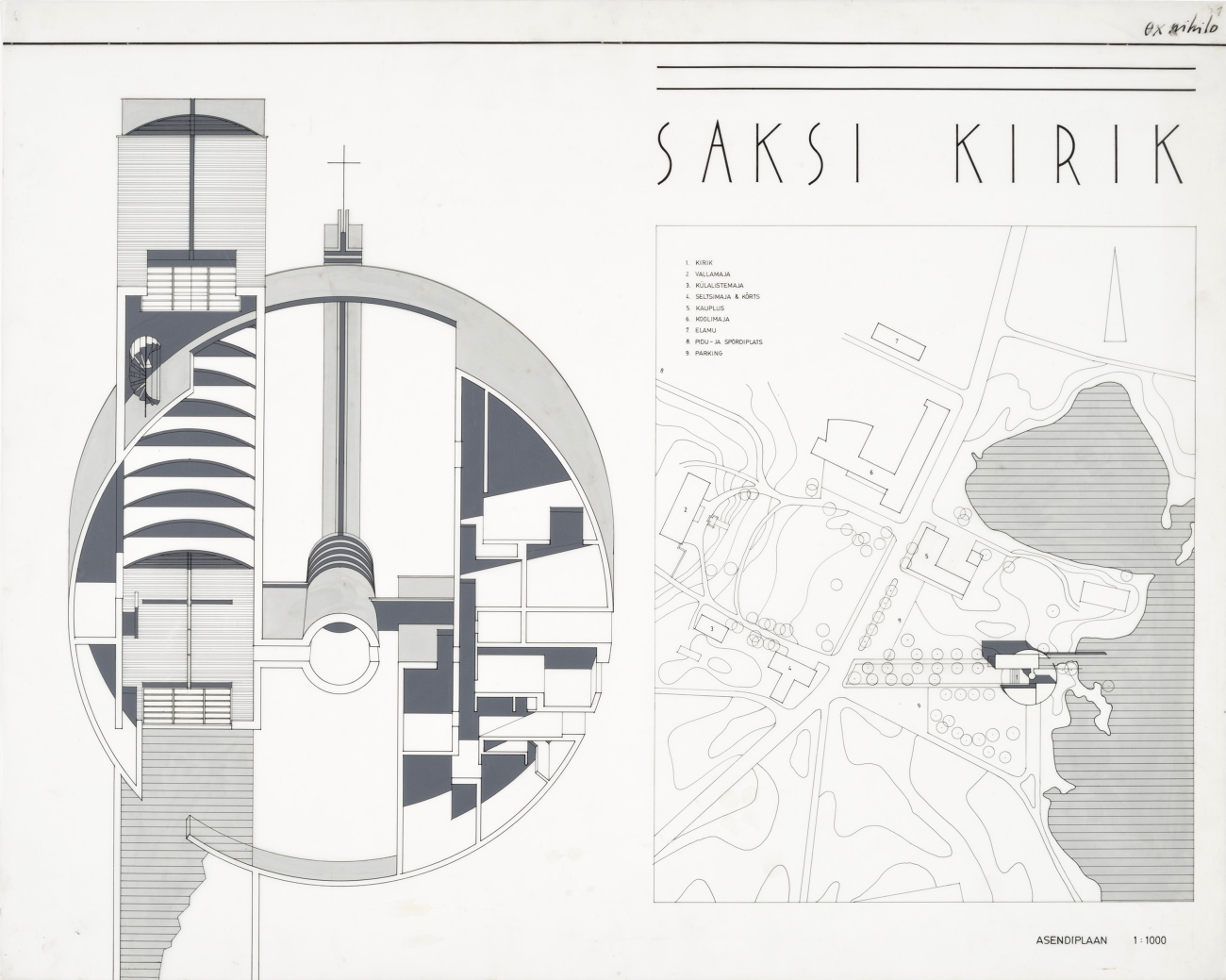

Competition works of rural cultural centre

EAM 3.4.9; EAM 3.4.12; EAM 3.4.14

At the end of 1947, an architectural competition was organized to find the best solution for the standard project of rural area cultural centres. 40 concept designs were submitted to the competition. Despite the large number of participants, the jury was only satisfied with the projects depicting the municipality culture centres. The first and second prizes were shared equally by Henn Roopalu’s work “Agitator” and August Volberg’s and Peeter Tarvas’ work “Tuljak”. The successful facade and plan solutions of the works were highlighted. The third prize went to the project “200” by architect Ilmar Laasi. In the opinion of the jury, the concept designs of the village’s cultural centres were of a significantly weaker level, which is probably the reason why the first and third place were not awarded. The concept design “Accent” by August Volberg and Peeter Tarvas was recognized with the II prize. At that time, community and cultural centres played an important part in the country’s cultural policy, what happened in them was controlled by the ruling power and carried the Soviet ideology to a greater or lesser extent. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(klick on the picture to see more illustrations)

Veel: 1940s, architect: August Volberg, architect: Henn Roopalu, architect: Ilmar Laasi, architect: Peeter Tarvas

Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs building

Mart Port, Uno Tölpus, Raine Karp, Olga Kontšajeva, 1963. EAM 4.3.2

The 11-storey administrative building influenced by the American so-called International Style was completed in the Tallinn city centre in 1968. The symmetrical facade of the building is characterized by regular rows of ribbon windows and a vertical windowless central part, which was supposed to form the background for the statue that stood in front of the building. The building has a U-shaped ground plan. On the first floor of the office building is a spacious vestibule, the walls of the vestibule were covered with pink Cuban origin marble. The offices are located on the following floors, the utility rooms are on the top floor. Conference and meeting rooms are located in the wing buildings, there is a courtyard in the middle of the building parts. A broad hyperbolic paraboloid-shell made of reinforced concrete covers the large conference hall located in the left wing of the building. Due to the complex construction, the lights were installed on the walls of the room and the ceiling was covered by 60,000 empty sprat boxes. The oiled and round sprat boxes helped to diffuse and reflect the light directed at them and ensured good acoustics in the hall. The location of the building is also significant. The office building was built on the site of the Estonian Academy of Sciences, which was foreseen by 1948 Tallinn Cultural Centre design plan (architect Harald Arman), on the other side of the Theatre Square is the “Estonia” theatre – politics and power is facing culture and spirituality. Since the autumn of 1991, the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been operating in the former Estonian Communist Party Politburo building. The author of the drawings is Rein Kersten. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(klick on the picture to see more illustrations)

Veel: 1960s, architect: Mart Port, architect: Olga Kontšajeva, architect: Raine Karp, architect: Uno Tölpus

Sauna in Kobela

Toomas Rein, 1983. EAM 48.2.8

The Linda kolkhoz sauna, designed by architect Toomas Rein, is located in the small village of Kobela in Võru County and is one of the great examples of Estonian rural architecture. Articulated volumes, rounded corners and a red high pitched roof give character to the two-storey building, red wooden details on the windows and doors add contrast to the white facade. The sculptural exterior of the building is also reflected in the interior designed by interior architect Aulo Padar. On the first floor there was a common room with a fireplace, utility rooms and an indoor pool, on the second floor there was a sauna and laundry rooms. An indoor slide between the two floors led from the hot sauna to the cooling indoor pool. From the second floor there is also an access to the terrace of the building, from there a slide and stairs lead to the pond next to the sauna. During the renovation in the early 1990s, the function of some rooms changed and a club started to operate in the building – the indoor pool was covered with a floor and the indoor slide was demolished, the light shaft on the second floor and the glass roof were closed. The composition merges architecture, geometry and abstract painting – black and white architectural photos are arranged in a regular grid, the cross-section of the building and the ground plan are covered by a layer of gold paint and colour spots. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

Veel: 1980s, architect: Toomas Rein

The War of Independence monument competition work “Mälestis-ehis”

Edgar Johan Kuusik, 1931. EAM 7.1.76

The story of the monument begins in the 1920s, when the statue of Peter I standing on the Freedom Square was taken down (1922) and it was decided to erect a statue of the War of Independence in its place. The construction of the monument delayed, and instead a massive limestone memorial-mausoleum designed by Edgar Johan Kuusik was erected at the Defence Forces Cemetery (1928). At the end of 1930, when the competition for the construction of a War of Independence monument on Harjumäe was announced, Edgar Johan Kuusik in cooperation with Elmar Lohk submitted two works for the competition. The competition entry with the keyword “Mälestis-ehis” repeats the same motif as the memorial-mausoleum in the cemetery – a massive cubic volume with four arches opening towards the four cardinal directions. However, the prize went to the authors’ second work “Pro Patria”. Later, Kuusik used the same style at the gate building of the Defence Forces Cemetery (1938). The competition work “Mälestis-ehis” was donated to the museum by the E. J. Kuusik family in 2021, the drawings were conserved in Conservation and Digitisation Centre Kanut. Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1930s, architect: Edgar Johan Kuusik

Villa Tammekann in Tartu

Alvar Aalto, 1932. Maquette: Peet Veimer. EAM MK 47

February 3 is the 125th anniversary of the birth of the world-famous Finnish architect Alvar Aalto. The private residence of the University of Tartu professor August Tammekann at Kreutzwaldi st. 6 Tartu is the only completed building in Estonia designed by architect Aalto. The flat roofed, two-storey functionalist building was partially completed in 1933. According to the style’s principles, the building’s facade reflects the usage of the interior spaces. On the street side, a stairwell rises behind the vertical window, on the courtyard side, the central element is the wide ribbon window of the living room with a fireplace located at the bottom of the window. The flat roof of the house, which was not widespread at the time, caused a lot of discussion among the locals and was even considered as an anti-God phenomenon. The villa was rebuilt into an apartment building during the Soviet period. In 1994, the building was returned to Professor Tammekann’s offspring, in the 1998 University of Turku bought the building. The villa was restored according to Alvar Aalto’s project in 2000. Today, the Granö Centre of the universities of Turku and Tartu is located in the building.

The maquette of Villa Tammekann was made for the Estonian Architecture Museum exhibition “Aalto: three projects in Estonia” by Peet Veimer in 1998. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

Veel: 1930s, architect: Alvar Aalto

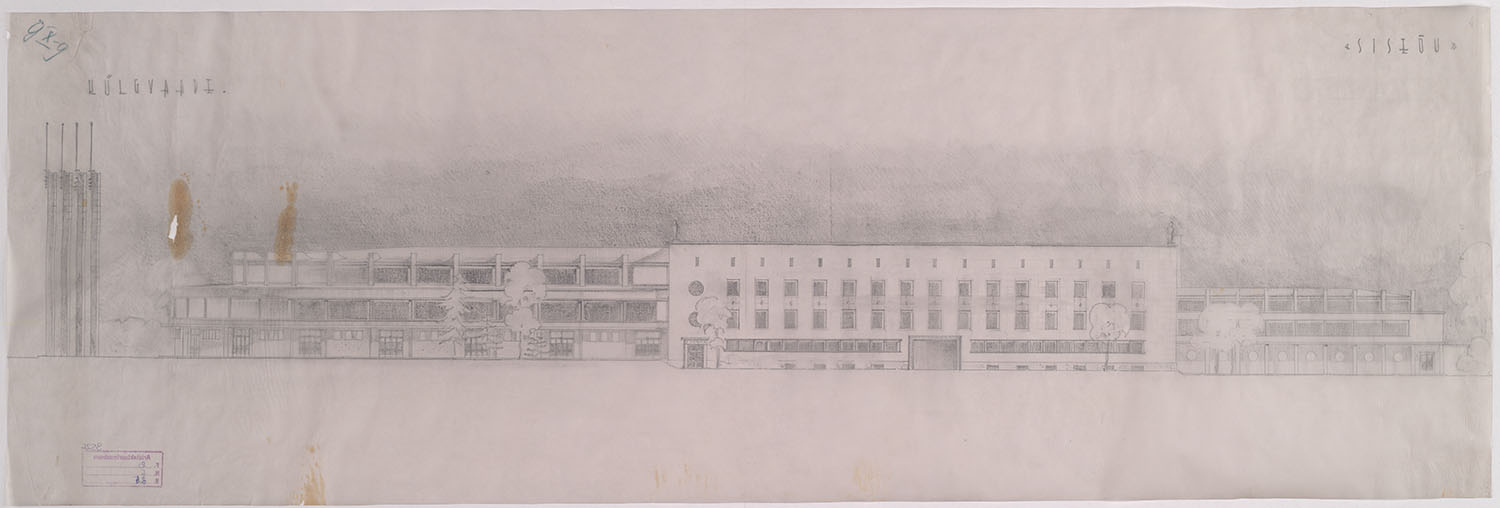

The competition project of physical culture centre “Siseõu”. II prize

Erika Nõva, 1939. EAM 2.6.34

Sports and physical culture become the keywords of modern life in the mid-1930s. Planning a representative sports building in Tallinn become on the agenda. A suitable location was found in the Falkpark (today Falgi Park) located at Toompuiestee. In November 1938, the architectural competition was announced. The plan was grandiose: the building had to hold a main hall (20×40 m) for gymnastics, basketball and volleyball, tennis, wrestling, weightlifting and other fields. The stands had seats for 4,500 spectators. Another large room group consisted of a swimming pool (14×25 m) and two saunas, and the third was a gymnasium. In addition to training, dressing and washrooms, office spaces and apartments for officials were also planned. The international competition ended in April 1939. Finnish architects Enn Muistre and Einar Teräsvirta won the first prize, the third prize went to Latvian architect Arturs Reinfelds. Erika Nõva, one of the first female architects in Estonia, received the second prize. The award committee highlighted Nõva’s urban-planningly successful solution “… because the semicircular forms relate architecturally well to multi-directional streets.” The solution of the main hall, the swimming pool and the central part of the building was called magnificent / Eesti Arhitektuur. Varamu arhitektuuri osakond nr 3, 1939/. Erika Nõva recalls: “This job started to bother me. I thought I don’t deserve it, but I couldn’t give up the thought either. Little by little, I began to observe related examples from foreign magazines and tried to sketch it according to the program. When I showed these sketches to Kotli and Soans /… /, they encouraged me to continue working.” / Erika Nõva. Minu töö ja elu. Tallinn, 2006, p. 61/. What follows is a long and cheerful description of the work-hours at night, the draftsman’s assistant Tsinovski (Nopski), the nerve-wracking moments when sending off the work at the post office of Nõmme station, the victory celebration at the “Ehitaja” office and later at Mustamäe’s home. Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1930s, architect: Erika Nõva

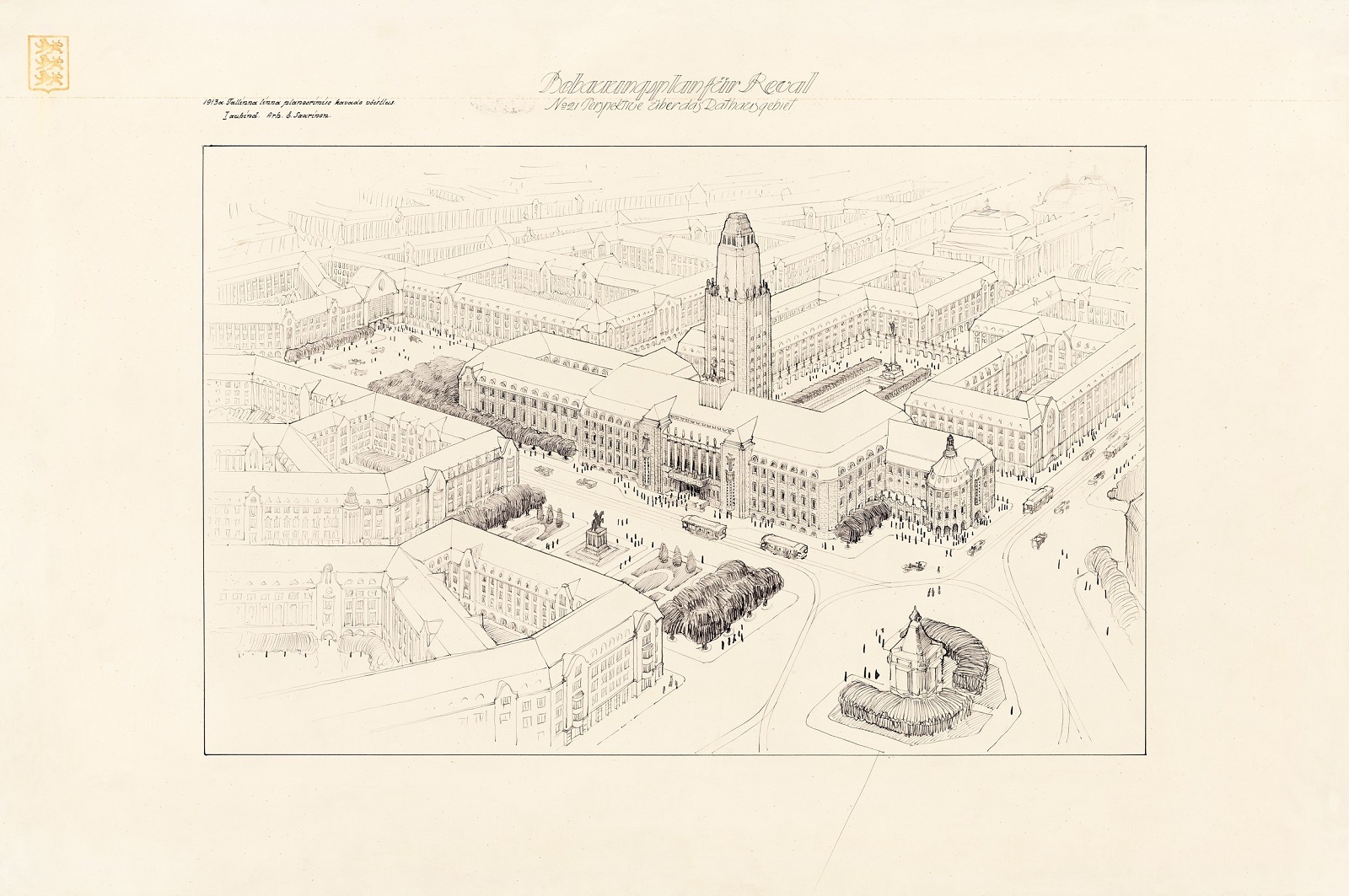

“Suur-Tallinn” (Greater-Tallinn) master plan

Eliel Saarinen, 1913. EAM 1.1.8

In the early 20th century, Tallinn was transforming from a sleepy provincial resort town into a modern, mid-sized European city. Rapidly developing industry and population growth resulted in the need to give consideration to the city as a comprehensive system. Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen had already worked with plans for developing Budapest, Helsinki, and Canberra. Thus, his first-place prize in the 1912–1913 competition for a general plan of Tallinn was somewhat expected. Saarinen’s entry is monumental: the city centre would be stocked with six-storey stone buildings, while worker-class neighbourhoods would be reformed with row-houses. This year is the 150th anniversary of the birth of architect Eliel Saarinen. The drawings, which belonged to the Tallinn City Government for a long time, were recently given to the museum.

Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1910s, architect: Eliel Saarinen

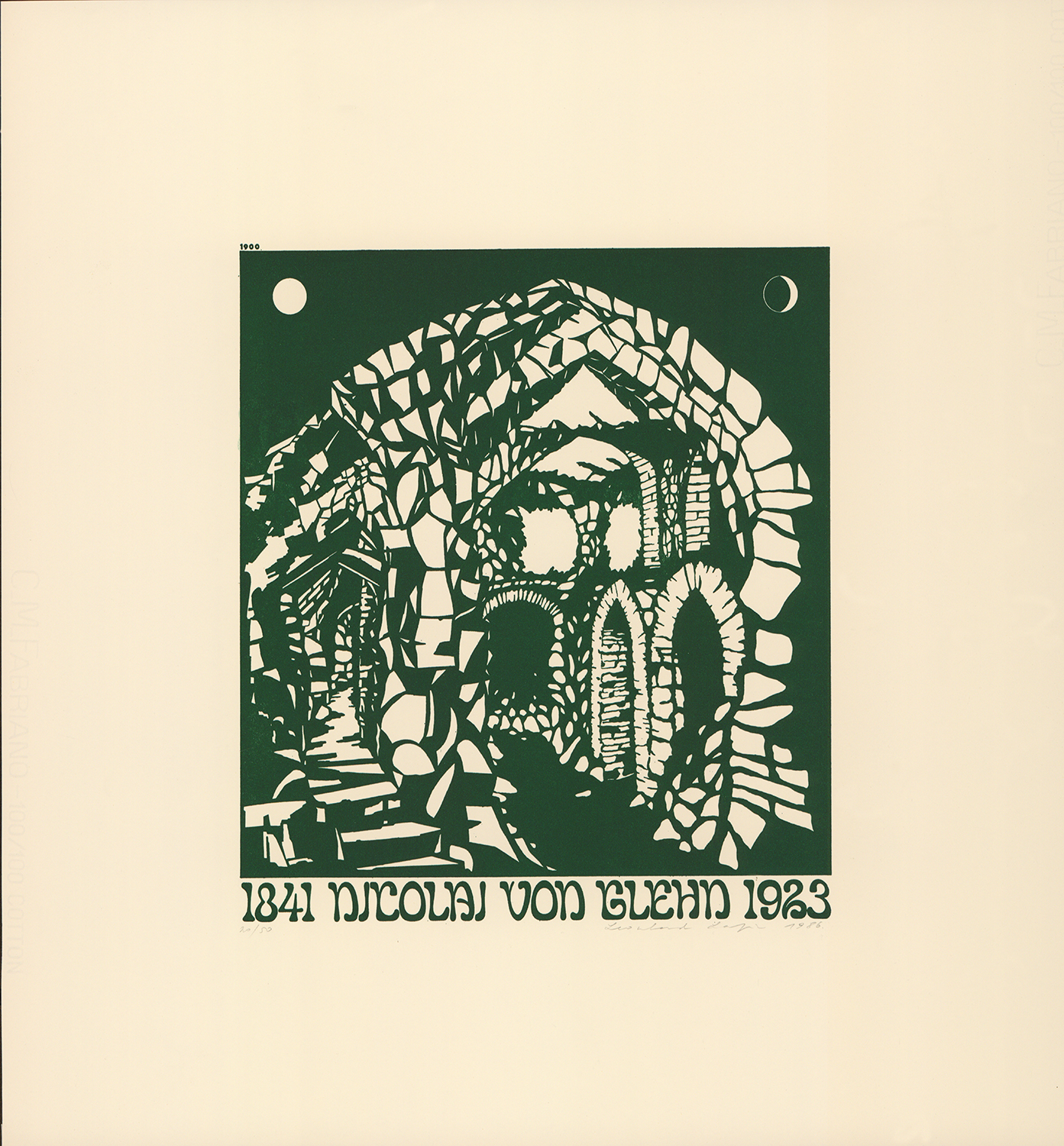

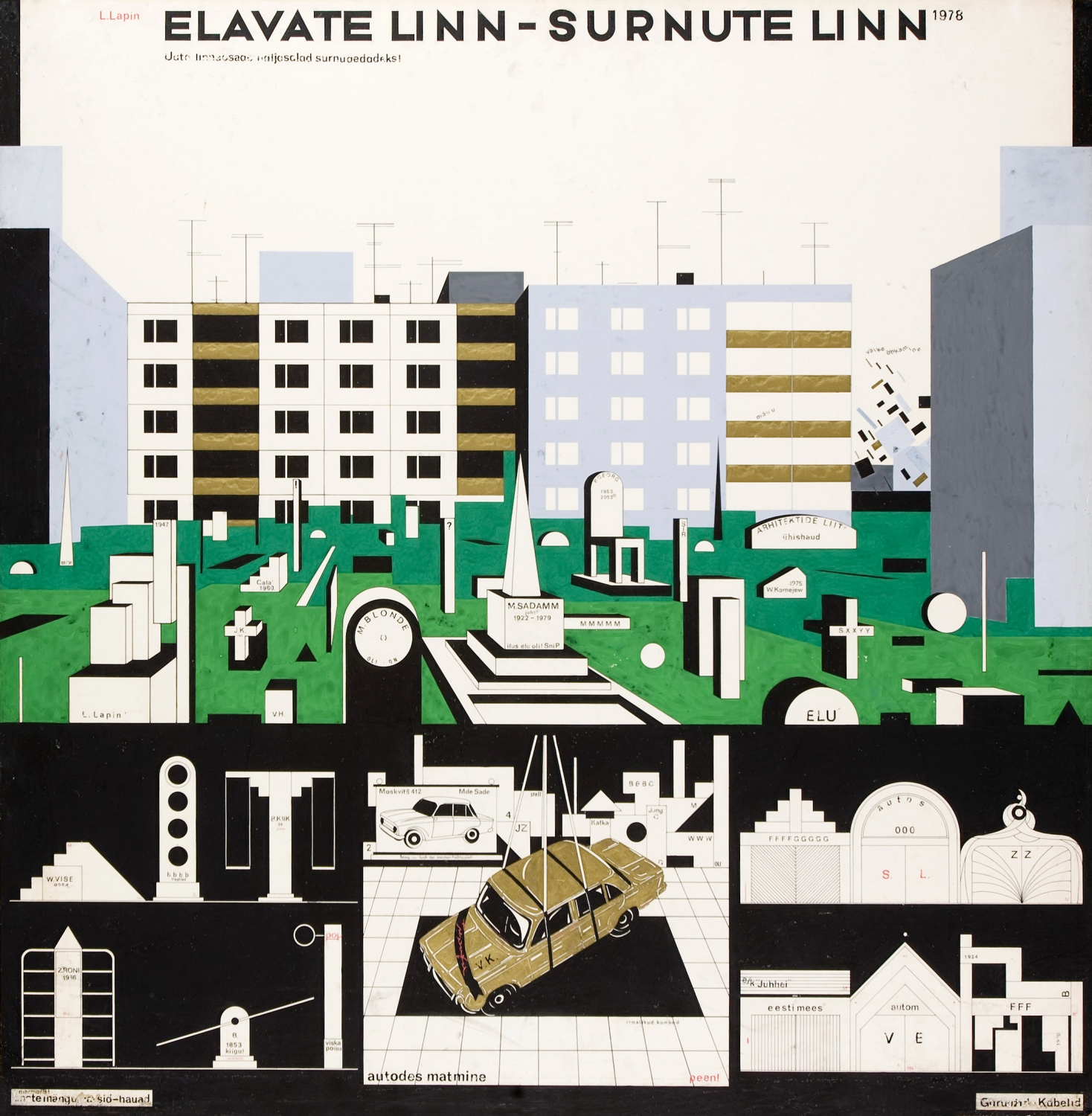

Graphic series “Estonian Art of Architecture”

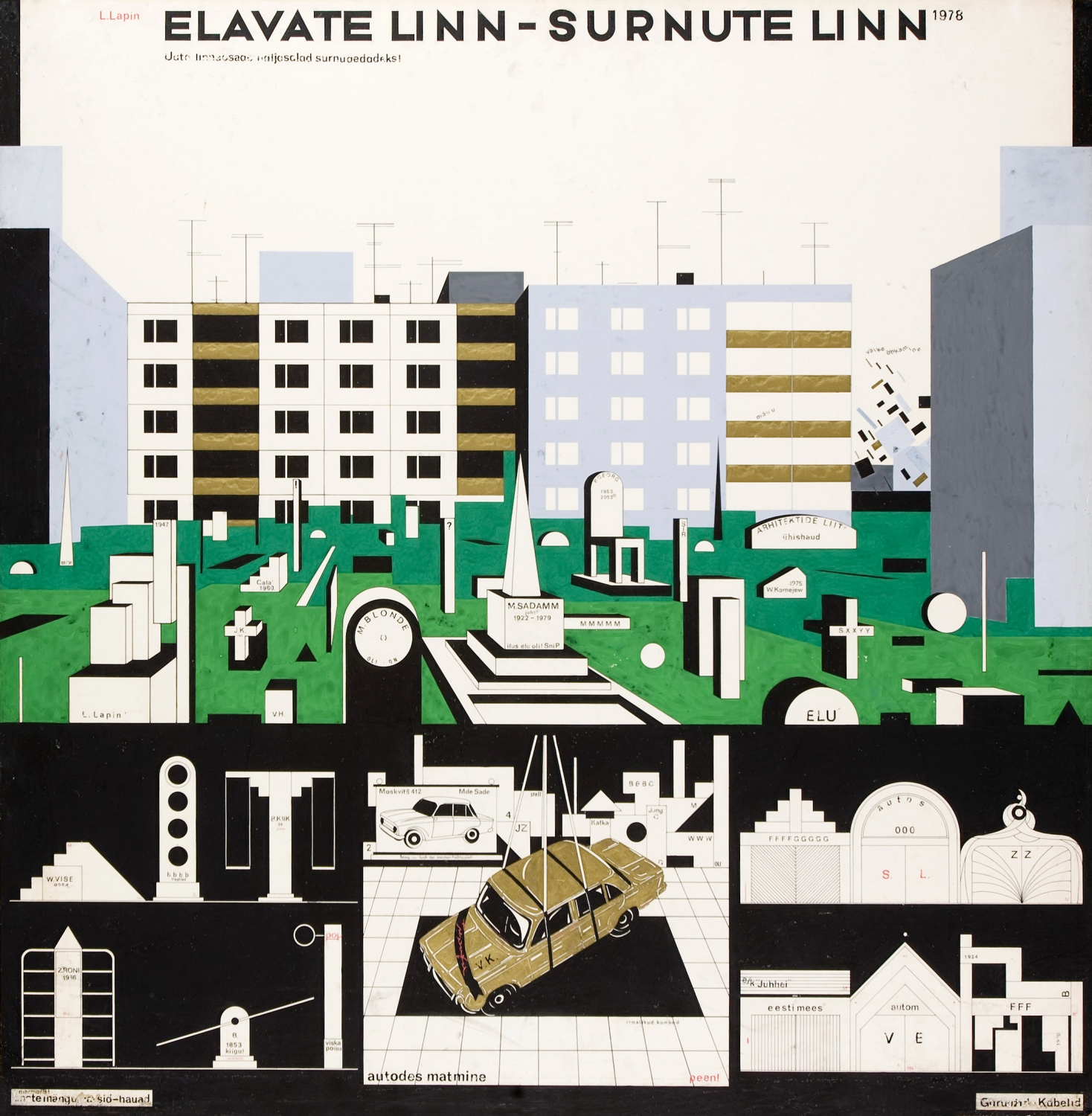

Leonhard Lapin, 1986–1988. EAM fond 68

On December 29, Leonhard Lapin would have celebrated his 75th birthday. Lapin’s legacy is characterized by bold modernist architecture, but his work was far from limited to that. Leonhard Lapin has published poetry collections and was an outstanding art innovator. Recognizable are his pop-art-influenced graphics, distinctive architecture in urban spaces and art galleries. Leonhard Lapin has kindly brought his projects and works of art to the architecture museum over the years. This year, the architectural drawings in the home archive arrived here with his legacy. As a heartfelt addition, Leonhard Lapin’s son and daughter gave the museum 5 colorful letterpress graphics from the 1980s. The series is called “Estonian Art of Architecture” and depicts the work of various masters from the early decades of the 20th century: Nikolai von Glehn’s Palm House, Georg Hellat’s Art Nouveau old Endla theater-society house, National Romantic Kalevi Yacht Club Pirital (Karl Burman), Herbert Johanson and Eugen Habermann’s Riigikogu building and Tallinn 21. School designed by Artur Perna. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1980s, architect: Leonhard Lapin

Lantern drawing of the President’s Office

Alar Kotli, 1938. EAM 2.9.2

The main entrance of the President’s Office is flanked by lanterns featuring abundant rosettes and leaf motifs which comprise an integral whole with the Neo-Baroque architecture. Seeing as this is a representative building, there are sockets for flag poles above the lanterns. The drawing also depicts a familiar motif from the coat of arms of Estonia – a bronze leopard (by sculptor Voldemar Mellik) set to guard the doorway on both sides. This pencil drawing was part of the colletion given to the museum in 1993 via firm Eesti Ehitusmälestised. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1930s, architect: Alar Kotli

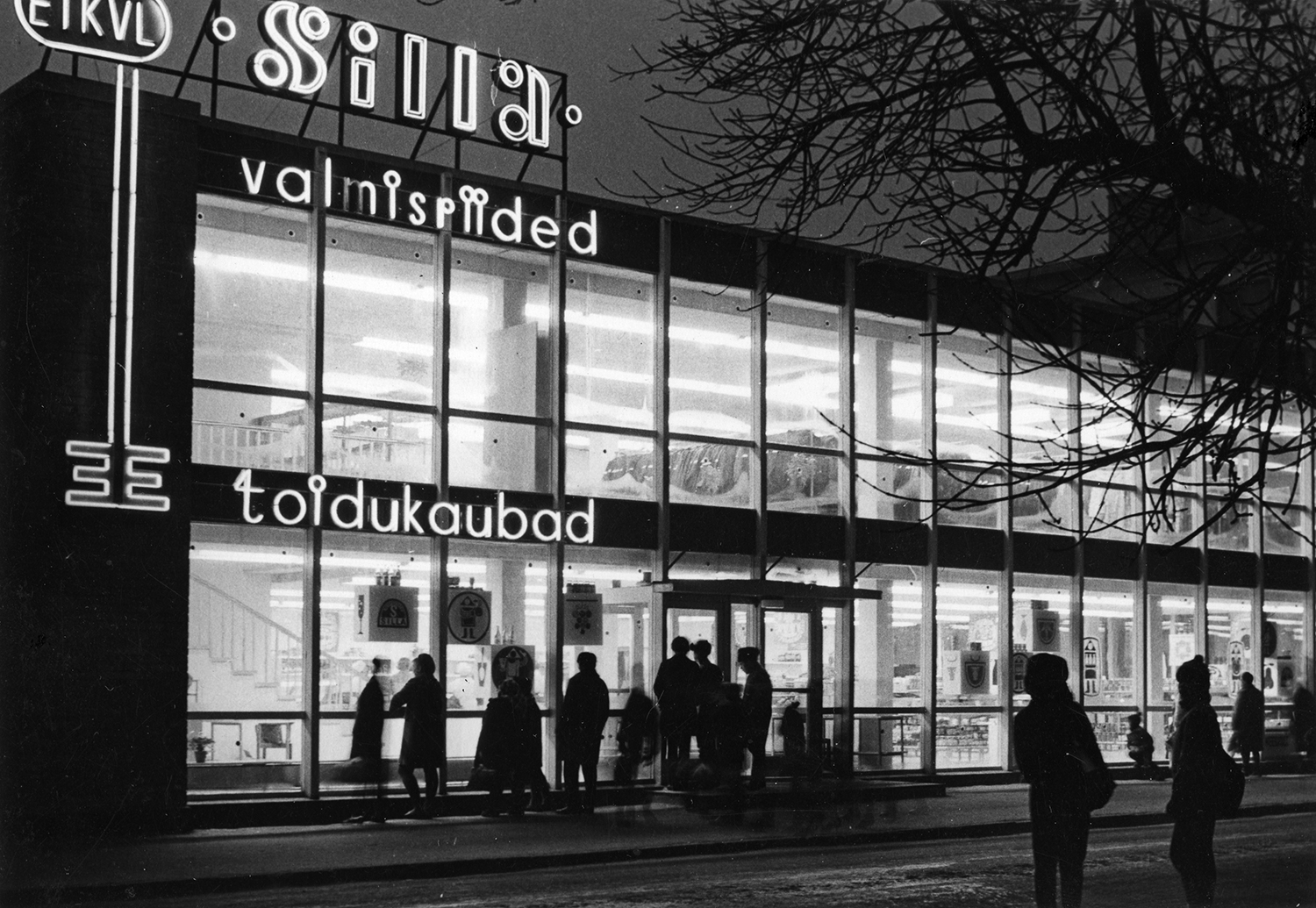

Shop “Silla” in Pärnu

Rein Heiduk, 1964. EAM 6.4.7:76. Photo: Rein Vainküla

In 1968, a newly opened shop designed by Rein Heiduk on Silla street in Pärnu attracted the attention of passers-by with a modern look. Reminiscent of a glass pavilion, the store “Silla” hid food products on the first floor and industrial goods on the second floor. When writing about the architecture of the building, the architectural historian Leonid Volkov has referred to its connections with both the international style and the constructivism of the 1920s (L. Volkov’s manuscript “Eesti arhitektuur 1940-1989. Part II, p. 103). The Estonian Consumers’ Cooperative Union (ETKVL) was responsible for the fresh production of the store network that consolidated the pan-Estonian trade network and, for example, opened the Tapa department store, which was also designed by Rein Heiduk (1966). In 1994, Leonid Volkov’s wife Helga Volkov handed over a manuscript dedicated to Estonian architecture to the museum along with a rich photo collection. The house was photographed by Rein Vainküla. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1960s, architect: Rein Heiduk, Pärnu

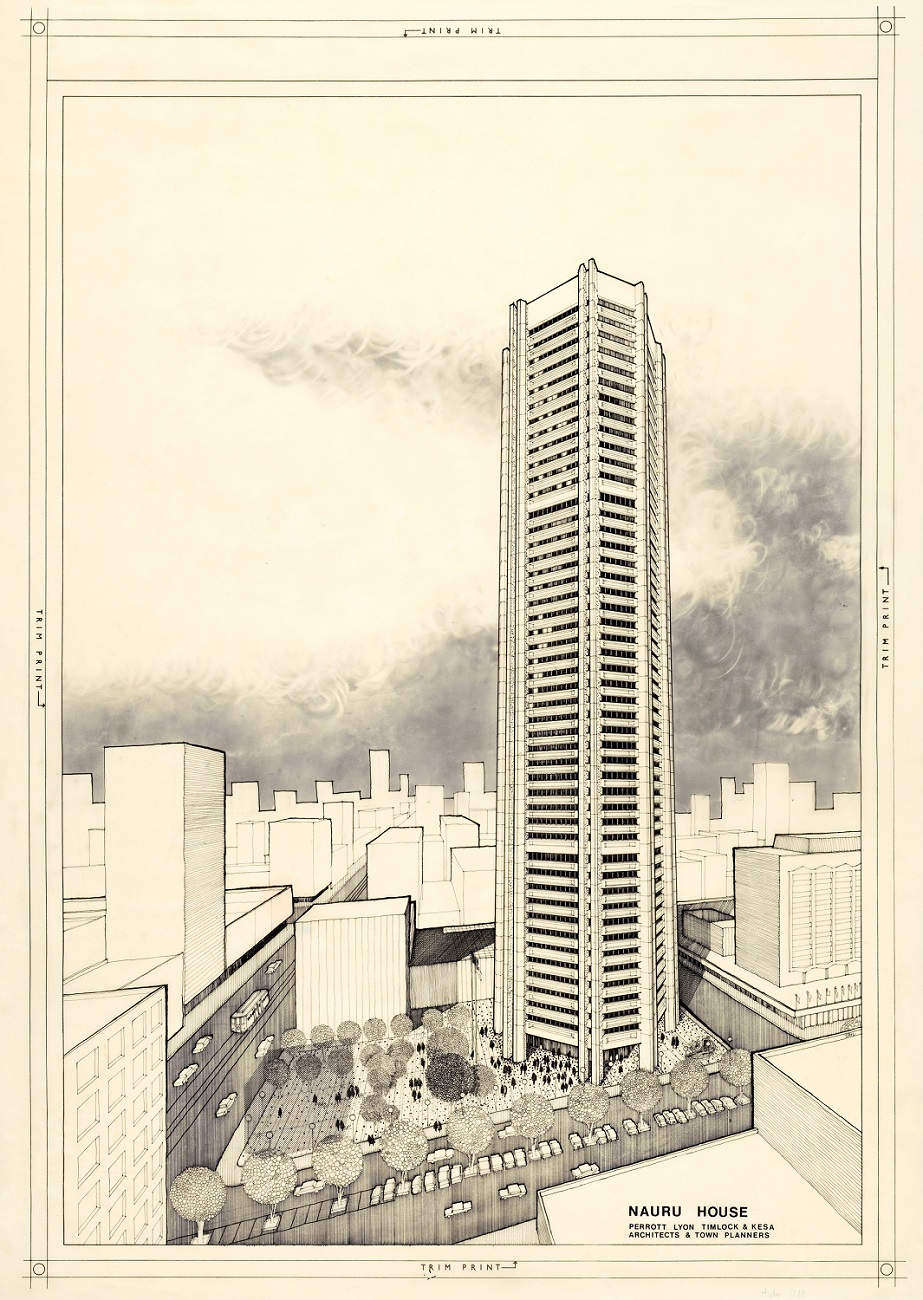

Bus Terminal in Caracas

Oscar Tenreiro, 1976–1977. EAM fond 70

The giant bus terminal in Caracas was the first collaborative project of Estonian-born engineer August Komenant and Venezuelan architect Oscar Tenreiro. In an interview with the architectural historian Carl-Dag Lige, Tenreiro told the story of how it came about: “How did Dr. Komendant come to the fore? I had seen and partly read his book 18 years with the architect Louis I. Kahn. Why? Because Louis Kahn was very renowned in the world. I also came across a book review, which began with a paraphrase: “No architect is a hero in the eyes of his engineer”. I read the book and told myself that I need such a man for my project. It was the Caracas bus terminal…” (Civil engineer August Komendant, Compiler Carl-Dag Lige, Estonian Museum of Architecture 2022, page 87).

The 9 original drawings of the Caracas Bus Terminal, together with the drawings of the Plaza Bicentenario square and the planned Venezuelan National Gallery GAN were donated by the renowned architect to Estonian Museum of Architecture in January 2020. The drawings by Oscar Tenreiro and nearly a few hundred photos will be an addition to the new archive fond of engineer August Komendant. Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1970s

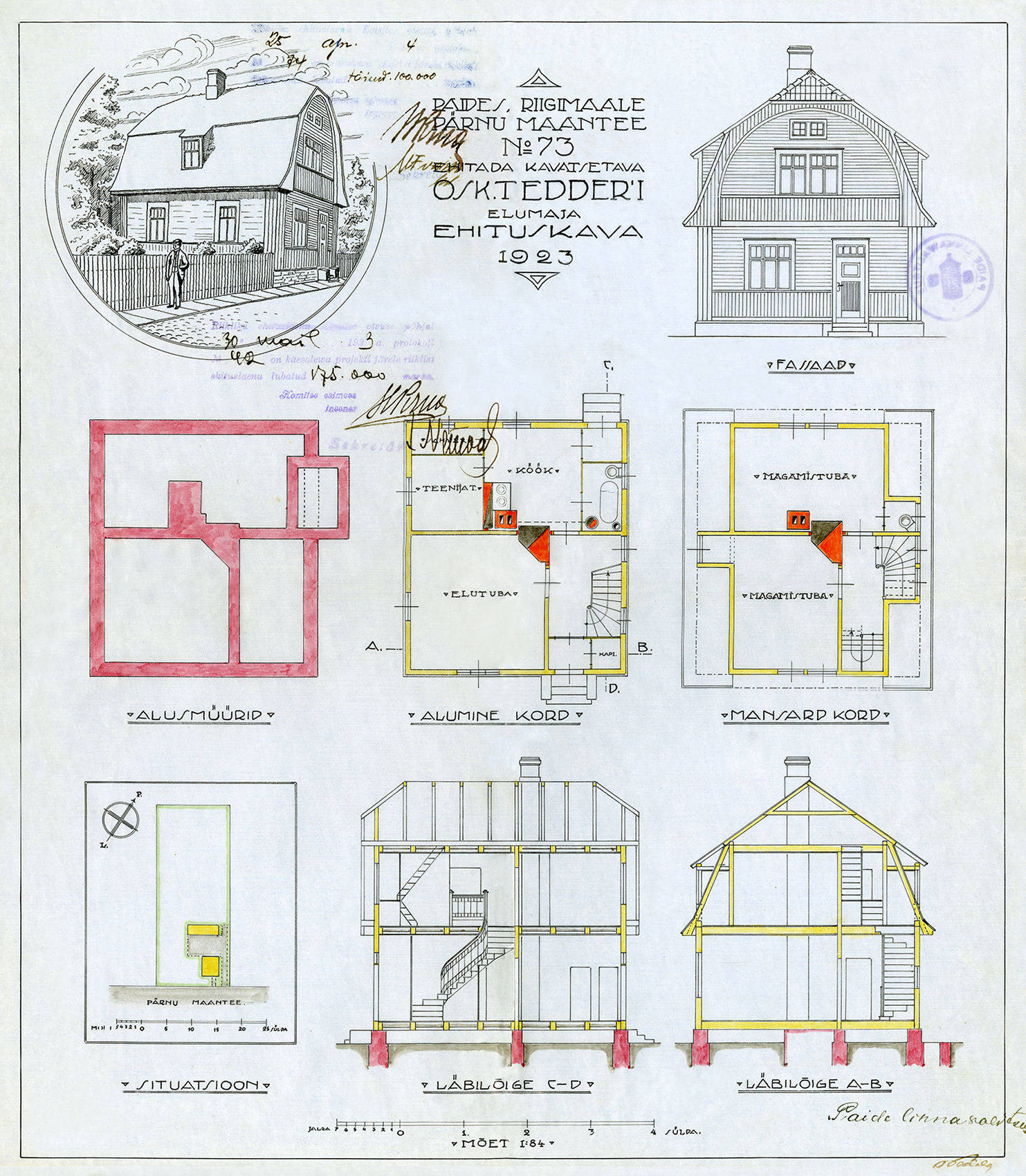

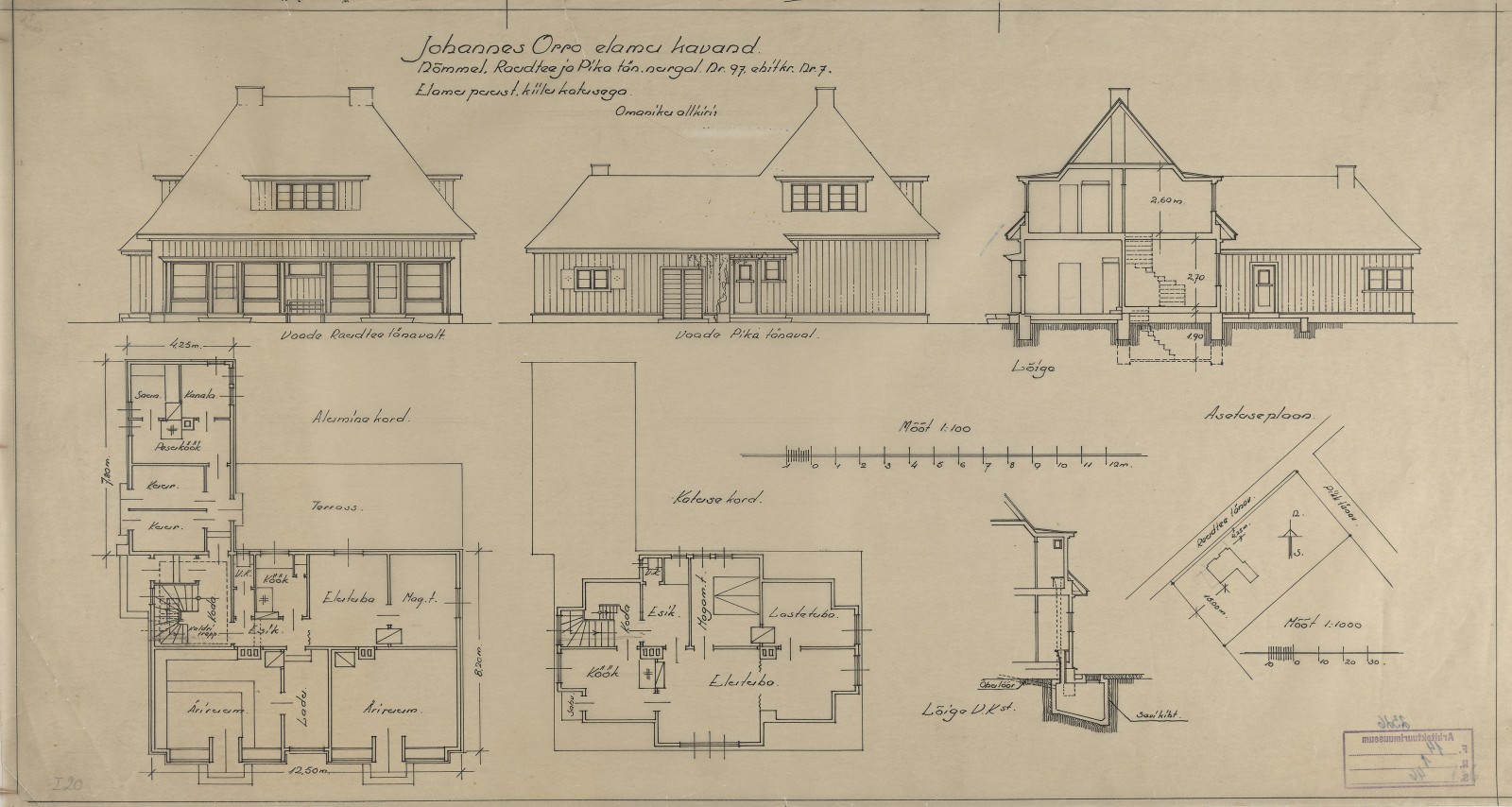

House in Paide

It was not overly common to commission house designs from a professional architect in the early 1920s, especially in towns and boroughs – designs were often made by building technicians and civil engineers. Compared to nowadays, the project seems unusually compact. One sheet would feature all the information about the house: views, floor plans, sections […]

It was not overly common to commission house designs from a professional architect in the early 1920s, especially in towns and boroughs – designs were often made by building technicians and civil engineers. Compared to nowadays, the project seems unusually compact. One sheet would feature all the information about the house: views, floor plans, sections and every now and then a perspective view to please the client and show the general appearance of the future house. The house of Oskar Tedder who commissioned the project to acquire the building loan, was constructed on one of the main streets of Paide where the state handed out empty plots to establish a new garden city-like housing area. The project made in ink on the drafting cloth was added to the museum’s collection in 1992. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1920s, dwelling

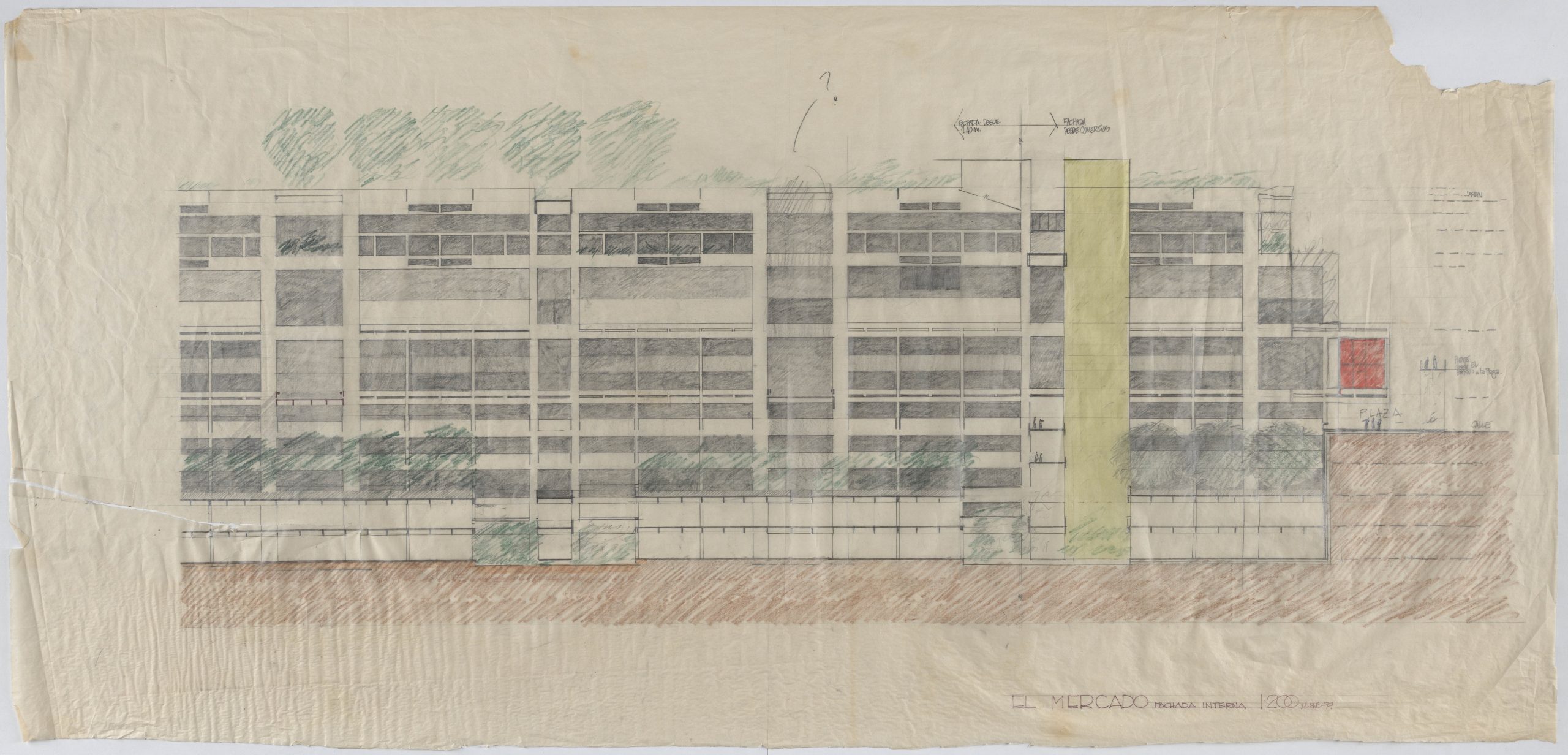

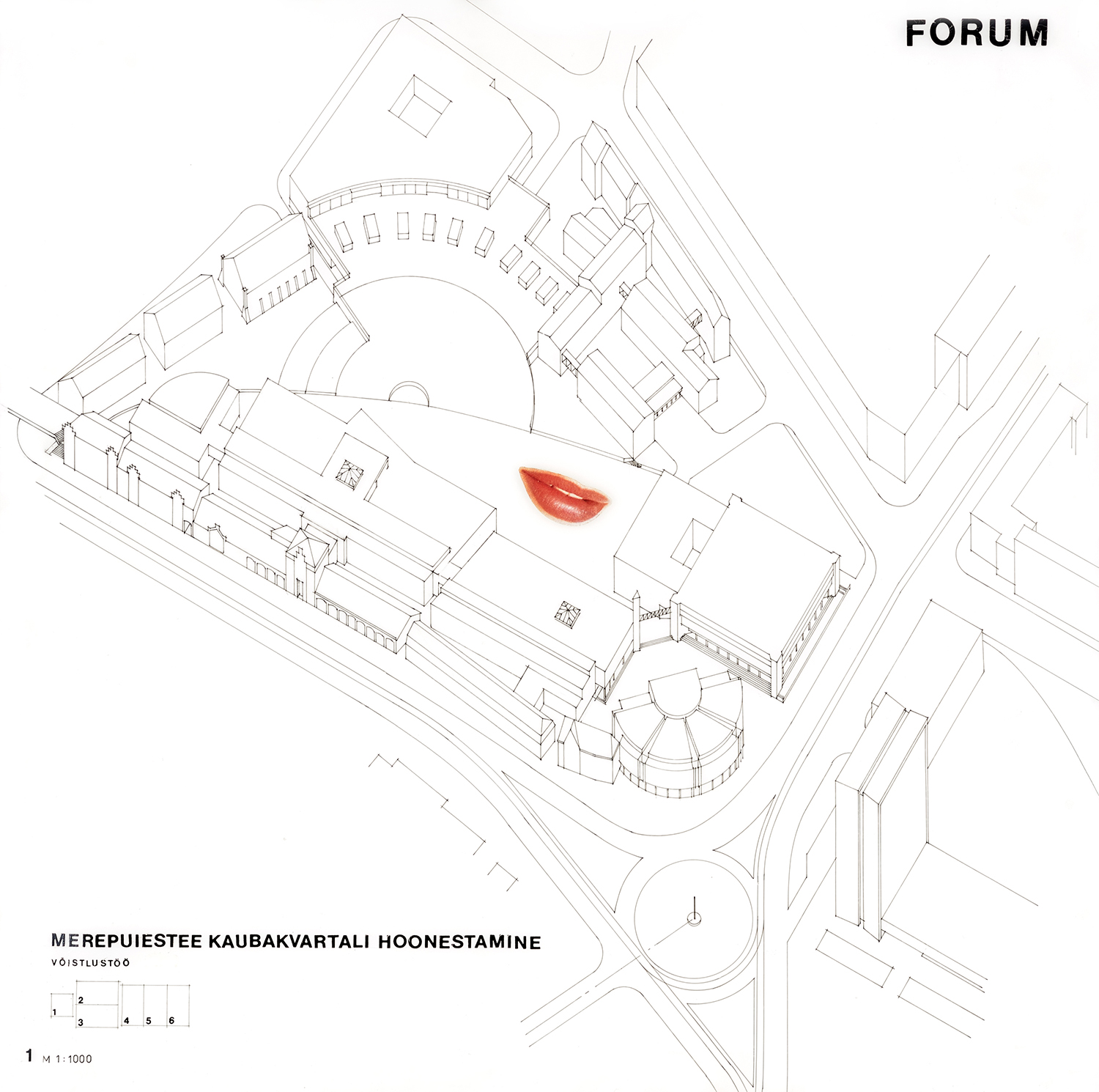

Competition entry for the shopping centre at Mere Boulevard in Tallinn

Tiina Tallinn, Ell Väärtnõu, Arvi Aasmaa, engineer Rein Karilaid, 1989. EAM 5.1.21

Up until now the factory premises of the Rotermann Quarter had been closed off and an architectural competition was organised to find a way to better incorporate the area into the urban landscape. The quarter was to be the main commercial and service centre of Tallinn. The centre of the competition entry titled “Foorum” is a crescent market square – a modern interpretation of the historic forum in ancient Rome, together with all the surrounding market pavilions. The idea of market as a place of communication is further emphasised by a collage detail of lips as a means of communication. The competition entries were given to the museum in 1993 by the Tallinn City Office. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1980s, architect: Arvi Aasmaa, architect: Ell Väärtnõu, architekt: Tiina Tallinn, engineer: Rein Karilaid

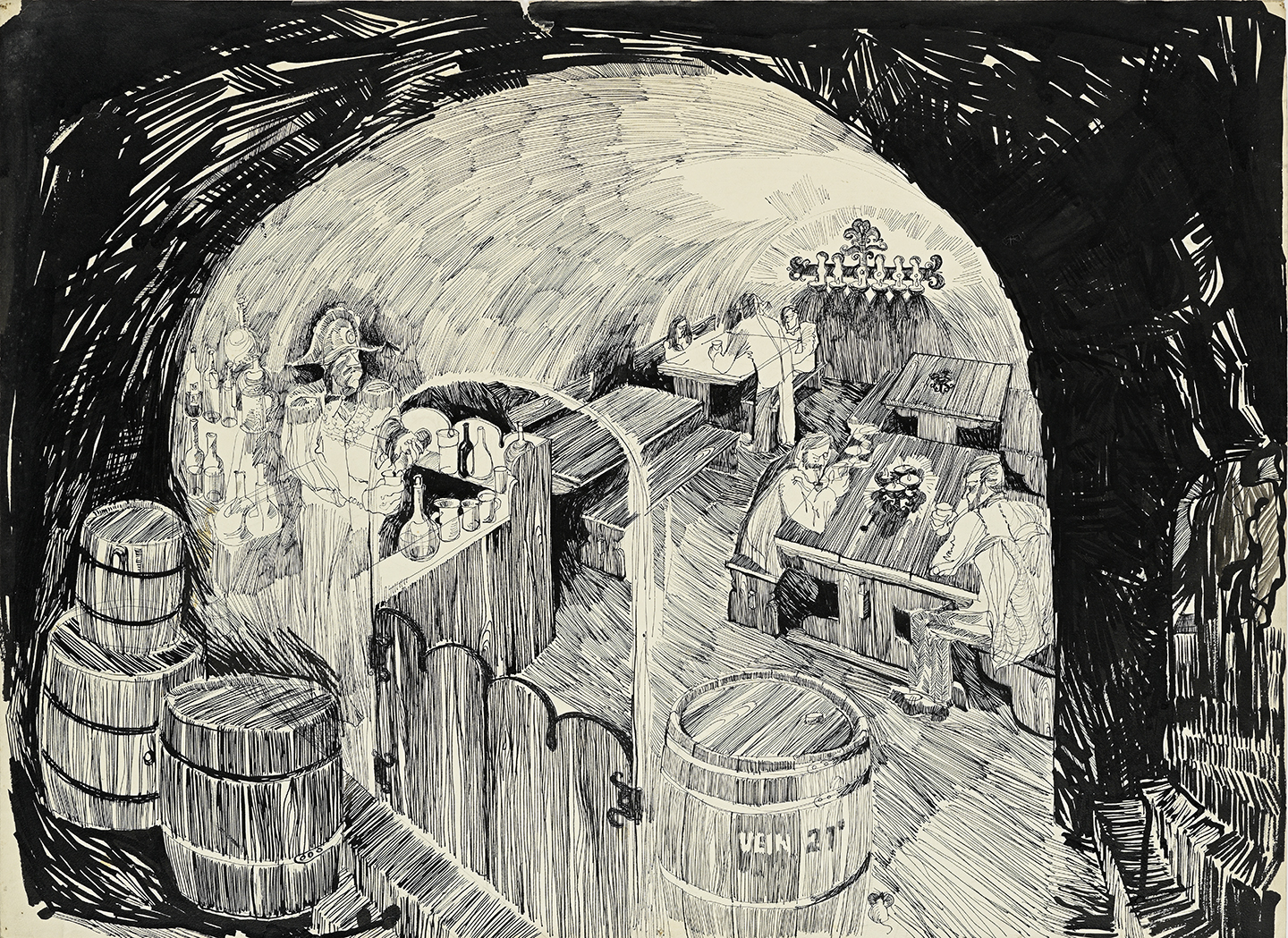

Café Neitsitorn (Maiden Tower)

Interior architect Aala Buldas, 1970–1980. EAM 4.7.17

One of the most unique defensive towers of the Tallinn city wall, the quadrilateral Neitsitorn (Maiden Tower) was restored in the 1970s. The Maiden Tower together with Kiek in de Kök were defensive structures of crucial importance in the defense of medieval Tallinn. However, after the loss of the status of Tallinn as a fortress city, the centuries-long defense function of the wall towers changed, and in the 19th century the wall towers were rebuilt into dwellings, as did the Maiden Tower. The two-storey residential building became a home for renowned artists and writers, whose apartments had several studio rooms. In the early 1970s, field research on the Tallitorn (Stable Tower) and the Maiden Tower began in order to find a public function for the building. The work was encouraged by the forthcoming Olympic regatta. During the reconstruction of the Maiden Tower, about half of the structure was rebuilt almost as new. The building was given a new floor, underground utility rooms and an impressive glass wall on the Old Town side. The Café Neitsitorn was situated in the new premises, which opened its doors to the public in 1980 and immediately became a big hit. The authors of the tower’s reconstruction design were an architect Tiina Linna, an art historian Villem Raam, and the café’s interior design was made by Aala Buldas. In 2022, the drawings were donated to the museum by Eva Mölder from the restoration company Vana Tallinn. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1970s, interior design architect: Aala Buldas, reconstruction

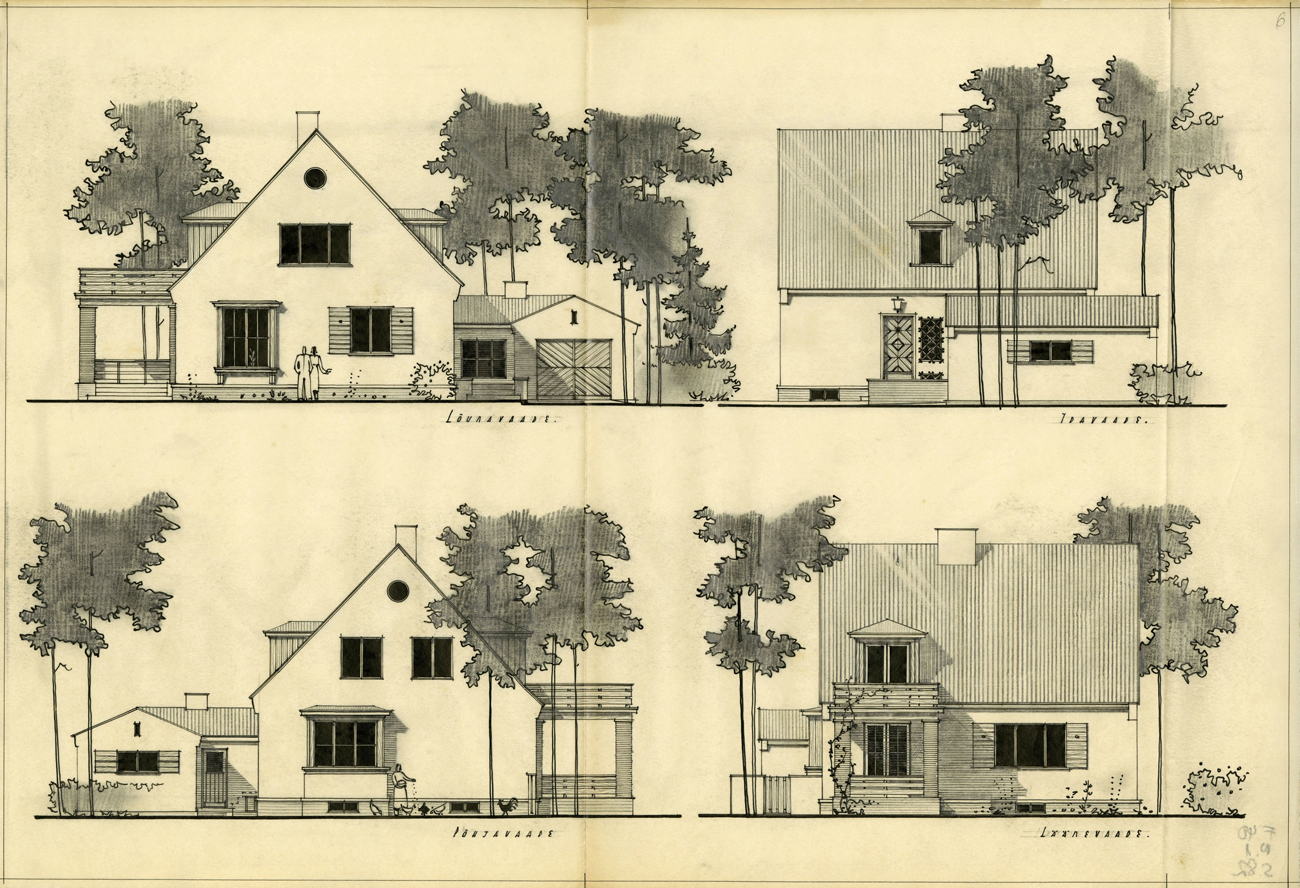

Hanko’s house in Tartu County

Karl Burman senior, 1922. EAM 2.2.695

The drawing depicts a dwelling in a farm in Kambja owned by journalist and entrepreneur August Hanko. At the time, Karl Burman favoured National Romanticism and drew inspiration from traditional Estonian farm architecture, using poetic elements to mitigate its practical nature. Burman’s oeuvre includes repeated elements in the form of bay windows, porches and a high-hipped thatched roof. Small grid windows of different sizes and shapes are also common to his work. As is characteristic to the style, Burman avoided excess practicality in the arrangement of space, placing a spacious hall in the centre of the layout and the living quarters surrounding it. The project was never realised. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1920s, architect: Karl Burman

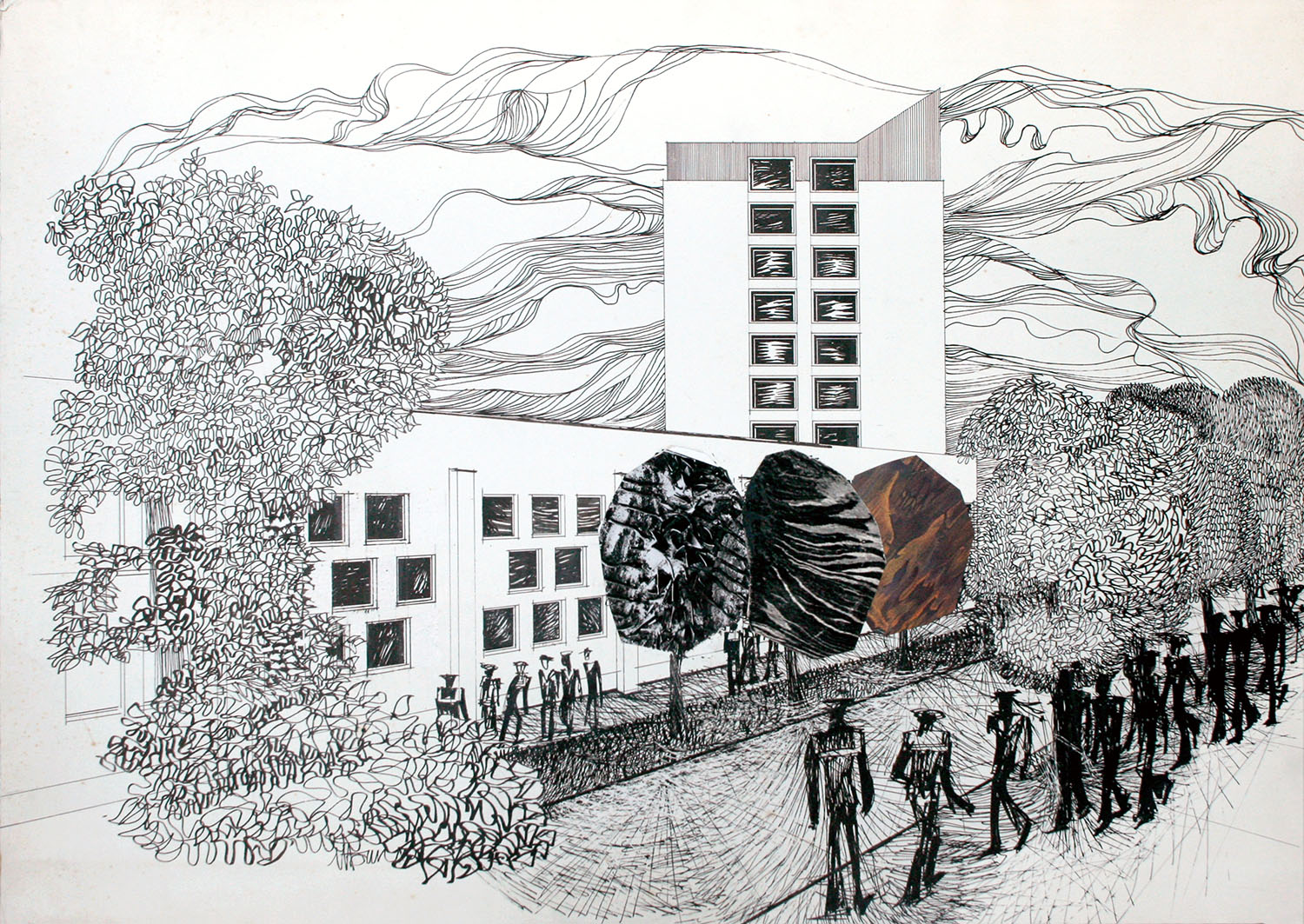

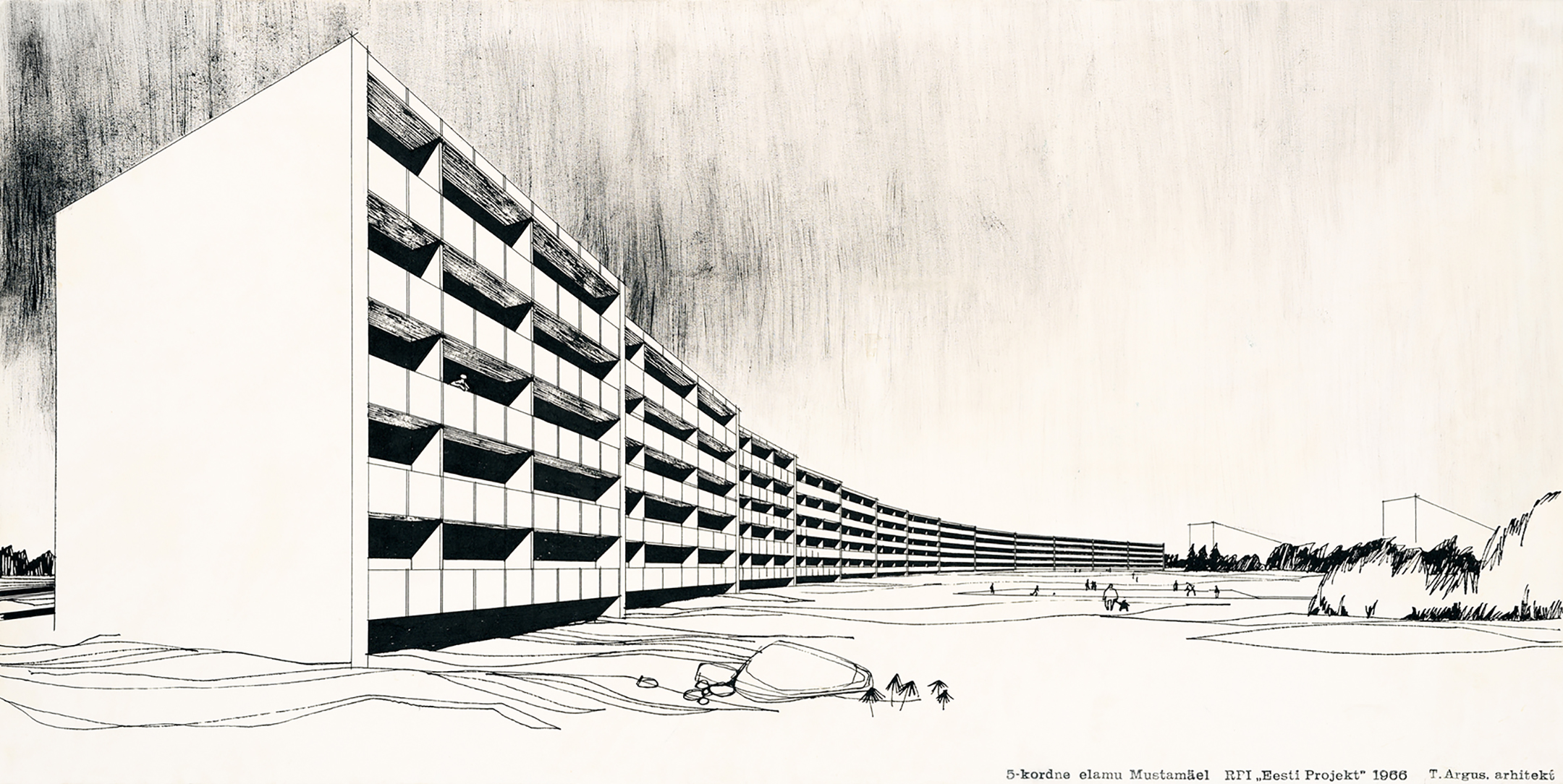

Five-storey apartment building in Mustamäe, Tallinn

Tiiu Argus, 1966. EAM 4.2.3

The Mustamäe district, which was erected in Tallinn in the 1960s, was divided up into microdistricts that were designed to accommodate 6,000–10,000 residents. The monolithic form of the panel apartment blocks designed for the second microdistrict is based on the development of prefabricated panels, permitting the construction of buildings with five or more storeys, not just four storeys like before. In the context of the depreciated housing options at the time and before the microdistricts became dormitory suburbs, the first panel apartment blocks that dominated the landscape looked innovative. They were thought to display a community effect and bring neighbours closer together. This ink drawing was given to the museum by design office Eesti Projekt in 1992. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1960s, architect: Tiiu Argus

Visions of Tallinn Olympic Sailing Center

Mart Port, 1972–1973. EAM 52.4.2

Major design work preceded the sailing regatta of the 1980 Olympic Games in Tallinn. The Pirita estuary was redesigned to serve the public and sailors. As the local architects had little experience in creating a building complex that meets the requirements of the Olympic Games, the then city architect Dmitri Bruns decided to travel to Kiel, Germany, where the 1972 Olympic regatta was held, together with Mart Port, chief architect of the Estonian Project, and Urmo Kala, deputy chairman of the sports committee. There, with the kind assistance of the German colleagues the group got acquainted with the construction of the Olympic Sailing Center in Schilksee. The knowledge gained allowed us to announce an architectural competition in 1973 to find a project for the Pirita Sailing Center in which 12 works were submitted. The accompanying visualization comes from an album of Mart Port’s works and was probably part of a set of projects submitted to the competition but not awarded. The hotel has a hotel-bar-restaurant for athletes and guests at the forefront, and of course the Olympic light tower is centrally located in the complex. Like the Schilksee sailing center, the buildings have been built in stages. While in the lower picture the pier edge is used by holidaymakers, in the upper picture the tone is set by cars, which are probably influenced by Western magazines. The design features modern American cars, including the sporty-looking Dodge Challenger. The album was donated to the museum by Heldi Toom in 2014. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1970s, architect: Mart Port

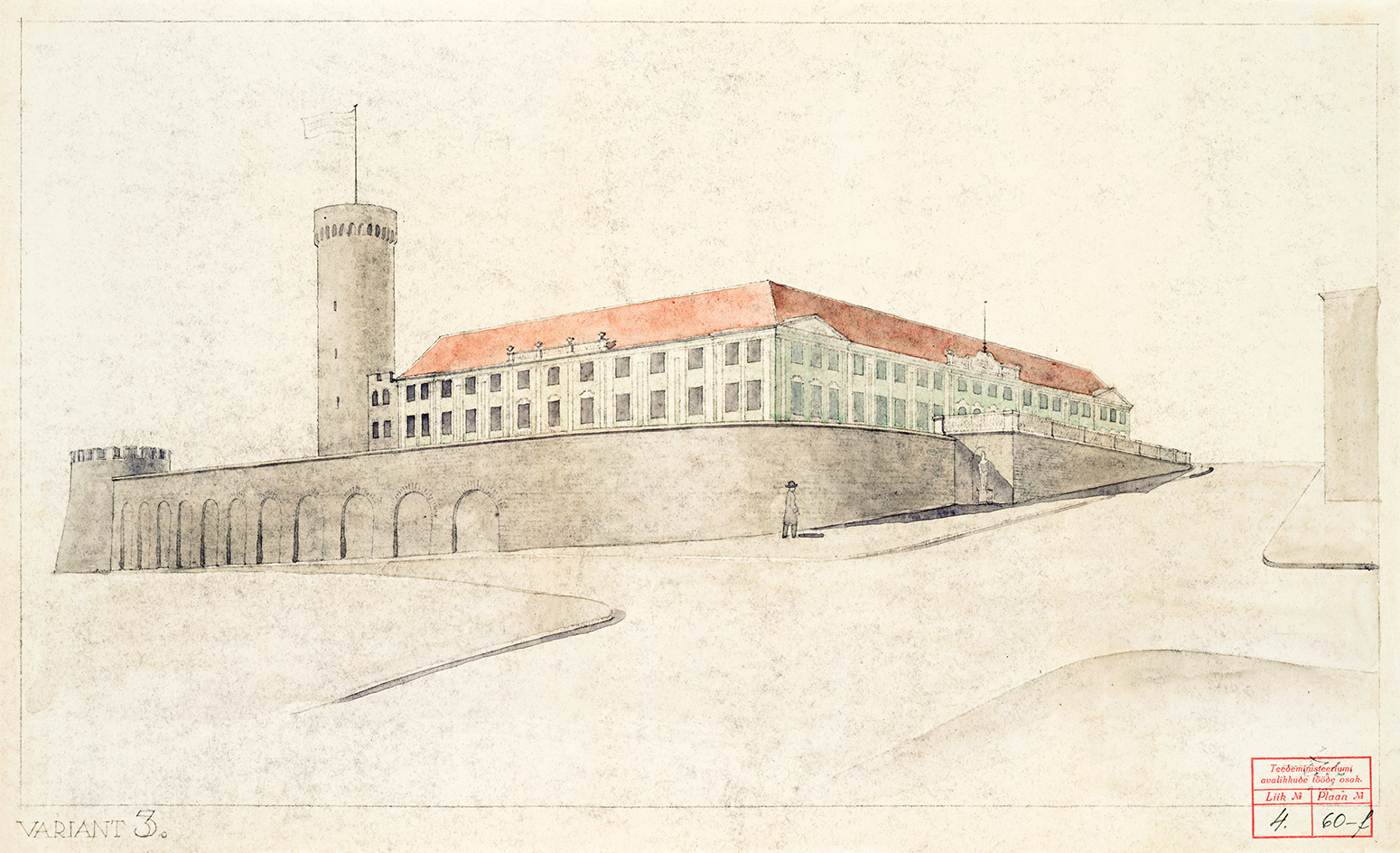

Reconstruction of the Toompea Castle and the castle garden

Alar Kotli, 1933–1936. EAM 2.11.15

The aspiration for representability that began in the second half of the 1930s made its way to architecture via state buildings, manifesting in the use of traditional forms and details. The Estonian government, which had centred around Toompea, reconstructed the southern wing of Toompea Castle and the Governor’s Garden in front of it, opting for a Neo-Baroque style that harmonised with the 18th-century Late Baroque look of the front of the castle. The supporting wall of the Governor’s Garden also received a fresh look. The Coloured copy in watercolour technique was added to the museum collection in 1991. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1930s, architect: Alar Kotli

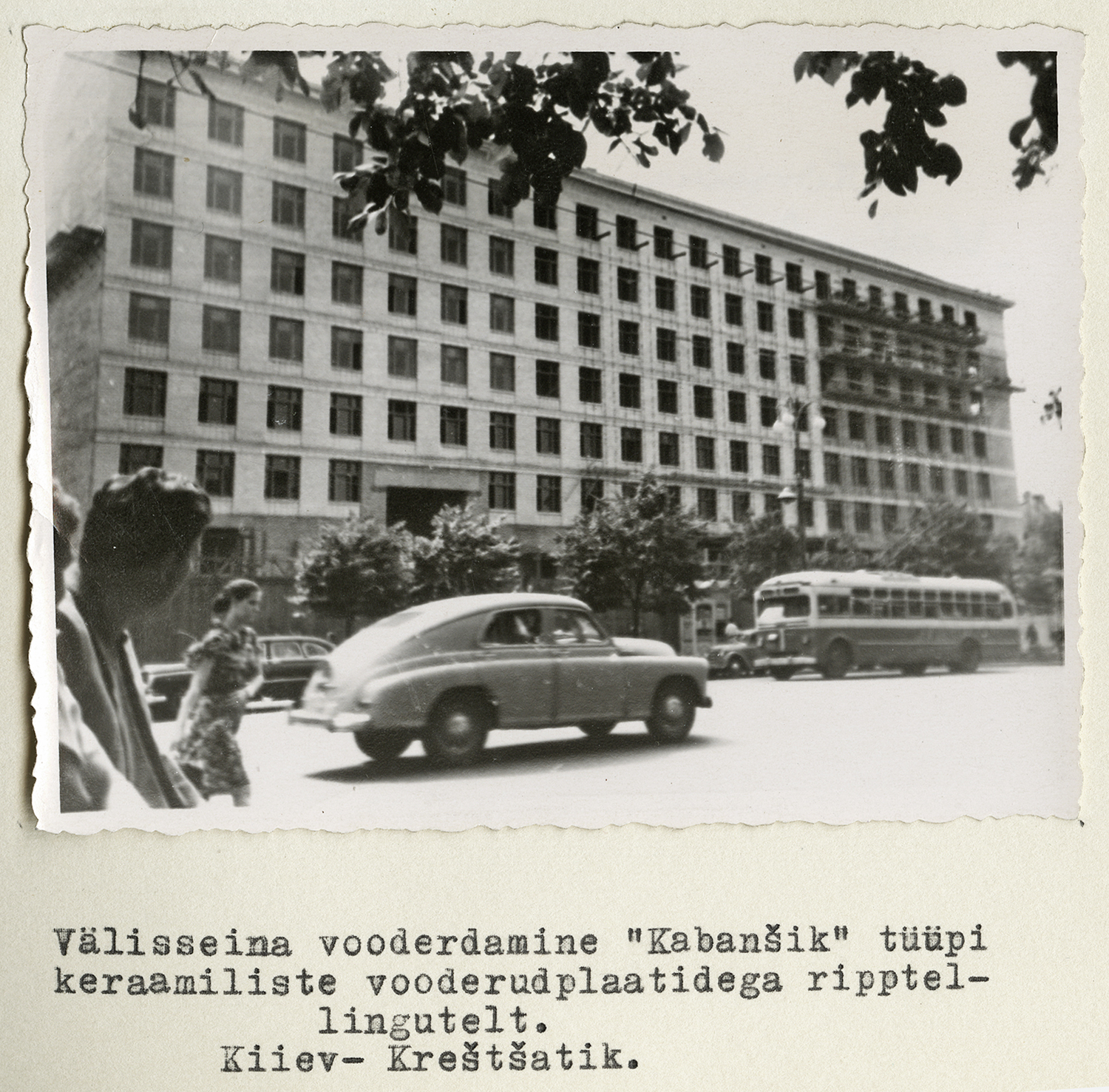

Visit to the Building Ceramics’ Factories in Kyiv

Mart Port, 1956. EAM 10.4.12

The aim of Mart Port’s creative business trip (1956) was to study whether it would be possible to increase the quality and speed of industrial construction in the field of intensified mass housing construction. During the month-long trip, he passed various cities on his way from Tallinn to Ukraine and back: Riga, Kaunas, Vilnius, Lviv, Ushgorod, Kyiv. In the report of the business trip, the architect concludes that in Latvia and Lithuania, for example, the construction methods related to the construction of mass housing are quite similar here, but the tiles used for the exterior façades, which were produced in Kyiv, deserve special attention. From there he took detailed pictures for the report. He was particularly impressed by the lining of local clay tiles of the “Kabanchyk” type, developed at the Kyiv Academy of Architecture. The “kabanchyks” were light tiles, partly hollow, which were installed on the wall using small and hanging scaffoldings. The architect already knew that in Estonia it is possible to obtain the white clay needed for its production from the Joosu quarry in Võru County. During the trip, he visited the Keramik and Keramblok ceramic tile factories and the red clay mine of the latter. The Ukrainians, who have a long tradition in the clay industry and building ceramics, also introduced him to a experimental ceramics plant under construction at the Kiev Academy of Architecture, where new prototypes used in construction were completed. In the report, he pointed out that knowledge was shared bilaterally. The builders of Kyiv, Minsk, Vilnius and Riga had got acquainted with the method of covering the walls with granite plaster used in Tallinn and praised the innovativeness of this method. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1950s

Vanalinnastuudio theatre building in Tallinn

Vilen Künnapu, Ain Padrik, 1987. EAM 41.1.16

Comedy theatre Vanalinnastuudio, which started out in Tallinn Teachers’ House, became so popular under the leadership of the legendary theatre director Eino Baskin that in the mid-1980s there was an idea of building the theatre its own house in the Old Town. The beginning of Viru Street had a plot that had long been vacant (currently the De la Gardie shopping centre, 1999) and it was considered as one possible location for the building. The theatre house was designed as a black box theatre with seats for 200 people and an attic storey for lowering decorations to the stage below. The postmodernist building was never constructed under the new political regime. The display board together with the section and view was given to the museum in 2005 by architectural historian Liivi Künnapu. In addition to that, last year the architecture office Künnapu&Padrik donated their drawings and digital archive to the museum. The lot, consisting almost 200 projects, is in the final process of adding to the musem’s collection. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1980s, architect: Ain Padrik, architect: Vilen Künnapu, Tallinn

EMA 30 / Tiny tour of models: Villa in Hiiumaa

Architect Villem Tomiste, AB Kosmos 2004. Model: Paco Ulman. EAM MK 121

A futuristic-looking villa planned in the seaside village of Õngu on the west coast of Hiiumaa. The private house is characterised by an accentuated artificiality. There are no aligned walls or ceilings parallel to the floor. Variously shaped openings cut into the fractured surfaces, offer views of the surrounding unspoilt nature. The living and dining room on the second floor of the building, designed as a single flowing space, is open to the seafront reeds, with a wedge-shaped staircase leading to it from the terrace. This private house has not been built. The model was donated to the museum in 2005. Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 2000s, architect: Villem Tomiste, EAM 30

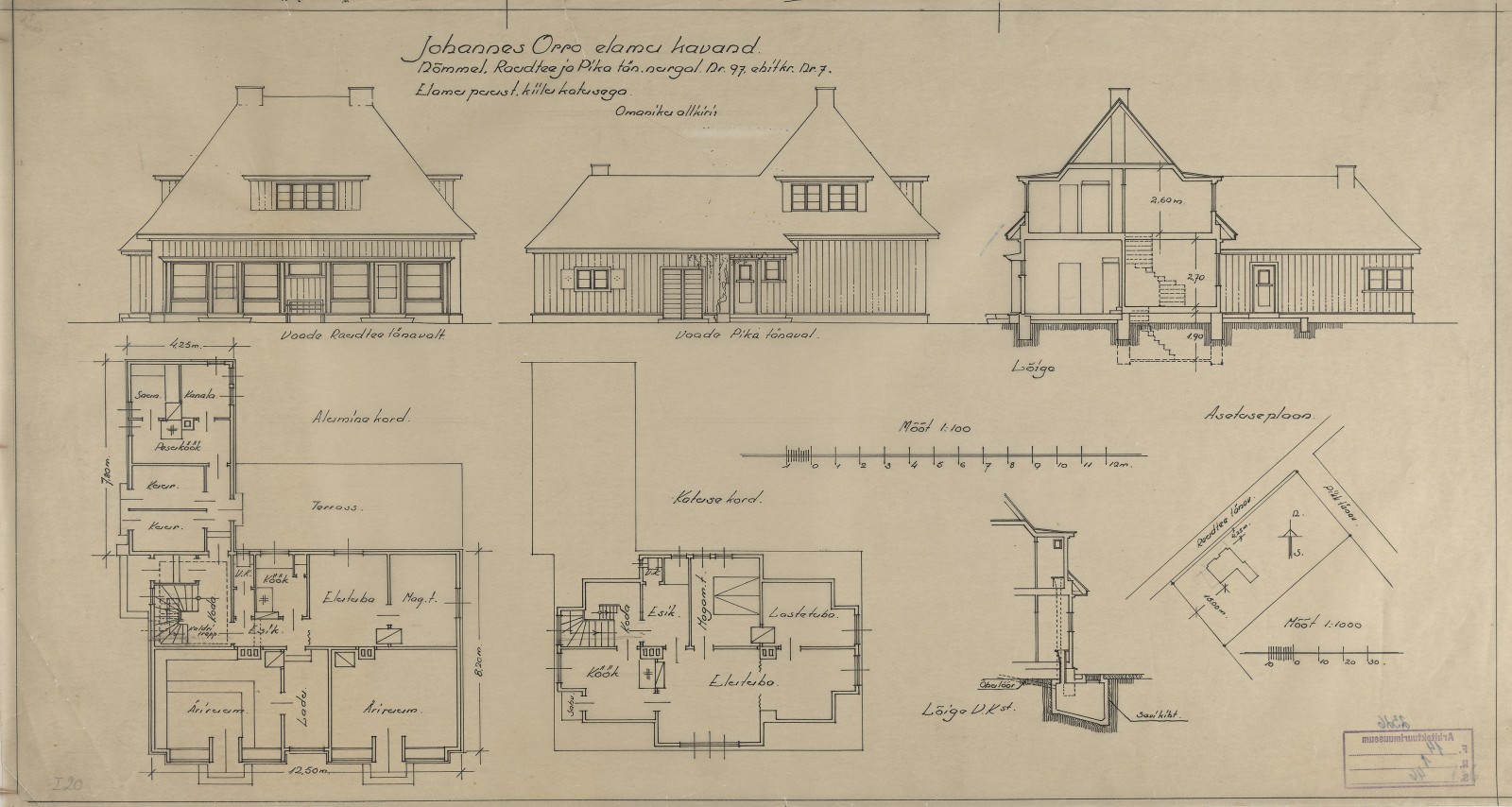

EAA 100 / Karl Tarvas

EAM 40.5

The creative legacy of Karl Tarvas (Treumann, 1885–1975) significantly shaped the residential architecture of Tallinn’s suburbs in 1920–1940. During the interwar period, he devoted himself to the less prosperous course and to improving the living conditions of the tenants by designing wooden apartment buildings to can be built quickly, the most known which is characteristic of Tallinn houses. These buildings with a timber framework with stone staircases were built by smaller entrepeneurs with a help of favorable state construction loan. The owner usually lived on the spacious apartment on the first floor of the building and rented out remaining 2-3-room apartments. In the second half of the 1930s, Karl Tarvas designed stone apartment buildings according to the state’s plan to make Tallinn’s city center more representative. In the 1920s, before founding his office, Karl Tarvas worked as an architect in Harju County and took care of the construction of rural school buildings, departments and other public buildings. His three sons also chose the profession of architect, the most known of the three is Peeter Tarvas (1916–1987). More about Karl Tarvas’ studies at the Riga Polytechnic Institute in 1906–1915 and his latest work can be read from the articly by Sandra Mälk in the collection of the Riga Technical University (RTU Scientific Journal, 2021/5): https://hesihe-journals.rtu.lv/article/view/HESIHE.2021.004/2824

Karl Tarvas was one of the 15 architects who founded the Estonian Association of Architects in 1921, which is the predecessor of the Estonian Association of Architects.

(klick on the picture to see more illustrations)

Veel: architect: Karl Tarvas, EAA 100

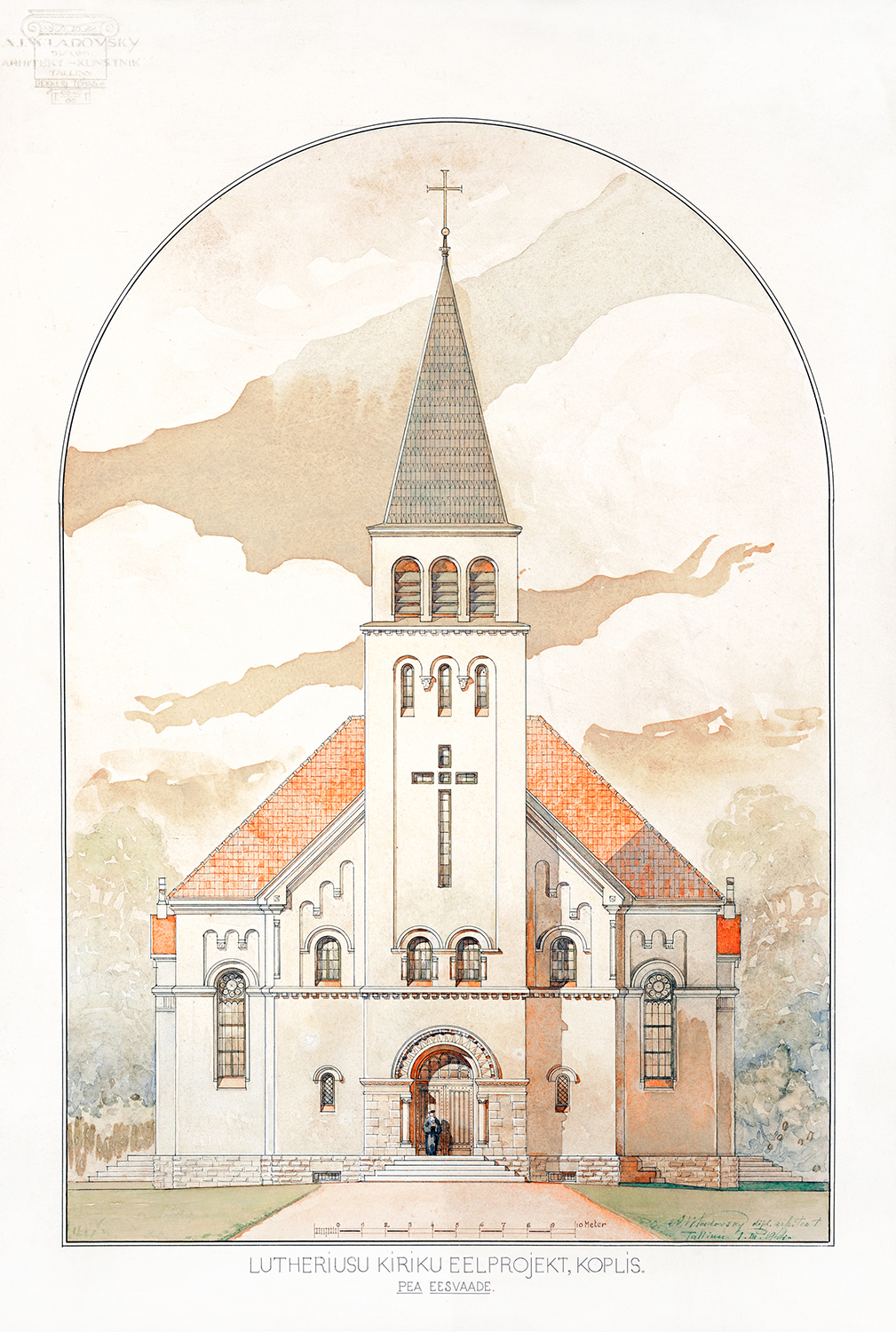

Lutheran church in Kopli, Tallinn

Aleksandr Wladovsky, 1944. EAM 3.4.56

This church is a special milestone in church architecture, as one of the last designed sacral buildings before the Soviet occupation in 1944, which denied religion on an ideological basis. The construction of the Lutheran church was planned in the Bekker settlement in the late 1930s, when the congregation rooms proved to be too small for the expanding Kopli industrial settlement. Back then the area plan for the entire city district needed to be prepared before the church building could be designed. The location of the church was to be close to the Kopli Cemetery, on the edge of a new garden suburb. The preliminary project in watercolours was donated to the museum in 2012 by Hilja Väravas. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1940s, architect: Aleksandr Wladovsky

EMA 30 / Tiny tour of models: Shopping centre for Rovaniemi

Mai Šein, 1990–1991. EAM MK 251

In 1990, Rovaniemi County organised a competition for the construction of a shopping centre and hotel complex in Rovaniemi opposite the Arktikum Science Centre across the Ounasjoki River. The centre was intended to house the county government, a hotel, shopping centre and market. The Arctic Circle and Santa Claus Village, a couple of kilometres away, were going to be marked with a special gateway. Architecture firms from Rovaniemi, Oulu and Kemi were invited to participate in the competition. The competition was won by architect Mai Šein, representing the Finnish architectural firm Poskiparta OY. Mai Šein: “I associate Lapland with mountains, so I made a large pyramid-shaped hotel and for the gate I planned a giant openwork globe, positioned above the driveway. The two polar circles were marked; the Antarctic Circle was a footpath for walking along, and the city of Rovaniemi was marked on the Arctic Circle. The adjacent area was an empty site and the participants had to make suggestions about how it could be used. I designed a square building and called it the Nabatorium. A granite wall divided the building diagonally in two – on one side was the South Pole with penguins, on the other the North Pole with polar bears.” Due to an economic downturn, the complex was never built. Mai Šein donated the model to the Estonian Museum of Architecture in 2019. Text: Anne Lass

Veel: architect: Mai Šein, EAM 30

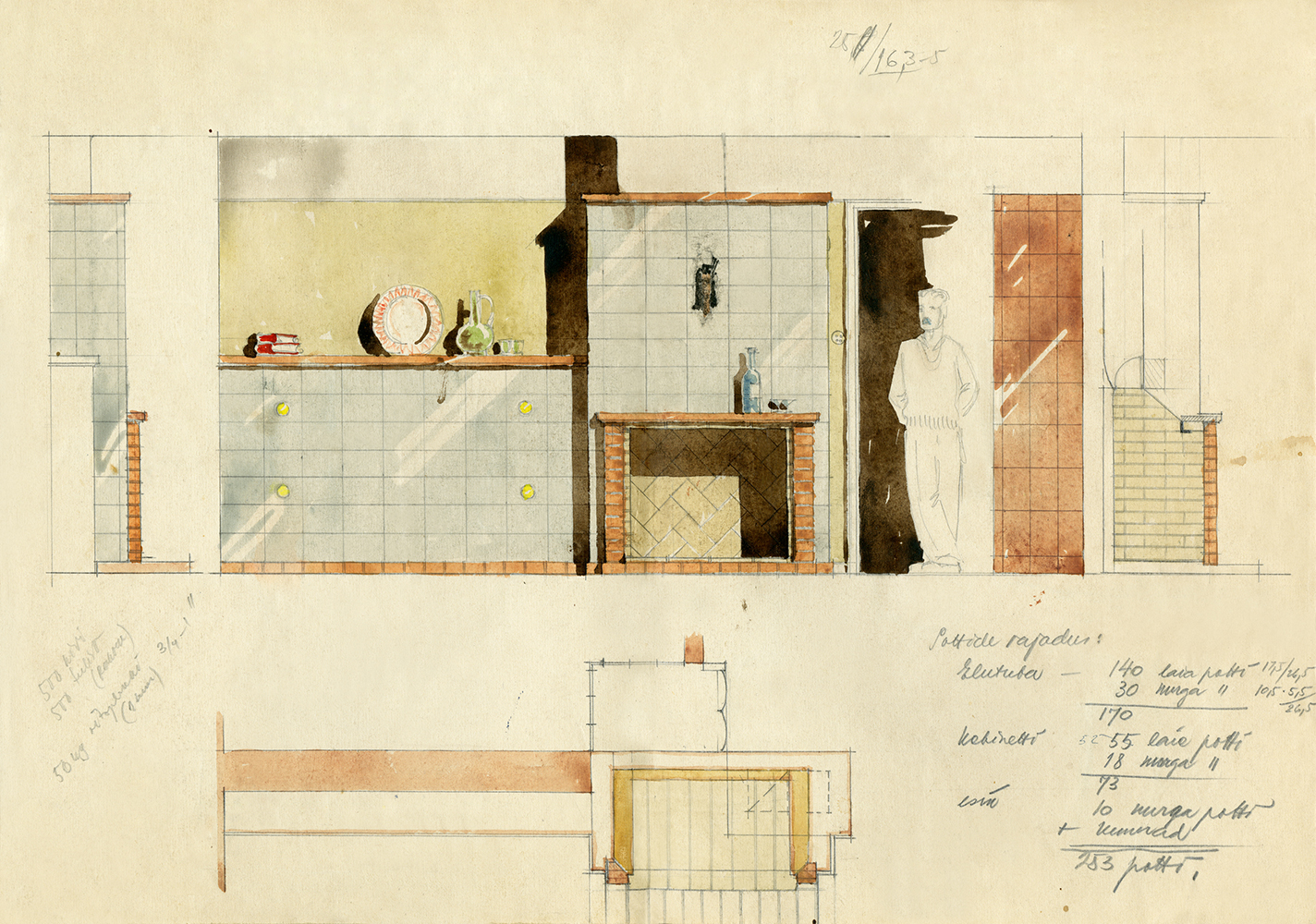

Fireplace in the architect’s house in Tallinn

Peeter Tarvas, 1946. EAM 40.1.48

Several designs of Peeter Tarvas’s cosy fireplace, in his house under construction in Maarjamäe, have been preserved. On this drawing the architect has depicted the fire chamber in the front view and from the sides, providing its cross-section from above in the bottom part of the drawing. The edges of the drawing show calculations about the number of tiles needed, revealing how many tiles are required for the living room, the hall and the private office. The architect has drawn himself standing next to the fireplace for scale. The watercoloured drawing holds now a place in Peeter Tarvas’s personal collection in the museum. The work was donated by Maria Tarvas in 2006. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1940s, architect: Peeter Tarvas

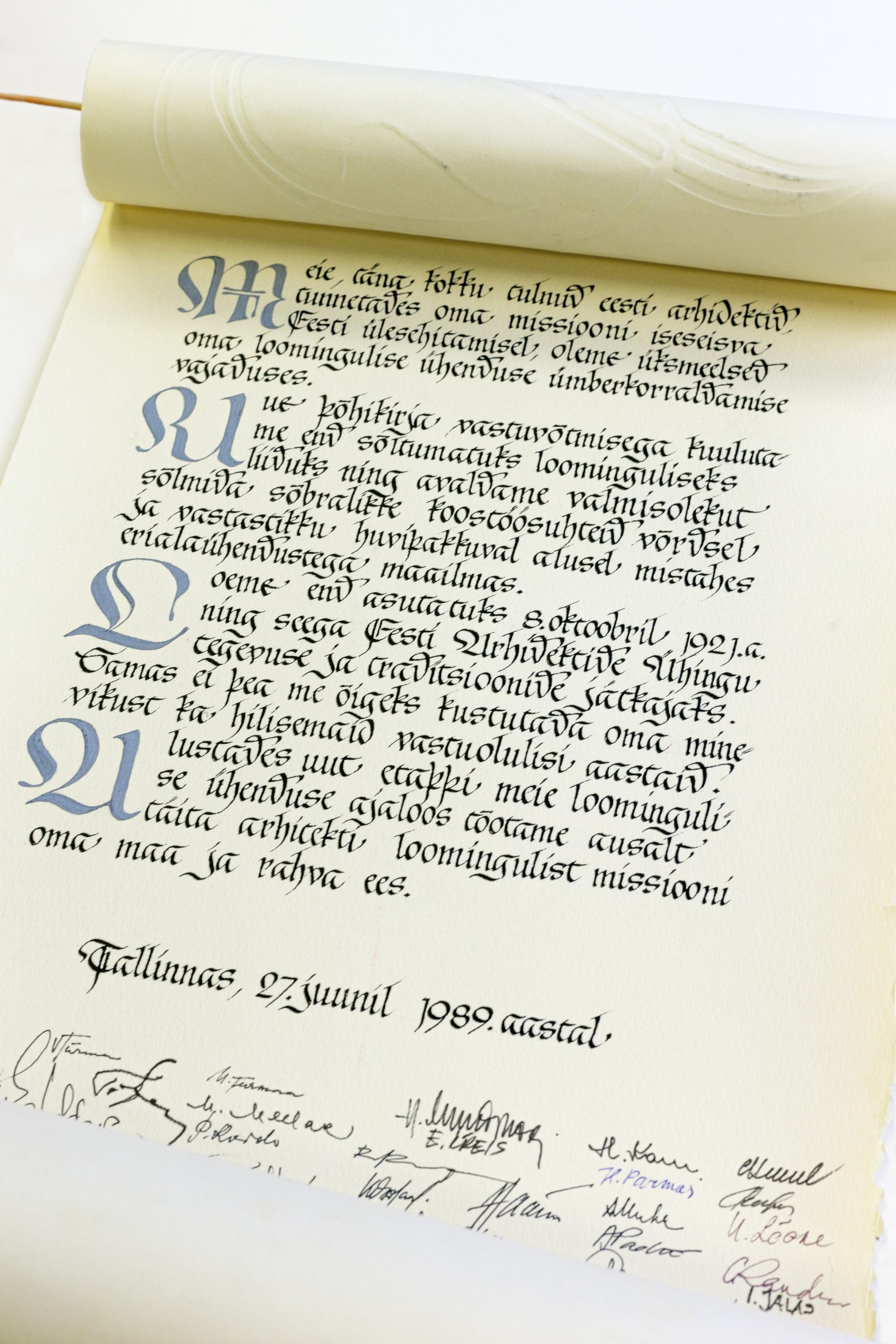

Festive document for the re-establishment of the Estonian Association of Architects

Document of the EEA,1989. EAM 10.4.9

The Estonian Association of Architects was the first of the creative associations to strive for independence in the late 1980s and to break away from the all-union USSR Union of Architects. The first groundbreaking decision was taken one day in November 1987, when a meeting was held to discuss the association’s activities. The architects decided that from now on the beginning date of the creative union should no longer be known as 1944, but the day of the establishment of the Estonian Union of Architects on October 8, 1921. The following year, by the initiative of architect Leonhard Lapin, the union decided to continue as an independent association. For this, a ceremonial document was drawn up in 27 June 1989. This beautiful document with a calligraphic text and the signatures of the architects made it possible to summon the official charter that was registered in November 1989. By this general assembly of the EEA selected the first board and architect Ike Volkov as the first chairman of the association. The master of the leatherwork that holds the paper document together is Aime Pralla. The EEA gave the document to the museum for the safekeeping in 1998. Text: Sandra Mälk (click on the image to see more photos)

Veel: 1980s

EAM 30 / Tiny tour of models: Tallinn harbour grain elevator

Anton Klevchshinsky, Feodor Yenakiyev, 1892–1893. Scale model: J. Kangro, K. Asik (woodwork), Krasimoshev, O. Sakker (metalwork), 1899. EAM MK 61

In 1893, a huge 6-storey limestone grain elevator with a 30-metre tower was completed on Viktoria quay at the harbour in Tallinn. At the time it was one of the largest and most modern in tsarist Russia, holding more than 3,000 tons of grain that could be mechanically loaded directly from wagons to ships. The elevator was designed by architect and academic Anton Klevchshinsky and engineer Feodor Yenakiyev, both from St Petersburg. A model of the building was completed in 1899 and was shown a year later at the 1900 Paris Exposition. The model is extremely detailed, there are various mechanisms in the interior that were originally able to move. The scale model’s journey to the Museum of Estonian Architecture has been a long one. After the exposition in Paris it was given to the Museum of the Ministry of Transport in St Petersburg. In 1971, the model came to Estonia and for 30 years was on display at the Railway Museum in the main building of Baltic Station. From there it found its way to the Estonian History Museum which, in 2000, donated the model to the Estonian Museum of Architecture. The model was restored by Kanut restorers. Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1890s, architect: Anton Klevchshinsky, EAM 30

EMA 30 / Tiny tour of models: Estonian Agricultural Academy (currently Estonian University of Life Sciences) in Tartu

Valve Pormeister, 1979. EAM MK 248

The construction of the new building complex for the Estonian Agricultural Academy in Tähtvere at the north-western border of Tartu was already launched in the 1960s. The Faculty of Forestry and Agricultural Mechanics building, designed by architect Valve Pormeister, was completed in 1983. This was one of the largest new buildings in Tartu, and the one with the most complex layout. The building consists of two contrasting structures intersected by three trapezium-shaped courtyards. The stepped main facade is articulated by round windowless stairwell towers, while the part of the building facing the river has a more laconic design. The massive circular auditorium was never built. The model was handed to the museum by the Estonian University of Life Sciences in 2019. Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1970s, Tartu

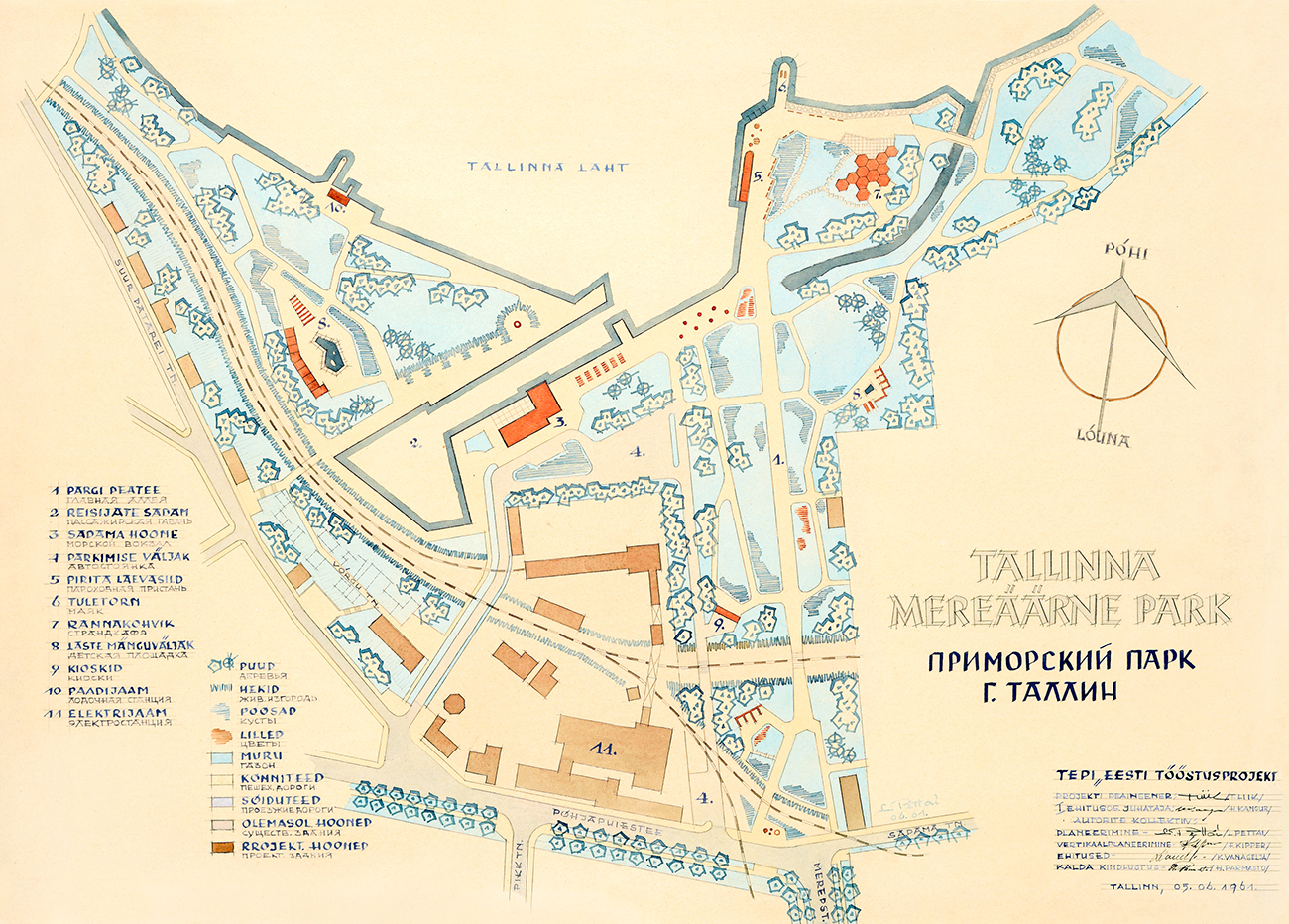

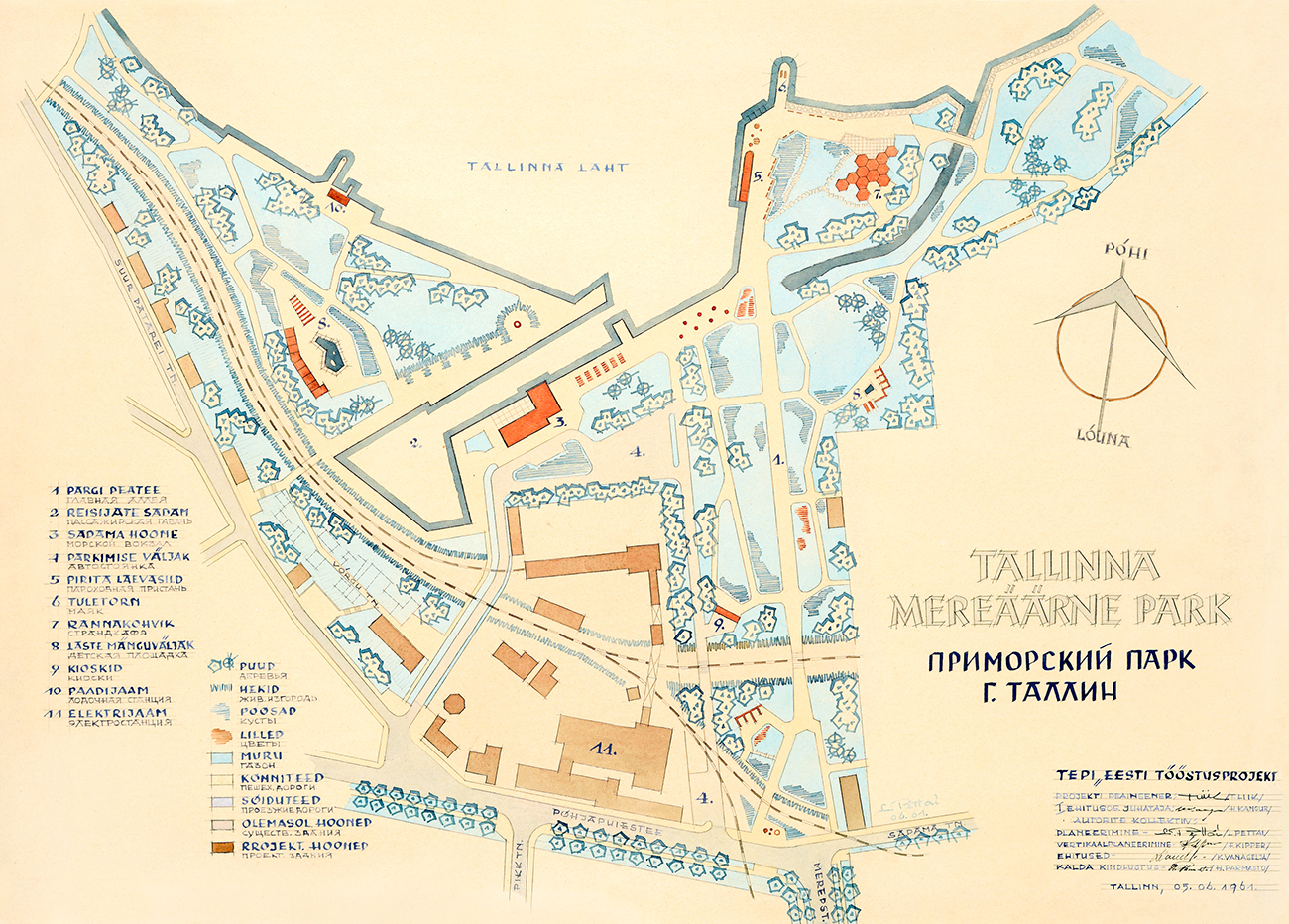

Seaside park in Tallinn

Lidia Pettai, 1961. EAM 15.4.150

60 years ago, the opening of the Tallinn sea border was under discussion with the intention of turning it into a green area with port facilities. Back then, In the 1960s, and primarily at Finland’s initiative, plans were made to clear up all the areas surrounding the port with regard to the reopening of the Tallinn-Helsinki seaway and the construction of the passenger port. The seaside area – in the immediate proximity of Old Town – was partly in the military zone and opening it up to the city became a lively issue. Although, only a handful of buildings were fixed up during the Soviet era. New buildings were due to be constructed in the densely built-up industrial area together with the main park road that was in the direction of Mere Boulevard (No. 1), such as the beach café (7), the port building (3) and children’s playgrounds (8). A team of architects worked with the design at the Eesti Tööstusprojekt. Kalju Vanaselja designed the buildings and H. Parmasto behind the schemes of coastal reinforcements. The plan was designed by architect Lidia Pettai, whose watercoloured work was given to the museum in 2012 by Reet Priilaht. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1960s, architect: Lidia Pettai, Tallinn

EMA 30 / Tiny tour of models: Estonian Pavilion at Expo 2015 Milan

Kadarik Tüür Architects, 2013–2015. Model: Martin Kaares, 2014. EAM MK 255

The World Expo in Milan, opened in May 2015, was the second time Estonia had its own pavilion at a world’s fair. In 2013, the pavilion design competition was won by Kadarik Tüür Arhitektid. The jury praised the pavilion’s light and airy solution, playfulness and flexible modular system. The pavilion was formed from wood-covered modules reminiscent of nesting boxes, stacked in a staggered fashion. The two floors of the pavilion featured interactive video installations about Estonian nature, life and culture, while entrepreneurs presented their products and services. The third level, partly open to the sky, was a pleasant place to spend time, and was filled plants from Estonia. Two kiiking swings were erected in front of the main entrance. These and the 34 energy-generating swings between the nest boxes proved to be the pavilion’s most popular attractions. In six months, 3.4 million people visited the Estonian pavilion and it won a bronze medal for the design of the exhibition in a category of the pavilions under 2000 m2 (by the creative agency IDEA and the production company RGB Baltic).

The model of the pavilion was donated to the museum by the Estonian representation at the 2020 Expo Dubai.

Text: Anne Lass. Photos: Liisi Anvelt

Veel: 2010s, architect: Mihkel Tüür, architect: Ott Kadarik

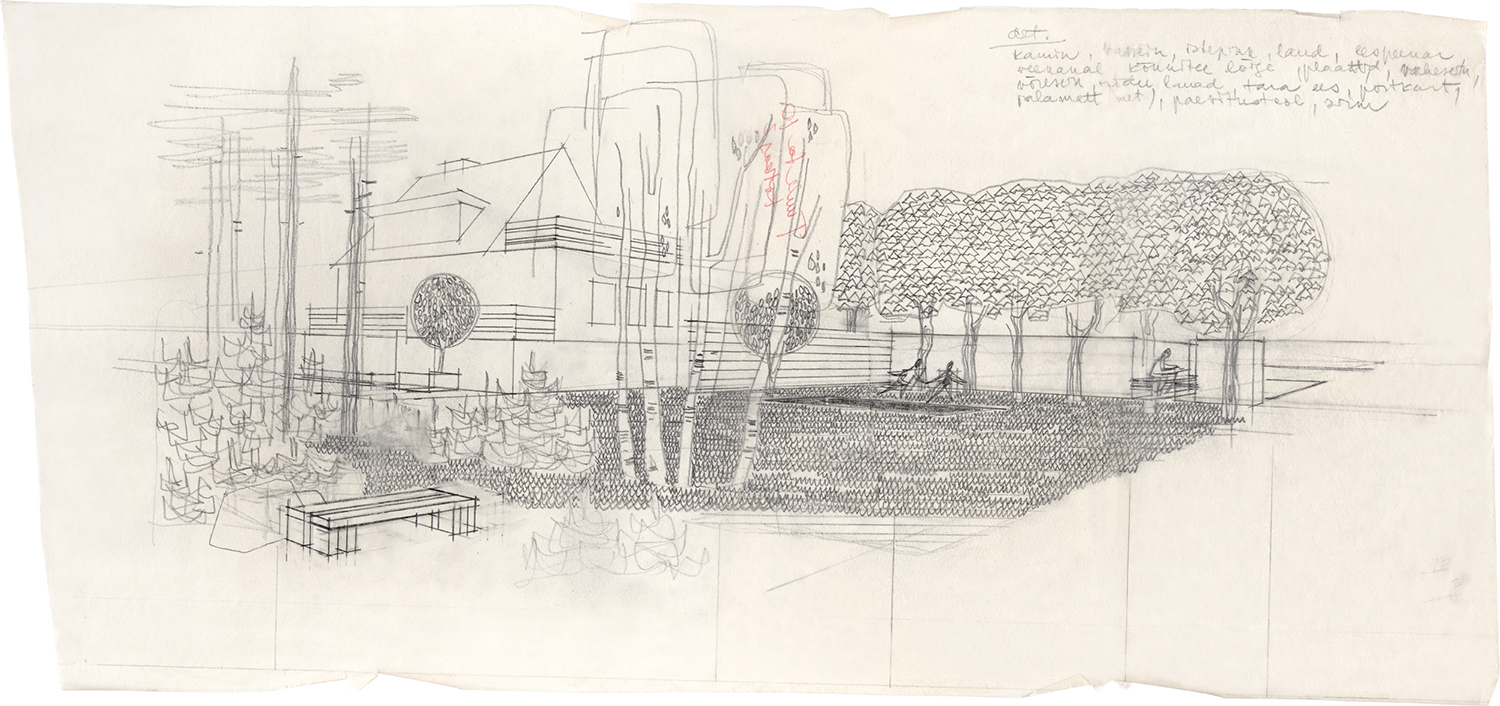

Garden planning and landscaping sketch

Vaike Parker, 1971. EAM 45.1.8

The house located in Merivälja district in Tallinn was acquired by the Association of Journalists in the 1960s and soon transformed into the institution’s holiday home. A thorough design for the garden of the house was needed to organise bigger events. It was commissioned from the renowned landscape architect Vaike Parker. The sketch depicts architect’s first thoughts before drawing up a complete design – these thoughts have been sketched on delicate tracing paper using a soft pencil. Listed are the objects that complement the landscaping details, e.g. a water canal, a deck chair and a screen. In 2010, Vaike Parker

Veel: 1970s, landscape architect: Vaike Parker, landscape architecture

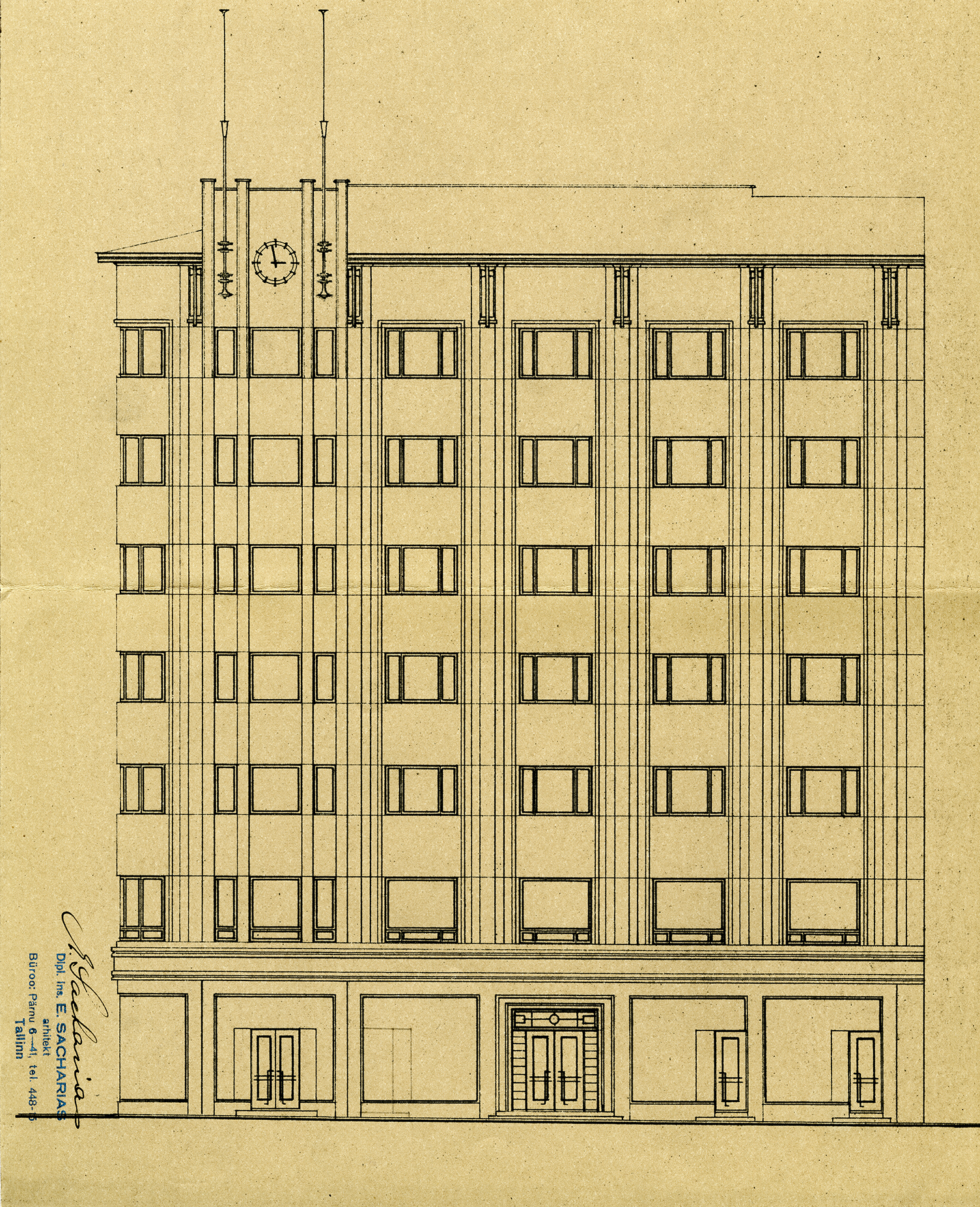

Office and Residential Building at Pärnu Road

Eugen Sacharias, 1936. EAM 2.2.320

The seven-storey building on the corner of Pärnu Road and Väike-Karja Street is one of the most representative rental houses built in the second half of the 1930s in the center of Tallinn. The project was commissioned from Eugen Sacharias (1906–2002) by the association “Elamu”. On the ground floor there were and still are business premises, on the first floor offices and on the higher floors there were multi-room apartments with all amenities, bathrooms and maid’s rooms. As there were several doctors among the tenants at that time, this house has also been called the so-called doctors’ house. On the seventh floor of the building were the offices of the architect Sacharias.

The Baltic-German architect Eugen Sacharias was born on April 21, 1906, who studied at the Technical University of Prague in 1925–1931. As a talented and enterprising young architect, he first helped Eugen Habermann design the so-called Urla House on 10 Pärnu Road, after which he founded his own office. In the following ten years almost 40 apartment building projects were completed. That shaped the representative visual of Tallinn as the capital. In 1941, Sacharias left to Germany with his family and ended up in Australia, where he continued to work as an architect in a construction company. In April 1991, Eugen Sacharias’ 85th birthday was celebrated with an exhibition in the lobby of the Library of the Academy of Sciences (now the Tallinn University Library). The exhibition was curated by art historian Mart Kalm. This was the first exhibition of the Estonian Museum of Architecture, founded three months earlier.

Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1930s, architect: Eugen Sacharias, Tallinn

EMA 30 / Tiny tour of models: Extension to Tallinn Secondary School of Science

Marika Lõoke, 1981. MK 227

Tallinn Secondary School of Science (Tallinna Reaalkool) will be 140 years old this year. The school was founded in 1881, in the same year an all-Russian architectural competition was organized to obtain a schoolhouse project. The competition was won by Max Hoeppener (1848–1924), a Baltic German architect from Moscow. Hoeppener was assisted in the construction project by Carl Gustav Jacoby, a Tallinn city engineer at the time. The first building designed for a school building in Tallinn was completed in 1884.

A century later, in 1981, a competition was held for a vision of the extension of the school building. The location of the new addition was to be set on the current sports field. 13 works came to the competition. The first prize was given to the architects Vilen Künnapu and Ain Padrik for the project named “Kivirünta” (EAM 41.1.10), the second place went to Kullervo Kliimand’s work “Poiss” (“A Boy”). The third prize was shared by Kiira Soosaar, Siiri Kasemets and Jüri Karu’s competition work “Imelik” (“Strange”) and “Koolimaja” (“School House) by Marika Lõoke. In the magazine Ehituskunst, the editor of the magazine, architect Ado Eigi, describes it as follows: “ In addition to the attractively playful, postmodernist façades maintained at a good professional level and the expressive plan solution, the competition work “Koolimaja” (author Marika Lõoke) also suggested an interesting corner solution together with the M. Gorky named Library building (now Tallinn Central Library – A.L.).” A year later Marika Lõoke also received the 3rd prize at the competition for the new building of the Kreutzwald State Library. The library competition model belonging to the collection of the Museum of Architecture can be seen in the soon-to-open exhibition at the National Library. Together with several other models, the author donated them to the museum in 2017. See also “Architecture. Second-third, 1982–1983.” Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1980s, architect: Marika Lõoke, Tallinn

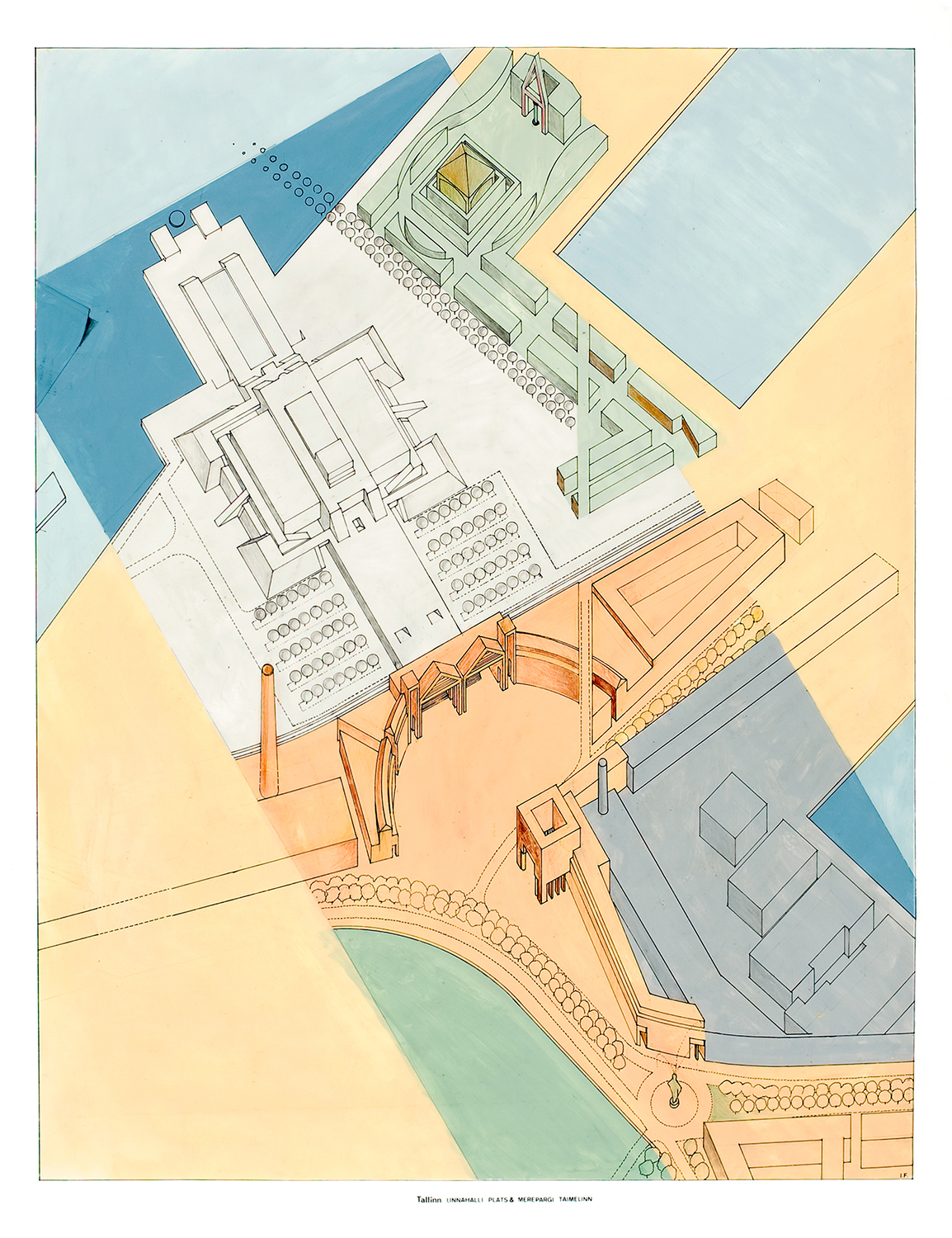

Linnahall Square and the Merepargi Taimelinn (the Plant City of the Sea Park)

Ignar Fjuk, 1982. EAM 5.4.61

Tallinn Linnahall was built during the building frenzy which preceded the 1980 Olympics, but the surroundings were not developed as planned. The area between the power station and the commercial port was cleaned of the production residue from the factories and the concrete blocks that were laying around. At the same time, discussions became louder about granting people in the city access to the coastal zone, which had thus far belonged to the border zone and been managed by large factories. Ignar Fjuk designed a green park area to surround the Linnahall, which also included a place for architectural forms – gates and pavilions. He presented his vision in the group exhibition ofthe Tallinn School, which took place at the Tallinn Art Salon in 1983. This illustration made in ink and gouache was given to the museum as a gift by the author in 2002. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1980s, architect: Ignar Fjuk, Tallinn

Kellomäki Motif

Paul Mielberg, 1913. EAM K 37

Paul Mielberg, architect and lecturer at the University of Tartu 1922–1940, was born on March 18, 1881 in Tbilisi (Georgia). His father, Johannes Mielberg from Viljandi County, was the director of the Physics Observatory in Tbilisi. From 1899 to 1901, Paul Mielberg studied at the Riga Polytechnic Institute, afterwards at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, where he received a diploma of Artist-Architect in 1910. After graduating, Mielberg worked for several well-known St. Petersburg architects. From 1911 to 1918, he was the chief architect of the Swedish architect Fredrik Lidval (Karl Burman also worked as Lidval’s assistant a few years before), participating in the design and construction of St. Petersburg Art Nouveau landmarks such as the Azov-Don Bank and Count Tolstoy’s tenement house. In 1922, Mielberg came to Tartu and became an associate professor of construction studies at the University of Tartu and also an architect of the university. More than a dozen buildings belonging to the university were built or reconstructed according to his design or supervision. On December 18, 1996, art historian Andres Kurg wrote a review article about Paul Mielberg’s role as an architect of the university in Postimees “About the Architect who designed the university and the Tähtvere district”.

Paul Mielberg left Estonia in 1941 and died in 1942 in Germany.

In 2010, the architect’s daughter Olga Kompus donated her father’s watercolors from 1911–1913 to the museum. Kellomäki, a popular summer resort and excursion destination in Karelia on the Gulf of Finland, about 40 km from St. Petersburg, is a sketchy romantic landscape with Art Nouveau handwriting. For moody views of the Kellomäki, see the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ACNcIEXRIM

Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1910s, architect: Paul Mielberg, Tartu

EMA 30 / Tiny tour of models: Cultural Centre in Paide

The model of the Cultural Centre in Paide, 1986. EAM MK 91

The Paide Cultural Centre was designed in the Estonian Rural Construction Project in 1984–85. The architect Hans Kõll and the designer Rein Üts are the authors of the project. The stained glass window of the façade was designed by the artist Kaarel Kurismaa. The unique interiors of the cultural centre are the work of interior architects Tiiu Pai and Taimi Rõugu, stained glass windows are designed by the artist Kalev Roomet. The representative building on the corner of Pärnu and Tööstuse streets – where the new social center of Paide was to come – was completed on 1987. On January 1, 1988, the magazine “Sirp and Vasar” (The Hammer and the Sickle) published photos of the new culture house on the front page and wrote:

“The dream of the people of Järva County has come true – on December 27, the cultural house of Paide district was opened. The biggest in Estonia, the best in Estonia. Quickly and well-built, given to the customer half a year before the deadline – this should be the perestroika momentum for other constructions as well, especially for cultural objects.”

Despite this and the building being criticized at the time for its scalability and restless façade design it was named the best building of 1988. The Paide Cultural Centre (now the Paide Music and Theater House) has so far functioned in its original use and preserved its authentic appearance and interiors. In 2016, the building was declared as a cultural monument. The 1:100 model of the Paide Cultural Centre was made by Rein Koster and Ants Anari, it was added to the museum’s collection in 2001. Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1980ndad, 1980s, architect: Hans Kõll, Paide

Riga Estonian Students’ Society

Riga Estonian Students' Society, 1909. EAM.16.4.71

The Riga Polytechnic Institute became one of the most important providers of technical education in the 19th and 20th centuries, where well-known Estonian architects, engineers, industrialists and others studied. At that time, it was one of the closest schools for studying architecture next to the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. The Tallinn Technical School (Tallinna Tehnikum) was established not until 1918. By the new century, there were already many Estonian students at the Riga Polytechnic Institute that several corporations were formed to unite the students. The picture probably shows the founders of the Riga Estonian Students’ Society (later the Student Society Liivika), which was formed in 1909. These young students are future architects, engineers and industrialists who have greatly influenced Estonian society. According to their educational background, they were later called “riialased”, the Rigans.

Sitting Left to the Right: architect Anton Soans, Anton Uesson – the later mayor of Tallinn and Karl Treumann (Tarvas). Standing Left to the Right: Karl Feldmann (?), Architect Aleksander Bürger, banker Heinrich Väljamäe, engineer Konstantin Zeren, lawyer Voldemar Tomson, Peeter Sisask (?). The photo was purchased from an antique shop in 2020. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1900s, architect: Anton Uesson, architect: Karl Tarvas

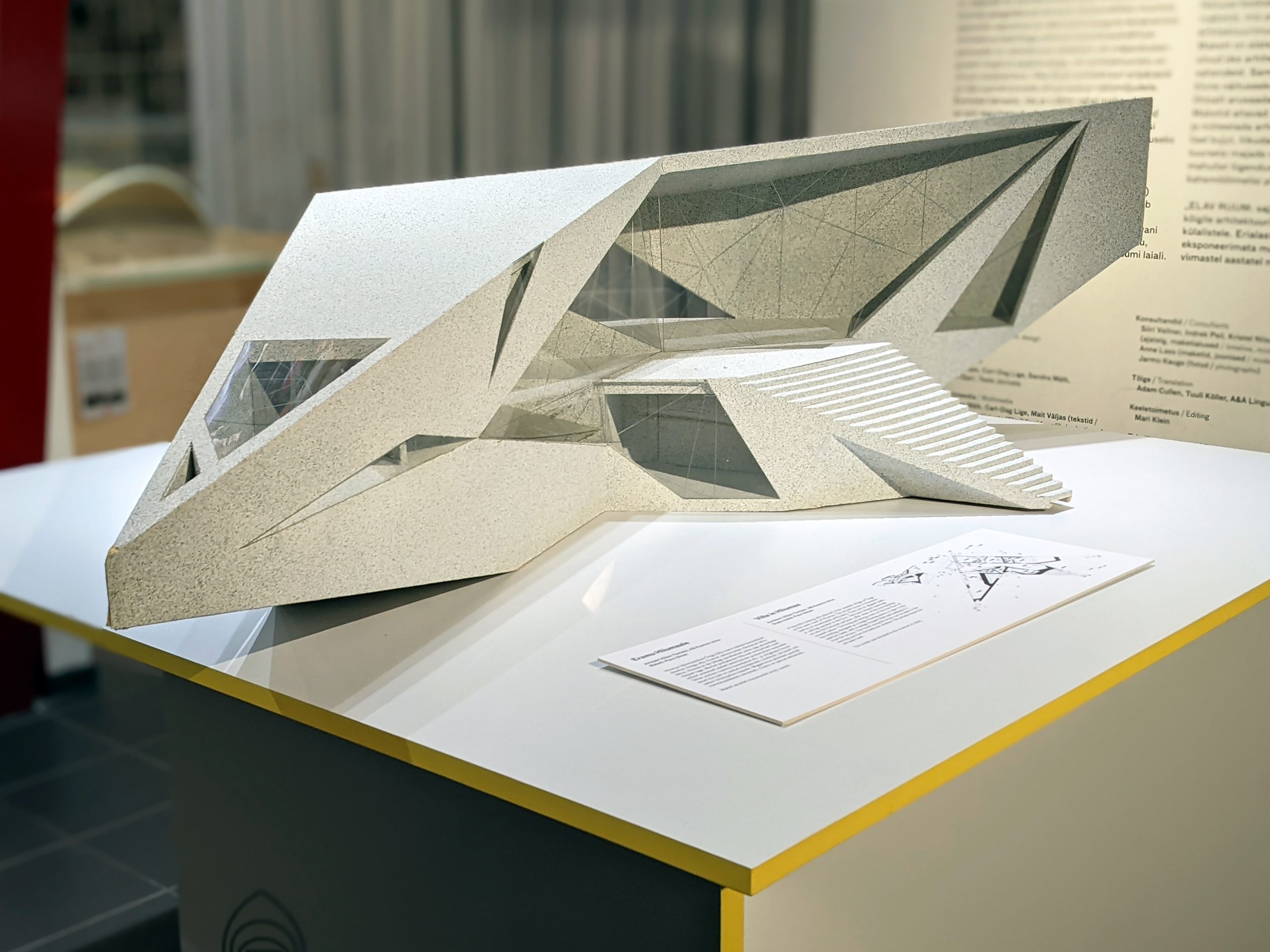

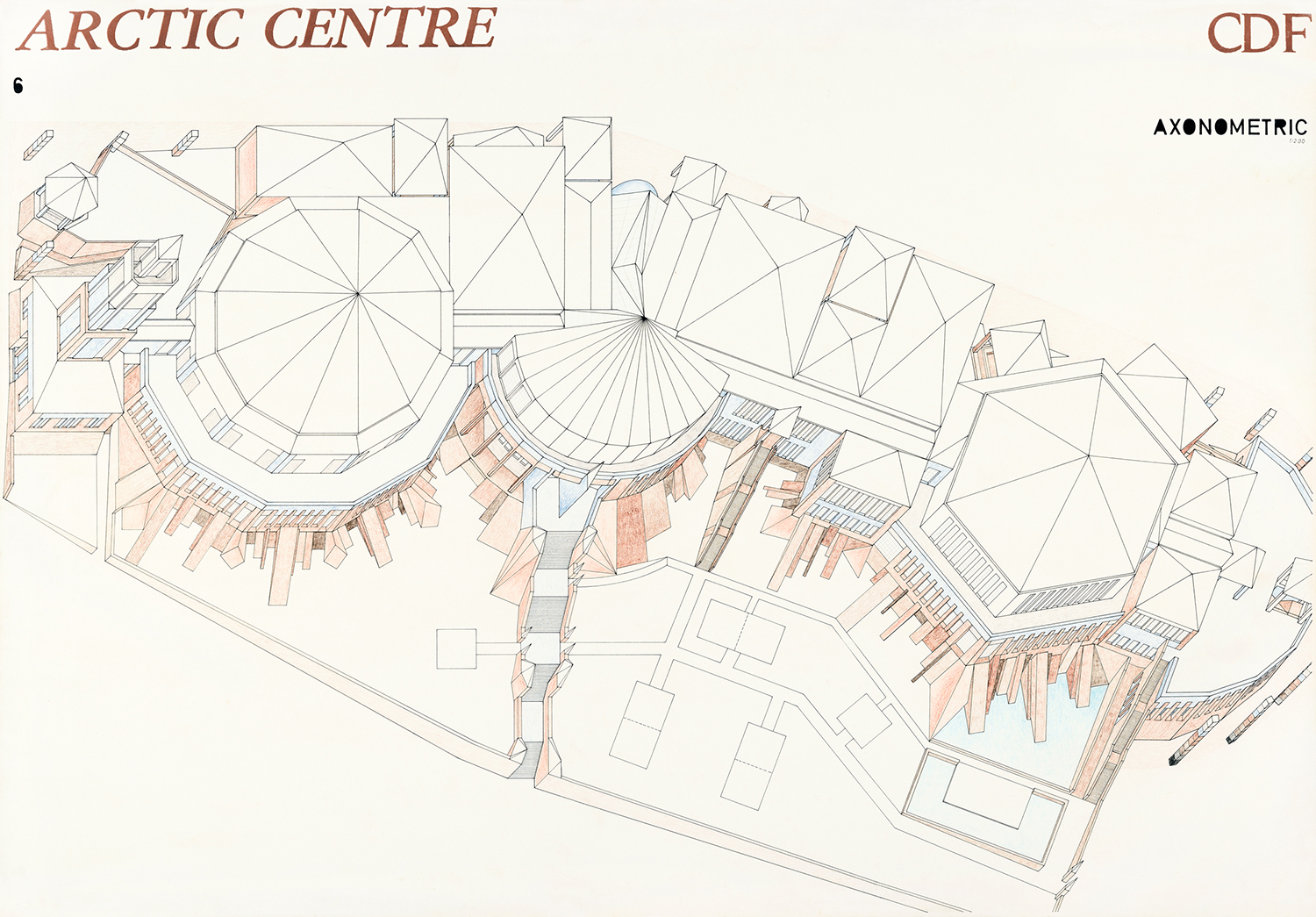

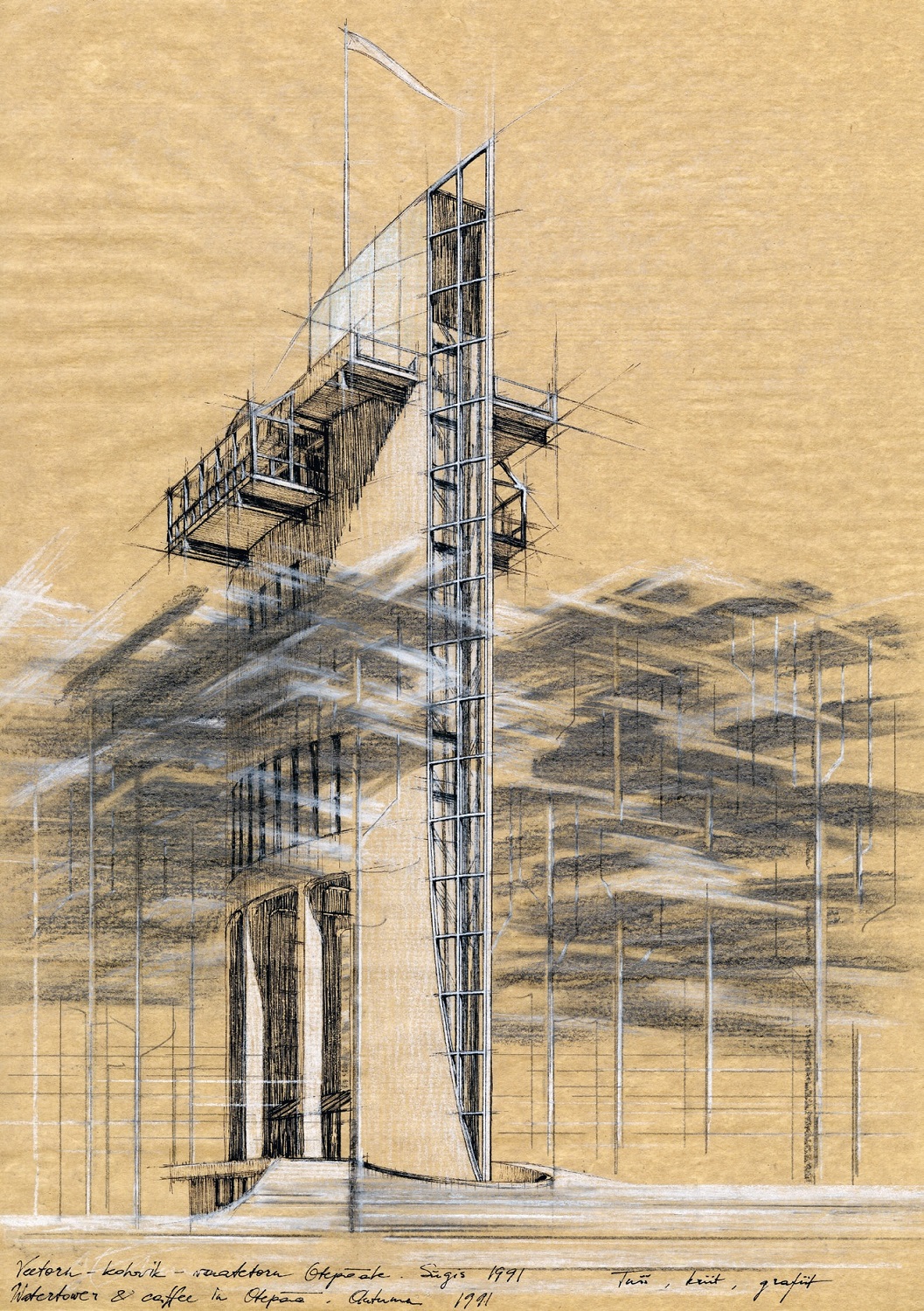

Competition entry for the Arctic Centre in Rovaniemi

Andres Alver, Leonhard Lapin, 1982. EAM.5.4.70

Eight countries in the northern hemisphere, including the Soviet Union with three entries from Estonia, took part in the international architectural competition the purpose of which was to introduce Arctic nature, history and culture. The designers for the entry “CDF” drew inspiration from Caspar David Friedrich’s painting The Sea of Ice. The shape of the building, which houses two different museums – the Arctic Museum and the Provincial Museum of Lapland – bears direct resemblance to ridged ice. The idea of being dominated by Nordic nature is further emphasised by the complex being situated on the steep riverbank that follows the natural relief of the plot. Nine large-format drawings altogether with the axonometric projection shown here were brought to the museum by the authors in 2008. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1980ndad, 1980s, architect: Andres Alver, architect: Leonhard Lapin, architectural competition

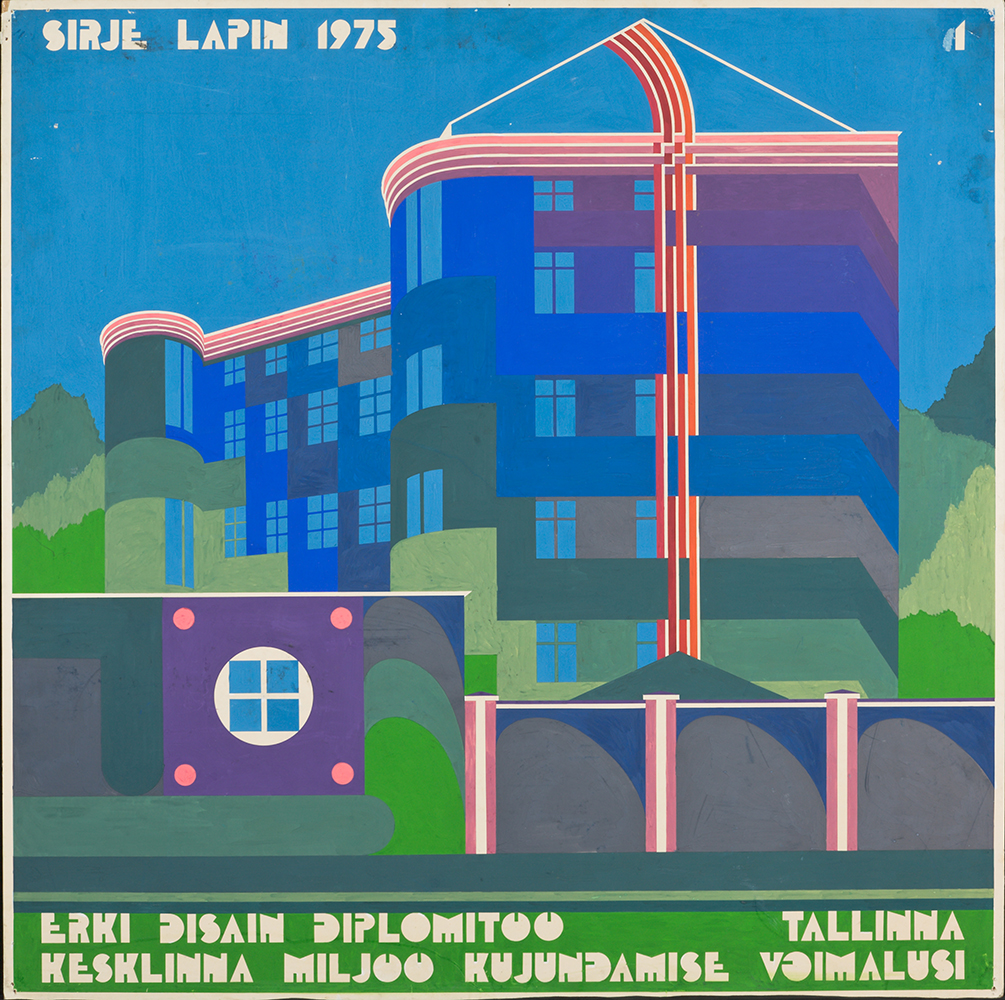

A new environment of Tallinn

Sirje Runge, 1975. EAM 4.17.1

The images show different visions for enlivening the urban space of Tallinn. Designer Sirje Runge (Lapin 1969–82) submitted this design as her diploma work at the Estonian State Art Institute. The goal was to propose new ideas to bring citizens and contemporary city closer together in an artistic manner by integrating new technical landscape forms into the urban space. Upgrading the monotonous city became an unlimited field of work for young creatives against the backdrop of the official Soviet architecture that favoured repetitive environments. In her vision, new elements were introduced to the city and the colour schemes added to the housing. The visions were of three types: the first (p. 1 and 2), supergraphics for the façades; secondly, audiovisual communication centres – the artist saw in those open and accessible spaces a new meeting places for the community and where advertisement also plays its role. The latter (p. 8 and 9) introduced conceptual objects such as steel box that governs a natural object and a clock mechanism situated at the main square in Tallinn. In that sense, such irrational objects placed in the industrial city would bring human and city closer together. Sirje Runge gave the works to the museum as a gift in 2003. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1970s, designer: Sirje Runge, Tallinn

Pavilion at Nigula bog

Ethel Brafmann, 1964. EAM 35.1.105

The pavilion is located close to the Latvian border in Pärnu County in Nigula Nature Reserve, which was established in 1957. Ethel Brafmann, a young and promising landscape architect at the time, made the design for the pavilion on the territory of the nature reserve. The purpose of the pavilion is to allow travellers to rest and prepare food while in the middle of a display dedicated to the nature reserve. The wooden pavilion is equipped with a stove and consists of a single 27 m2 room, a kitchen and a small hall with windows with shutters. The drawings originated from the collections that were donated to the museum at 2006 by Inga Tõnissar. Text: Sandra Mälk

(klick on the image to see more pictures)

Veel: 1960s, landscape architect: Ethel Brafmann

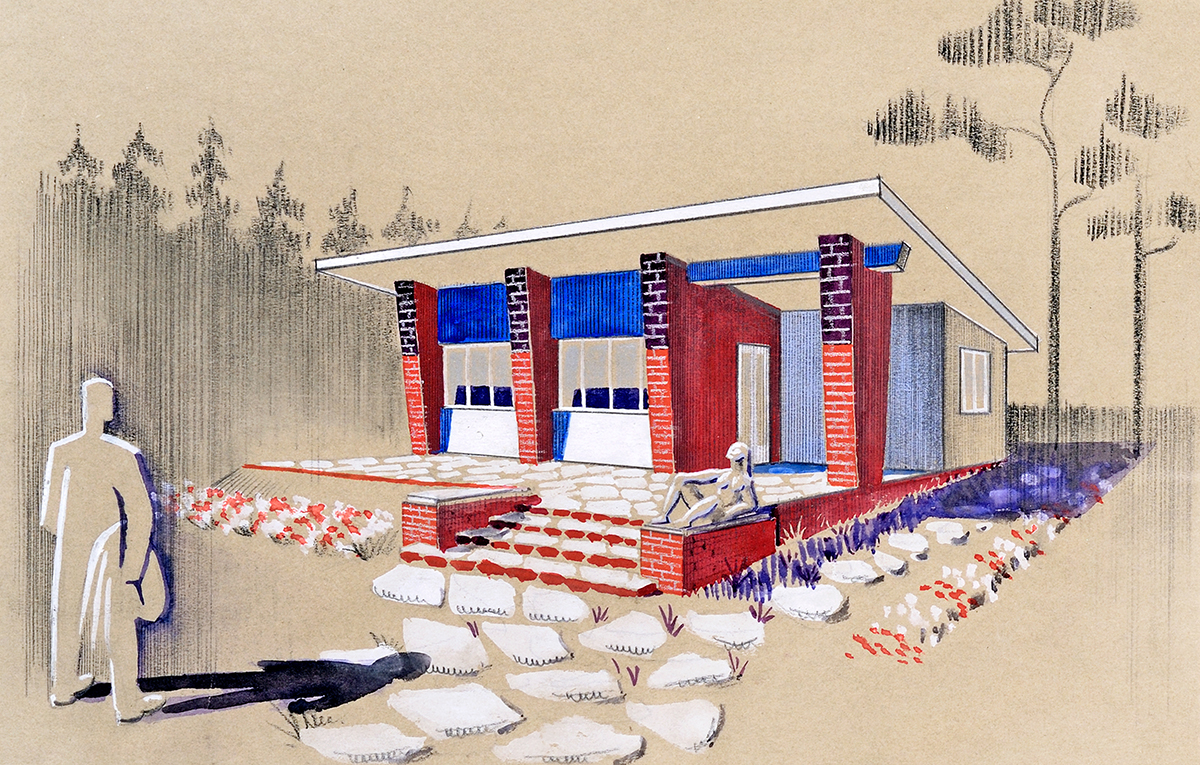

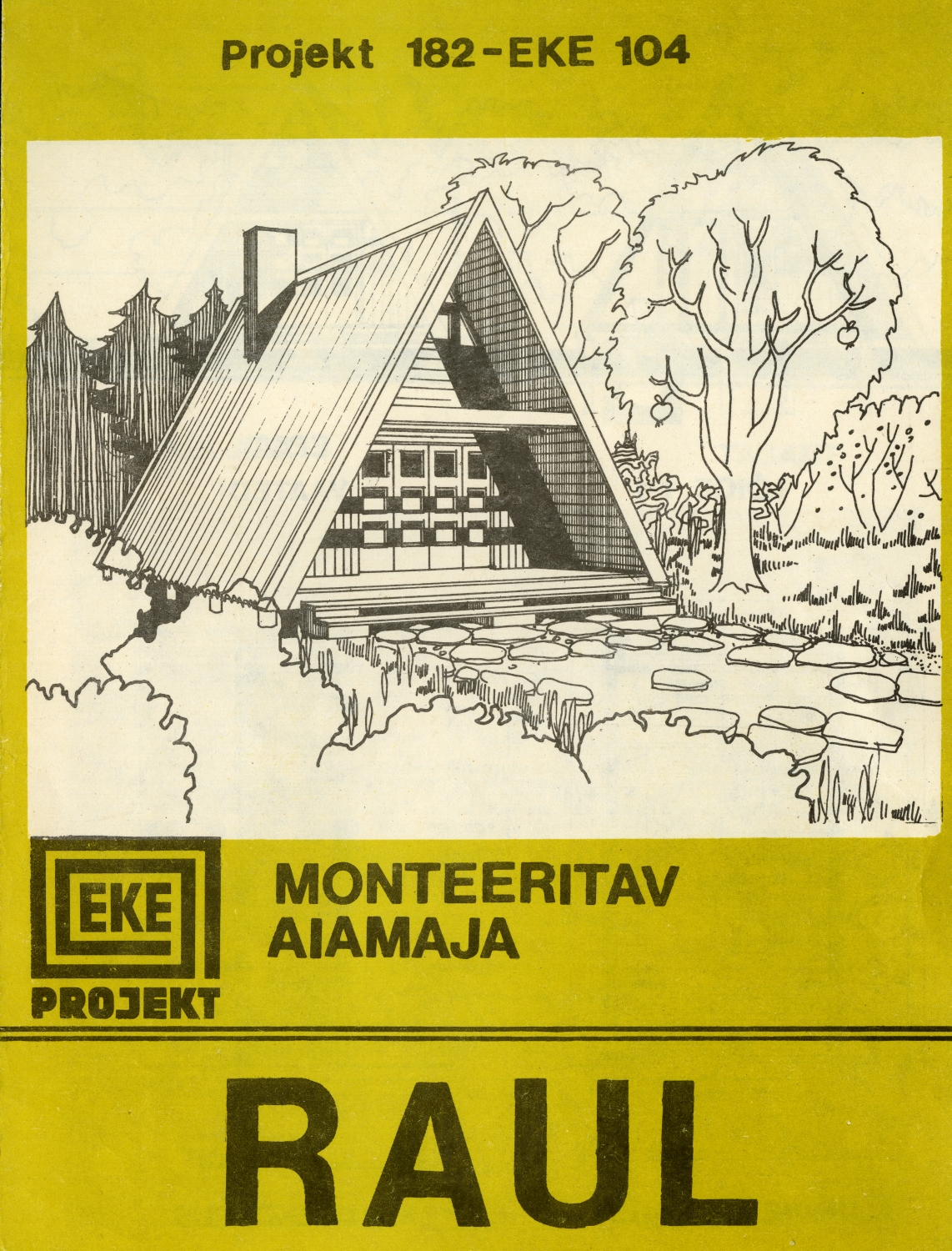

Weekend house project

Mart Port, 1946 EAM 52.1.8